Albert Einstein's lost letter to British engineer suggests 'unknown physics' in animal behavior

In a newly discovered letter written by Albert Einstein, the renowned physicist suggested there could be a link between the migrations of birds and "unknown" physical processes — many decades before researchers realized that birds might use quantum physics to navigate over long distances.

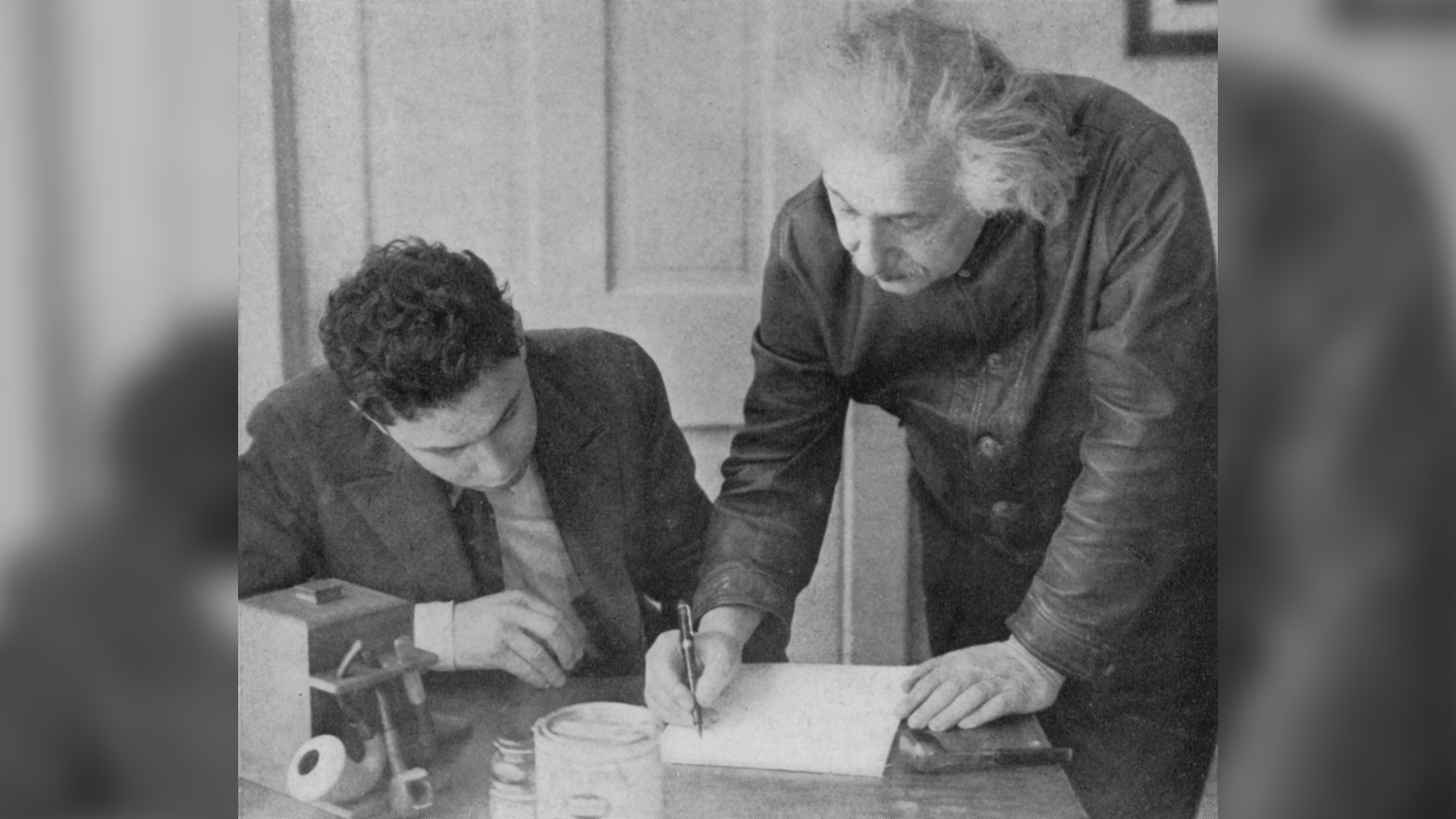

The typewritten letter by Einstein, then at the Institute for Advanced Studies at Princeton in New Jersey, was addressed to a former radar engineer in the British Royal Navy who lived in Bournemouth, England; its contents show both Einstein's extraordinary perception and his willingness to engage with the public about his work, said Adrian Dyer, a vision scientist at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in Australia.

