Baby dinosaurs hatched in the Arctic 70 million years ago

It's likely these tiny dinos lived in chilly Alaska year round.

Baby dinosaurs toddled around the chilly region that is now the Alaskan Arctic about 70 million years ago, according to the "unexpected" discovery of more than 100 baby dinosaur bones and teeth there, a new study reports.

It was surprising to find evidence of a prehistoric nursery in such a cold place, the researchers said. Even during the warm Cretaceous period (145 million to 66 million years ago), Alaska had an average monthly temperature of about 43 degrees Fahrenheit (6 degrees Celsius), and for about four months of the year, the dinosaurs would have lived in permanent darkness and dealt with snowy weather, they said.

The Prince Creek Formation of northern Alaska, where the fossils were found, is "the farthest north that dinosaurs ever lived," study co-lead researcher Gregory Erickson, a paleobiologist at Florida State University, told Live Science. "I don't think it was possible for them to live any farther north," as what is now Alaska was shifted closer to the North Pole than it is today. "It's right up there with Santa Claus," he said.

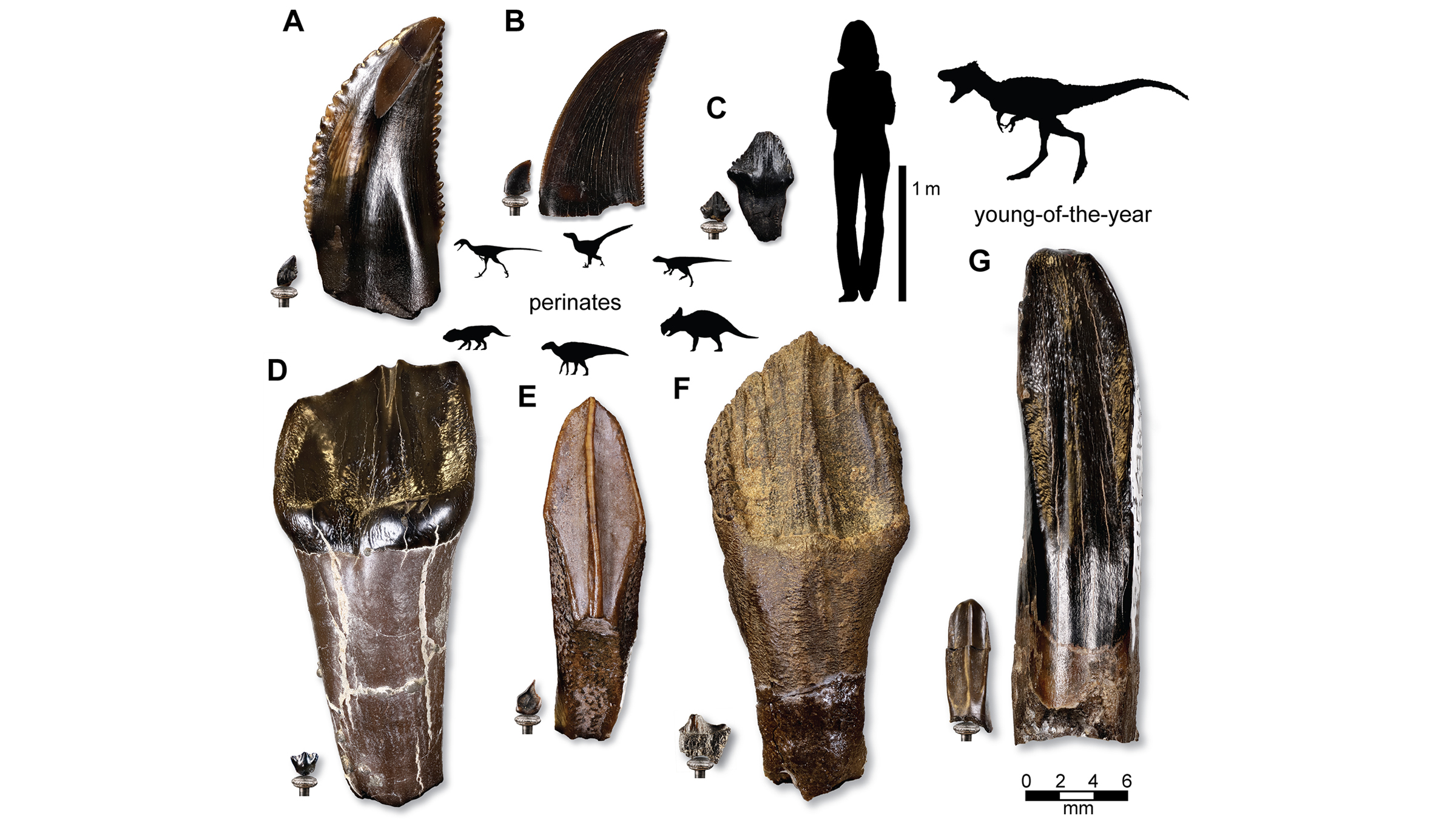

After analyzing the babies' teeth and bones, the research team determined that the remains belonged to seven different dinosaur species. The discovery indicates that dinosaurs likely lived in this frigid region all year, as the babies would have been too small for annual migrations shortly after hatching, Erickson said. If these wee dinosaurs and their parents stayed in Alaska year-round, they were likely warm-blooded, or endothermic — a feature that would have allowed them to stay active even when temperatures dropped, he added.

Related: Album: Discovering a duck-billed dino baby

Researchers have known that dinosaurs lived in polar regions since oil workers found dinosaur bones there in the 1950s, Erickson said. In the following decades, scientists with the University of Alaska Museum of the North discovered the remains of teensy baby dinosaurs in the state.

"Our work is like panning for gold, finding little bones in a sea of sediment," said study co-lead researcher Patrick Druckenmiller, a professor of geosciences and the director of the University of Alaska Museum of the North. Undergraduate and graduate students have contributed thousands of hours of work to the project, which uncovered baby dinosaurs belonging to several herbivorous species of duck-billed dinosaurs, ceratopsians (horned dinosaurs), thescelosaurids (small, bipedal ornithopods) and pachycephalosaurids (dome-headed dinosaurs). They also found baby remains from carnivores, including tyrannosaurids, deinonychosaurs (maniraptoran dinosaurs) and ornithomimosaurians (ostrich-like dinosaurs).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The most recent surprise was the smallest ceratopsid tooth of which I am aware in North America, or anywhere really," Druckenmiller told Live Science in an email.

