Antarctica's 'Doomsday Glacier' could meet its doom within 3 years

Thwaites Glacier is roughly the size of Florida, and holds enough ice to raise sea levels over two feet.

Time is melting away for one of Antarctica's biggest glaciers, and its rapid deterioration could end with the ice shelf's complete collapse in just a few years, researchers warned at a virtual press briefing on Monday (Dec. 13) at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU).

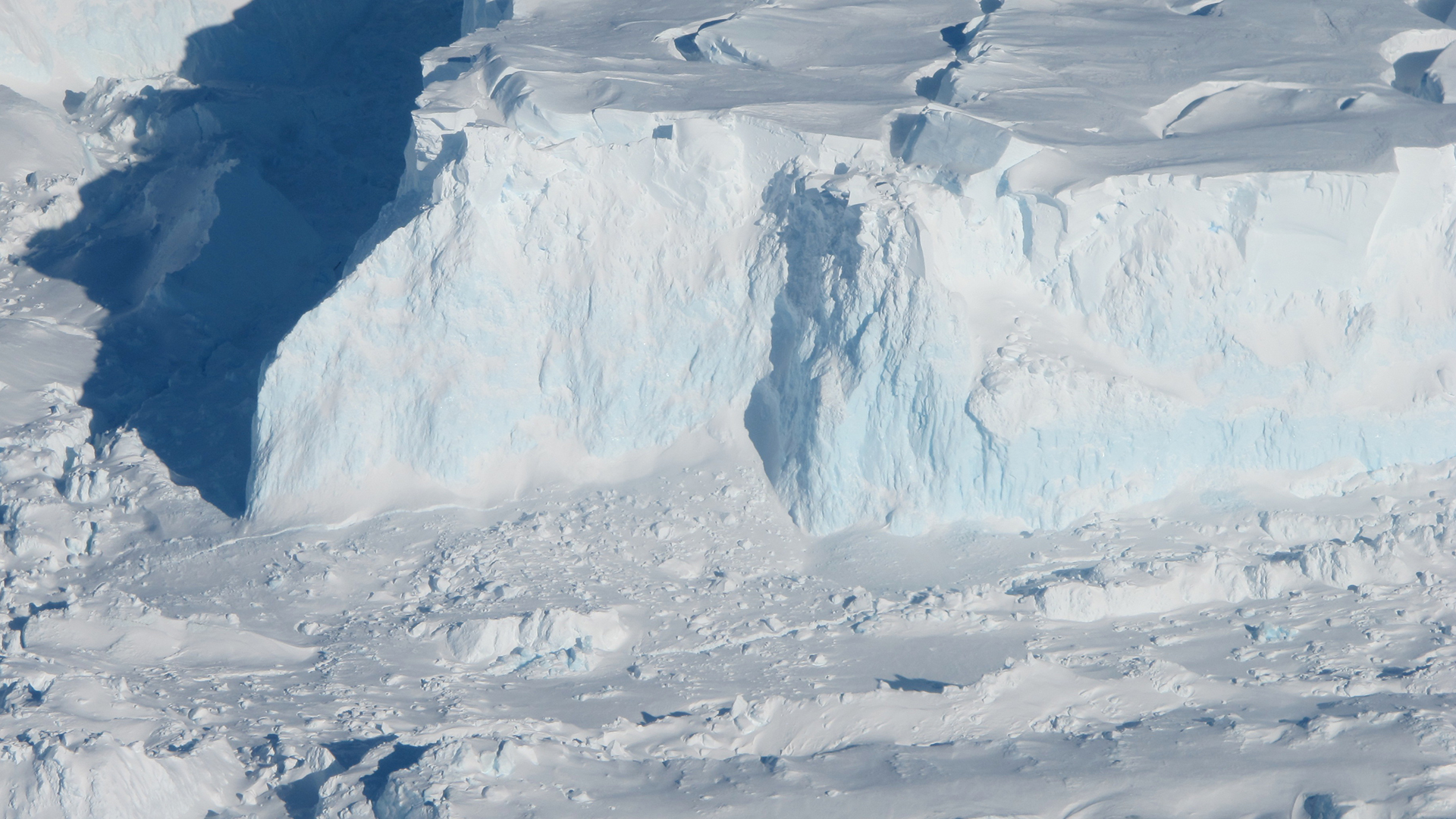

Thwaites glacier in western Antarctica is the widest glacier on Earth, spanning about 80 miles (120 kilometers) and extending to a depth of about 2,600 to 3,900 feet (800 to 1,200 meters) at its grounding line — where the glacier transitions from a land-attached ice mass to a floating ice shelf in the Amundsen Sea. Thwaites is sometimes referred to as the "Doomsday Glacier," as its collapse could trigger a cascade of glacial collapse in Antarctica, and the latest research from the frozen continent suggests that doomsday may be coming for the dwindling glacier even sooner than expected.

