Margaret Thatcher: Facts about the controversial prime minister in 'The Crown'

The "Iron Lady" remains one of Britain's most divisive political figures.

More than 30 years since she was last in power, Margaret Thatcher remains a divisive figure in Britain. Some see the prime minister as having saved the country from economic decline, while others believe she destroyed the livelihoods of millions of workers. But none can deny that Thatcher became a legend in her own lifetime.

Related: Read a FREE issue of All About History magazine

Early years

Born Margaret Roberts on Oct. 13, 1925, Thatcher had a humble but comfortable upbringing, living with her family in an apartment above her parents' grocery store in Grantham, Lincolnshire. In addition to being a grocer, Thatcher's father, Alfred Roberts, was also a preacher and a local politician, having held a seat on the local town council for several years and serving as Mayor of Grantham from 1945 - 1946. Her father's religious devotion and interest in politics, no doubt, influenced Thatcher's views and career path as an adult.

She was a determined student, and after attending grammar school on a scholarship, was granted admission to Oxford in 1943 — an ambition still firmly out of reach of most women in the years after World War II. She graduated Oxford in 1947 with a chemistry degree, having specialized in X-ray crystallography while under the supervision of Dorothy Hodgkin, a Nobel Prize-winning chemist.

Related: Gallery: A treasure trove of Britain's old newspapers

After graduating, Thatcher worked as a chemist for BX Plastics in Colchester, Essex. In 1948 she applied for a job at Imperial Chemical Industries, but was denied because she was "headstrong, obstinate and dangerously self-opinionated," according to a BBC article. Unperturbed, she continued her career as a chemist while satisfying her appetite for politics by joining the local Conservative Association. Then, in the 1950 and 1951 general elections, she was the Conservative candidate for a Labour seat in Parliament. She lost both times but stood out among her competition as the youngest and only woman candidate, according to John Blundell's biography "Margaret Thatcher: A Portrait of the Iron Lady" (Algora, 2008).

In 1949, soon after being selected as a Member of Parliament (MP) candidate, Thatcher (still Roberts at that time) met Denis Thatcher, a World War II veteran and successful businessman, who had just recently divorced. Margaret thought Denis was "nice," but wasn't swept off her feet by any means, according to a report by The Telegraph. Nonetheless, the two stayed in touch and married on Dec. 13, 1951.

Her rise in politics

After failing to be selected as the Conservative candidate for the 1955 by-election to replace Sir Waldron Smithers, a Conservative MP who had died, Thatcher took a step back from politics to focus on raising her two-year-old twin children, according to John Campbell's book "Margaret Thatcher Volume One: The Grocer's Daughter" (Johnathan Cape, 2000).

Finally, in 1959, after a challenging campaign, Thatcher was elected as the Conservative MP for the county of Finchley. For the next decade, she served in a variety of political posts, consistently attracting attention for being a young woman in politics and for her sometimes controversial views, such as her support for capital punishment.

Her first role as a top government official came in 1970, when Prime Minister Edward Heath appointed Thatcher to his Cabinet as Secretary of State for Education and Science. During her time in office she oversaw the expansion of comprehensive schools, which are secondary schools that welcome all students rather than selecting students based on academics or wealth, as grammar schools do. There were supporters and detractors of comprehensive schools, but at the heart of the criticism was the belief that it underpinned class-based society and stifled aspiration, especially in the poorer disadvantaged areas.

Thatcher's popularity in her Cabinet role continued to decline when she abolished free milk for school children over seven years old as part of the government's broader effort to cut spending. Many people began to see her as an enemy of the health and wellbeing of the nation's future, and the phrase "Mrs. Thatcher, milk snatcher" was born. However, government papers revealed later that Thatcher opposed the decision to stop the program, but was forced to go through with it by the Treasury, according to The Independent. She was so upset by the negative response that she almost left politics.

