Dramatic transformation of the Arctic landscape may be permanent

From vanishing sea ice to blistering air temperatures to zombie fires, climate change is reshaping the Arctic. And that transformation may be permanent, researchers said on Tuesday (Dec. 8) at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU).

The Arctic has warmed and melted at an alarmingly accelerating pace over the last 15 years, and the impacts are accumulating so rapidly that "there's no reason to think that in 30 years anything will be as it is today," Rick Thoman, an Alaska climate specialist with the International Arctic Research Center (IARC) at the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF), said at the conference, held virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic, on Tuesday.

For the last 15 years, the Arctic Program at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has released the Arctic Report Card (ARC), a yearly summary of the northern region's current environmental status. The ARC has documented shifts across this vulnerable region as Earth warms, and has outlined repercussions for ecological systems, weather patterns and human communities.

Related: 10 signs that Earth's climate is off the rails

This year's news was not good: June snow cover across the Eurasian Arctic was at its lowest in 54 years; coastal permafrost erosion is increasing; and glaciers and ice sheets in Greenland continued a trend "of significant ice loss," according to the report.

Arctic warming is happening twice as quickly as warming elsewhere on Earth, and this year brought air temperatures that were 3.4 degrees Fahrenheit (1.9 degrees Celsius) higher than average, making 2020 the Arctic's second-hottest year since at least 1900. Ocean temperatures in August were also hotter, as much as 5.4 F (3 C) warmer than average sea-surface temperatures in August from 1982 to 2010.