Warming ocean water is not just melting Thwaites from below; it's also loosening the glacier's grip on the submerged seamount below, making it even more unstable. As the glacier weakens, it then becomes more prone to surface fractures that could spread until the entire ice shelf shatters "like a car window" — and that could happen as soon as three years from now, researchers said at AGU, held in New Orleans and online.

Related: Time-lapse images of retreating glaciers

Over the last decade, observations of Thwaites showed that the glacier is changing more dramatically than any other ice and ocean system in Antarctica, thanks to human-induced climate change and increased warming in Earth's atmosphere and oceans. Thwaites has already lost an estimated 1,000 billion tons (900 billion metric tons) of ice since 2000; its annual ice loss has doubled in the past 30 years, and it now loses approximately 50 billion tons (45 billion metric tons) more ice than it receives in snowfall per year, according to The International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration (ITGC).

If Thwaites were to break up entirely and release all its water into the ocean, sea levels worldwide would rise by more than 2 feet (65 centimeters), said ITGC lead coordinator Ted Scambos, one of the presenters at AGU and a senior research scientist at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES).

"And it could lead to even more sea-level rise, up to 10 feet [3 m], if it draws the surrounding glaciers with it," Scambos said in a statement, referring to the weakening effect one ice shelf collapse can have on other nearby glaciers.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Because Thwaites is changing so quickly and could significantly affect global sea-level rise, more than 100 scientists in the United States and the United Kingdom are collaborating on eight research projects to observe the glacier from top to bottom; results from several of those teams were presented at AGU.

"We're about at the midpoint of The International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration," Scambos said at the briefing. "We've got a few more years to go to assemble further results and integrate them, so we have a better understanding of this glacier moving forward."

These findings, as well as the ongoing work by ITGC and other scientists in Antarctica, will inform policymakers' strategies for tracking the impacts of glacial melt on sea-level rise over the coming decades, and how that in turn will affect coastal communities around the world, according to the presenters.

Melt from below

At Thwaites, scientists bored holes through the ice to peer at the ocean hundreds of meters underneath, and other researchers deployed remote-controlled diving robots to study the glacier's grounding zone. They took temperature readings and measured salinity in the ocean, confirming that waters deep under the ice were warm enough to cause significant melt.

Another group of scientists found that tidal activity could interact with the ice overhead to actively pump warm water farther inland through channels that were already carved by melt, thereby accelerating Thwaites' deterioration, said presenter Lizzy Clyne, an adjunct professor at Lewis and Clark College in Portland, Oregon.

"When you have low tide, the floating ice shelf portion sinks down," Clyne said at AGU. "This acts kind of like a lever, and can actually pull up a section a little bit inland that can pull water in. And then the opposite happens when you have high tide and the water level rises — the floating section rises up." This up-and-down movement, known as tidal pumping, pulls water farther inland and weakens even more of the glacier, Clyne explained.

"Hundreds of icebergs"

Once-solid ice masses on Thwaites that formerly helped to hold the ice shelf together are also breaking down; the glacier's icy "tongue" — a part of the ice shelf that protrudes seaward — on the western side is now "just a loose cluster of icebergs and no longer influences this eastern, more stable section of the ice shelf," according to AGU presenter Erin Pettit, an associate professor of geophysics and glaciology at Oregon State University. When the tongue was more solid, it slowed the flow of the eastern ice shelf toward the ocean. But with the loss of that resistance, the flow of the eastern shelf has shifted over the past 10 years. Cracks are rapidly spreading through the ice, and that portion of the shelf will likely shatter "into hundreds of icebergs" within just a few years, Pettit said.

The effect would be somewhat like that of a car window "where you have a few cracks that are slowly propagating, and then suddenly you go over a bump in your car and the whole thing just starts to shatter in every direction," she said.

Some of the changes in Thwaites' ice are so swift and dramatic that scientists are watching them happen in real time, such as the appearance two years ago of a giant rift on the eastern ice shelf, Pettit said. A series of recent satellite images showed the lengthening crack heading right for the spot where the researchers had planned to set up their field site for the season. While the crack wasn't moving fast enough to threaten their field work that year, seeing its implacable advance was still a sobering moment; the researchers nicknamed the crack "the dagger," Pettit said at the briefing.

While the immediate prognosis is grim for Thwaites' ice shelf, the longterm forecast for the rest of the glacier is less certain. Should the shelf collapse, the glacier's flow will likely accelerate in its rush toward the ocean, with parts of it potentially tripling in speed; other chain reactions could also play a part in driving accelerated ice fracturing and melt, Scambos said at AGU. But the timeframe for those changes will be decades rather than a handful of years, according to the briefing.

Meanwhile the ITGC teams will continue to monitor and analyze changes in the ongoing interplay between glacier, ice shelf and ocean on Thwaites, to help world leaders and policy makers prepare for what comes next.

"That will help characterize what the next century is going to be like from this part of Antarctica," Scambos said. "We think it's going to be led by changes in Thwaites Glacier."

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.