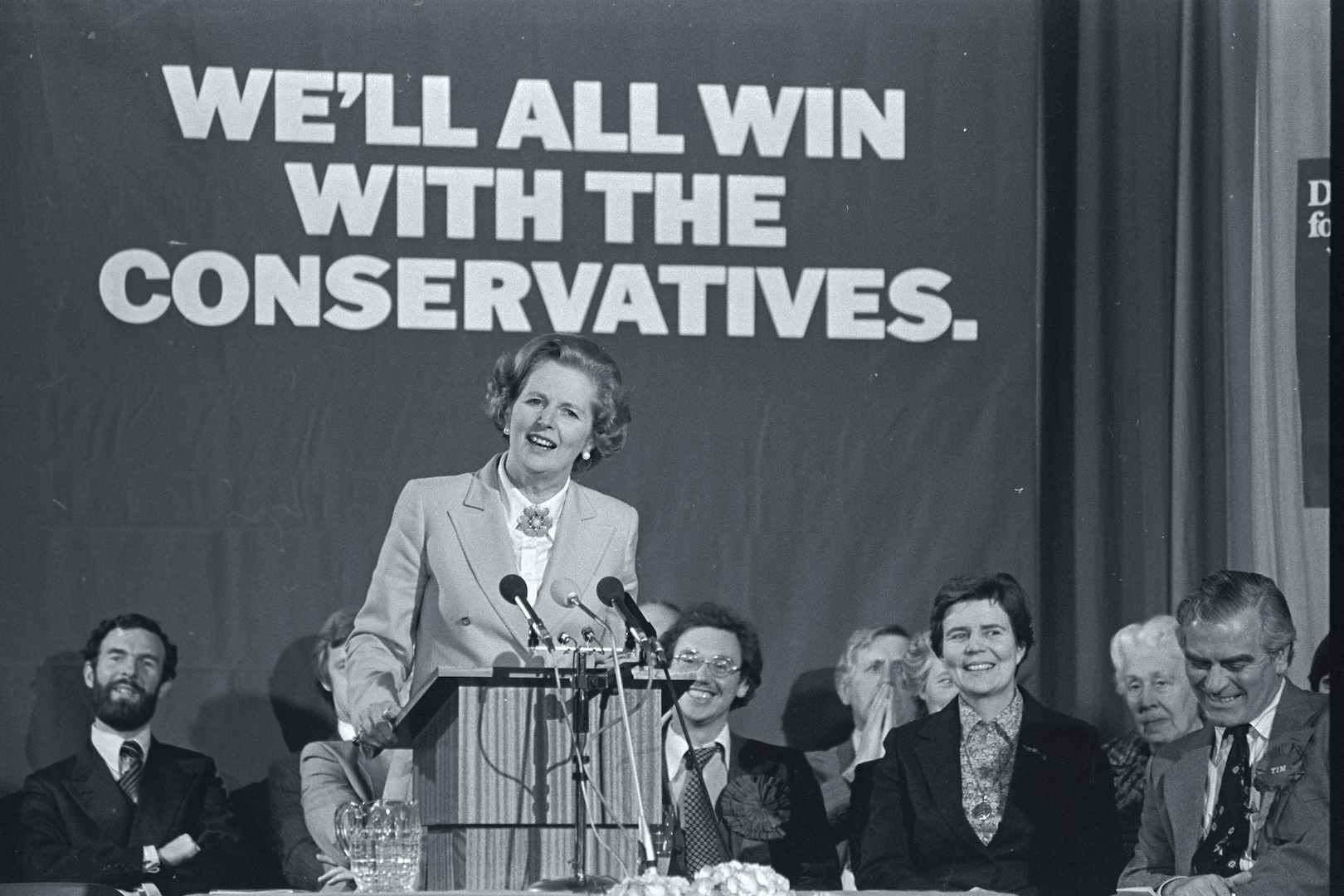

But she persisted, and as Heath's government struggled through the 1970s, Thatcher began to emerge as a political leader. In 1975, she was elected as the Conservative Party leader and Leader of the Opposition, making her the first woman to lead a major political party in Britain, according to the Margaret Thatcher Foundation.

In January 1976, Thatcher delivered a speech at Kensington Town Hall in London, and spoke about the Iron Curtain — the political boundary that separated Europe during World War II. A Soviet newspaper story about the speech referred to Thatcher as the "Iron Lady," according to the Margaret Thatcher Foundation. The nickname followed her throughout the rest of her career and long after.

Prime Minister Thatcher

In 1979, Thatcher became not only Britain's first woman prime minister, but the first woman to govern a western democracy.

Advocating for people to be less dependent on the state and more able to make their own choices, her policies were bold and controversial in equal measure; increasing indirect taxes and reducing contributions from government. Having inherited a poor, failing economy, her solutions were harsh and difficult to bear for the poor and disadvantaged in society. However, her grit and determination prevailed and her famous "the lady's not for turning" speech at the Conservative Party Conference in 1980 left her critics in no doubt as to her vision and strength of her will.

Not everyone suffered under Thatcher's government. Her focus was to inject momentum and strength into the economy with initiatives such as the ability of tenants to buy their council house (Britain's version of communal public housing), and for anyone to be allowed to purchase shares in the main utility companies as part of a massive privatization program; all pursued with a firm belief in giving all men and women greater choices in where to put their money and a pride in their future.