Warming seas, melting ice

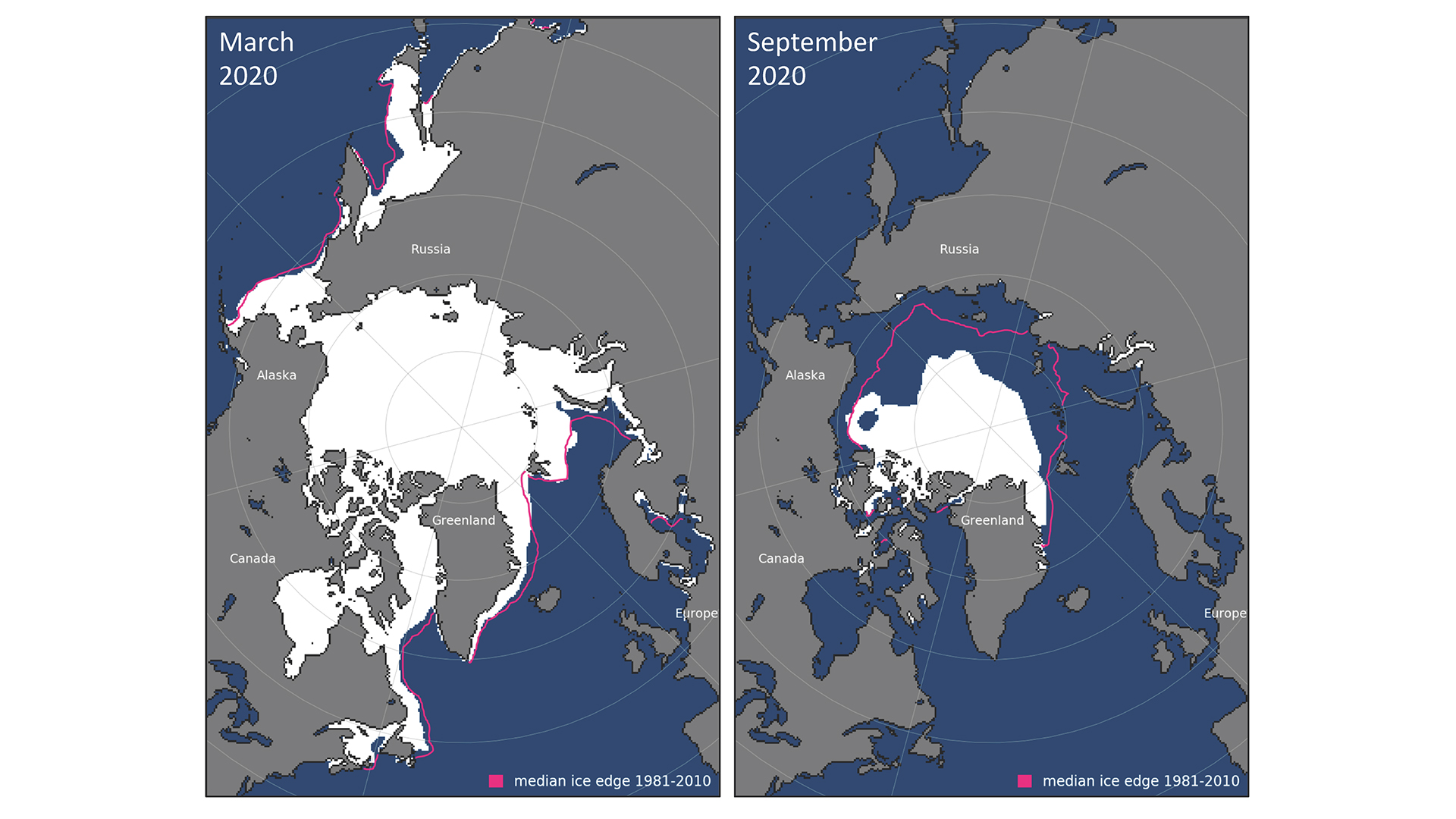

Sea-ice loss began earlier than usual in the spring, with end-of-summer ice coverage diminishing to the second-lowest in 42 years of record-keeping. And a landmark year-long research expedition — the Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate (MOSAiC) — revealed the extent of ice loss to an international team of researchers in real-time.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

MOSAiC scientists traveled to the Arctic on an icebreaker ship that embedded in an ice floe to drift in the Arctic Sea, enabling experts to set up monitoring stations on the ice, conduct surveys and collect data, said Matthew Shupe, a senior research scientist with the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) at the University of Colorado in Boulder, and a member of the MOSAiC expedition.

While much of the data is yet to be analyzed, the expedition found sea-ice cover to be "very thin," and it was challenging for them to find a suitable ice floe to follow, Shupe said at AGU. The sea ice where scientists had hoped to establish camps would often crack and shift. Strong ocean circulation patterns that prevailed across the Arctic in 2020, also propelled MOSAiC scientists across the Arctic faster than they had planned, with rapid drift pushing their observatory to the very edge of the ocean's ice cover, Shupe said.

Zombie fires

Persistent heat and dryness also sparked more than 700 wildfires that burned over 3,800 square miles (9,800 square kilometers) in the northern latitudes, according to the ARC. Fire seasons in the region are variable, but since the beginning of the 21st century, years with significant fire damage in the Arctic have become more common, said ARC co-author Alison York, an expert in Alaska fire ecology at the IARC and coordinator of the Alaska Fire Science Consortium.

Arctic fires are fueled not only by trees, but also by material known as duff — layers of dead plants and moss. Extreme cold in the Arctic slows decomposition, so dead plant material breaks down slowly and builds up in layers on the ground, York said at AGU. Duff stores about 30% to 40% of global soil carbon and insulates Arctic permafrost, but warm conditions can make duff highly flammable. When duff ignites, even if the flames die down the material can smolder all winter, flaring to life again in the summer. These so-called zombie fires play a key role in stoking destructive fire seasons in northern latitudes, and 2020 was "a record fire year" within the Arctic Circle, with many of these "undead" fires and millions of acres burned, York said.

Success for whales

Current warming trends in the Arctic are unlikely to slow without drastic efforts to dial back global climate change. In fact, models show that the more ice the Arctic loses, the faster it will warm, and warming in the north is likely to be baked in beyond the levels for the rest of the planet, said James Overland, a research oceanographer with NOAA's Pacific Marine Environment Laboratory.

"While we may be able to hold the globe down to a 2-degree [Celsius] increase, the Arctic will see more like 4 to 5 degrees of warming," Overland said at AGU. "What we do now will greatly impact what happens in the second half of the century," he added.

One bit of good news in the report involves the Arctic's bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus), the only baleen whale species that lives exclusively in the Arctic and doesn't travel to southern latitudes to birth its calves. These whales were once hunted nearly to extinction, but their populations have climbed over the past 30 years, in part due to the increase in nutritious zooplankton that ocean warming has brought to the Arctic, and the whales' health and numbers now stand as "a conservation success story," said ARC co-author Craig George, a biologist with the Department of Wildlife Management in Alaska's Northern Slope Borough.

But it remains to be seen if the Arctic's bowheads will continue to thrive. Thinning sea ice further increases the whales' vulnerability to orca attacks, and as oceans warm and other baleen whale species such as humpbacks and fin whales become more frequent visitors in Arctic waters, bowheads face increased competition, challenging their recovery and making the future of this long-lived species less certain, George said at AGU.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.