"It was clear that Einstein received a good number of letters from the general public, and that he very frequently took the time to write back," Dyer told Live Science. "This is one of the elite researchers of the 20th century, but he was very much into open research — that you have to share your knowledge and talk to people."

Related: The 18 biggest unsolved mysteries in physics

Dyer and his colleagues detailed their research on the previously unknown letter in an open access study published May 10 in the Journal of Comparative Physiology A.

The researchers first became aware of the existence of the letter after publishing research in 2019 in the journal Science Advances that suggests bees are capable of elementary mathematics, including addition and subtraction.

A member of the public in the United Kingdom, retiree Judith Davys, heard a story about their research on the radio and found an article about it online. She then contacted the researchers to explain that Einstein had written to her husband in 1949 expressing similar ideas, Dyer said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Einstein letter

Dyer and his colleagues were astonished to learn about the 72-year-old Einstein letter and asked to see it. Researchers at the Albert Einstein Archives at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, where Einstein bequeathed his notes, letters and records after his death, then authenticated the letter.

The typewritten letter from Einstein to Judith Davys' now-deceased husband Glyn Davys is relatively short — only a few sentences — but it shows Einstein's thinking about how some types of animal behavior could be caused by unknown physical processes.

![Letter dated 18th October 1949 by Professor Albert Einstein at Princeton University (U.S.A.) to Mr Glyn (written Mr Ghyn [sic]) Davys in England with reference to the work of von Frisch and sensory perception of animals.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/eoFJXjukCEszYDeGs6tRaS.jpg)

Dyer said the original letter from Davys to Einstein — which appears to be lost — seems to have raised the issues of echolocation by bats and the perception of polarized light by bees. Glyn Davys' ideas may have been inspired by scientific articles at that time on research into the perception of bees by scientist Karl von Fritsch, who was personally known to Einstein, Dyer said.

Davys had worked on early radar systems in the Royal Navy during World War II, and seems to have expressed the idea that some animals could use similar methods to navigate.

"We presume Glyn Davys was a pretty smart engineer, and that he wrote to Einstein in that context, asking about animal senses and navigation," Dyer said. "That letter is lost, so we had to reverse engineer from the evidence what was plausible."

Famed scientist

Much of Einstein's work underpins the fundamental technologies of the 21st century, including his theory of general relativity that enables corrections for the GPS system used on smartphones and also governs the large-scale structure of the universe.

Related: 8 ways you can see Einstein's theory of relativity in real life

He was also an early proponent of the concepts of quantum physics, but he was uncomfortable with its implications. "God does not throw dice," he once famously wrote in 1926 to express his dissatisfaction with ideas of quantum mechanical randomness.

Einstein, who was Jewish, left Germany in 1933 after the rise of the Nazi party there; he worked for a time in an office in the mathematics department of Princeton University and in 1939 moved to the Insitute of Advanced Studies.

His letter to Davys suggests the possibility that studies of the navigational abilities of some birds during long-distance migrations could "one day lead to the understanding of some physical process which is not known."

Dyer notes that scientists have only recently suggested — for instance in 2005 in the journal Genome Biology — that a magnetic sense in birds that seems to enable them to navigate during migrations might be based on quantum physical processes in proteins called cryptochromes — many decades after Einstein's letter to Davys.

Although Einstein couldn't have known then that bird migrations might exploit quantum physical processes, his letter to Davys shows traces of the exceptional perception of ideas that he was famous for, Dyer said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.