Related: Who inherits the British throne?

National pride was at the center of a pivotal moment in Thatcher's leadership. Following the invasion of the Falkland Islands by Argentina in 1982, and with diplomatic channels exhausted, the prime minister took the momentous decision to create and deploy a task force of thousands to sail down to the South Atlantic to retake the British Overseas Territory. It was a move that galvanised a nation, united in a patriotic fervor and single belief that Britain was still a major player to be reckoned with on the world stage. With the Argentinian army forced to surrender, a hero's welcome awaited the returning task force and Thatcher referred to the "Falklands spirit" for many years afterwards, The Guardian reported. But it came at a price: over 250 British dead that were mourned by a nation. There was criticism from some quarters, but the majority voice was one of support, and for a while she was able to ride the crest of the wave.

As a player on the international stage she became a force to be reckoned with. Her role in aiding the peace process of Northern Ireland by signing the Anglo-Irish Agreement is in direct contrast to her personal attacks on the Republican hunger strikers. Her relations with U.S. President Ronald Reagan gave her the platform from which she could project the image of Britain as a global influence to be taken seriously and listened to, even if this meant a lack of popularity at home. The American cruise missiles based at Greenham Common, the use of British Royal Air Force bases for U.S. aircraft to bomb Libya; all this played into the hands of those accusing Thatcher of being a puppet of the United States.

But Thatcher did not view herself so blinkered in this way, and as part of her global char, strategy, was even willing to engage with those at the complete opposite end of the political spectrum; she was the first British Prime Minister to visit the People's Republic of China, and she formed closer ties with the reformist policies of Mikhail Gorbachev as he guided the Soviet Union out of the Cold War.

But the glittering glamour of foreign policy was to be overshadowed by a grim harsh reality for many living under Thatcher's domestic agenda. The introduction of the Community Charge, or "Poll Tax" as it became known, became synonymous with Thatcherism at its most brutal, with taxation of property moving to taxation of individuals thereby dividing the nation along lines of the have and have-nots, which for many was the same as class. Protests were country-wide and many of the bigger cities saw violence and riots, The Independent reported.

Related: Margaret Thatcher: Why powerful women face more stress

Having seen a previous traditional, conservative government brought to its knees by union strike action, Thatcher was determined to prevent it from happening again. But when she clashed with the unions in 1984 over the closure of unprofitable coal pits, it was a confrontation of epic proportions, and one she intended to win.

Arthur Scargill, President of the National Union of Mineworkers refused to hold a strike vote, which meant the strike was deemed unlawful. Whole communities suffered as the industrial action dragged on, according to Martin Adeney and John Loyd's book "The Miners' Strike, 1984-1985" (Taylor and Francis, 1988). Images of violent clashes between strikers and police were beamed around the world. Thatcher stood firm, and was living up to her "Iron Lady" reputation, but many saw her as cold and heartless, uncaring for the damage she was causing to honest hardworking families. After a year, the unions were forced to back down, opening up a new era in industrial relations and leaving the unions a shadow of their former selves.

Thatcher's legacy

The era of Thatcher was an era of change. In response to political and social turmoil of the 1970s the world of the 1980s and beyond became a very different place, but at what cost? For her it was no pain, no gain. For others, it was a brutal dissection of society. She enabled huge numbers of people to own their own homes and to benefit from shared ownership, but she stripped entire communities of their livelihood and left many feeling targeted and victimised by unfair taxation.

Related: 'Iron Lady' Margaret Thatcher dies at 87

It cannot be denied that she broke the mould when she came to power, only to be criticised by some for not governing more like a woman and by others for not being more like a man. Her resolve, focus and self belief cannot be questioned nor her ability to ignite passions on all sides. As a world figure she became a colossus, but by her third term in office the cracks were beginning to show and former loyalties turning against her until, eventually, she perhaps stayed just a little too long and went out on a whimper rather than a bang. While her advocacy of laissez-faire economics and individual self-determination lives on as the right-wing philosophy we call Thatcherism, her real legacy is in how she transformed Britain — even if we're still debating if it was for better or worse.

Additional resources:

- Find archived transcripts of Thatcher's speeches and more information about the prime minister, from the Margaret Thatcher Foundation.

- Read more about Thatcher's time in office, according to the British government

- Here's another biography of Thatcher, published by Churchill College.

This article was adapted from a previous version published in All About History magazine, a Future Ltd. publication. To learn more about some of history's most incredible stories, subscribe to All About History magazine.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.