The winter months in the Alaskan Arctic at the time were probably the toughest, especially for the herbivores, whose food would have been either covered in snow or dead, Erickson said.

"How they pulled it off, we don't know," Erickson said. Some small dinosaurs might have burrowed and hibernated, but larger dinosaurs — such as duck-billed dinosaurs and tyrannosaurs — weren't able to burrow. "Maybe they just had to stick it out like a moose or musk oxen. Somehow, they got through," Erickson said.

Staying put and staying warm

Based on knowledge of dinosaur life cycles, the researchers concluded that these baby dinosaurs stayed put after hatching, as they wouldn't have had time to mature before winter set in. That's partly because dinosaur eggs took a long time to incubate — anywhere from three to six months, Erickson and colleagues determined in a 2017 study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

These long egg-hatching times, "combined with the fact that you had a very short growing season up there to flourish before the winter set in, [baby dinosaurs] just did not have time" to grow big enough before migrating southward, Erickson said. "There's no way that these tiny dinosaurs made the march down to Alberta to escape the winter."

There is evidence that some long-necked sauropod dinosaurs and duck-billed dinosaurs at lower latitudes of western North America migrated, but it's likely that the Alaskan dinosaurs, especially the smaller individuals, stayed put, the researchers said. Spending the winter in polar conditions would be challenging for cold-blooded, or ectothermic, creatures. In fact, paleontologists haven't found ectothermic animal fossils — such as those from crocodilians, lizards or snakes — at Prince Creek Formation, Druckenmiller said. Moreover, there's only one ectotherm known from the Alaskan Arctic today: the wood frog, which essentially turns into an ice pop in the winter.

Based on this, as well as endothermy results from other studies analyzing dinosaurs' rapid growth rates, it's "likely dinosaurs had some degree of endothermy to cope with winter conditions, particularly the low/no light and cold temperatures," Druckenmiller wrote in the email.

The study was published online Thursday (June 24) in the journal Current Biology.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.