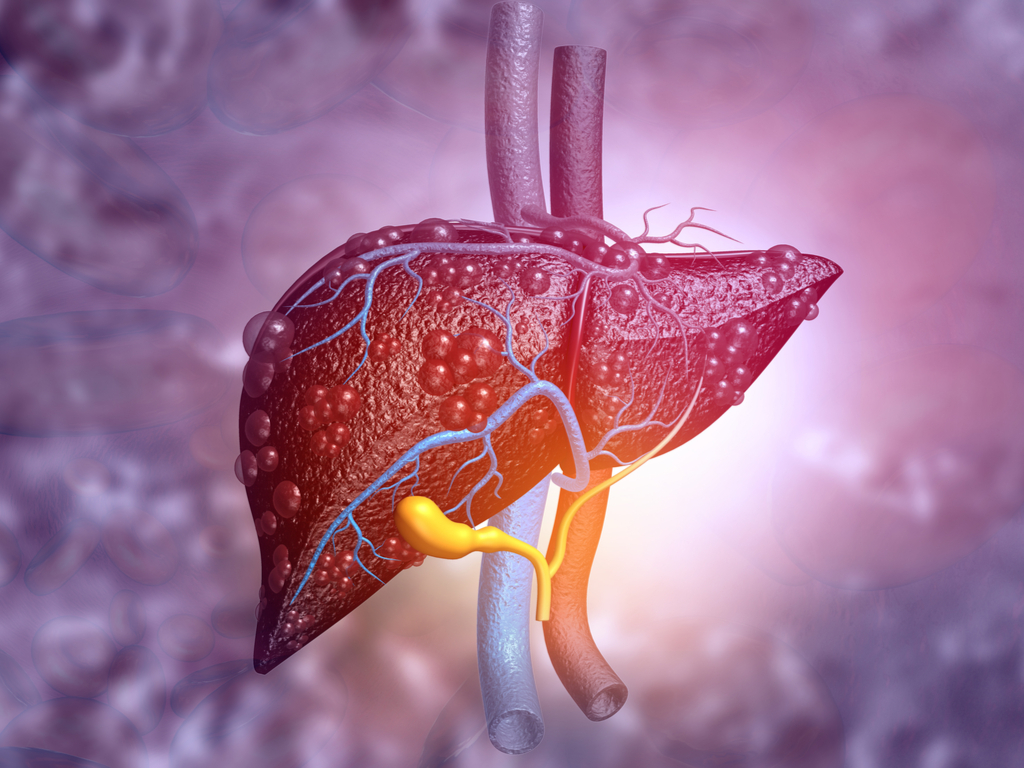

These Gut Bacteria Brew Their Own Booze, and May Harm Livers in People Who Don't Drink

Super-strains of gut bacteria produce harmful amounts of alcohol, which may to contribute to fatty liver disease.

It's common knowledge that drinking too much alcohol can lay waste to your liver. But now, researchers have spotted a strain of gut bacteria that produces its own booze in copious amounts — high enough to potentially pose a risk of liver problems in people who don't drink at all.

Although much more research is needed to confirm the results, they suggest that these boozy bacteria may contribute to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a condition in which fat builds up in the liver for reasons unrelated to alcohol consumption.

The researchers first stumbled upon this unusual microbe while they were studying a patient with a curious condition: The patient had so-called auto-brewery syndrome (ABS), an extremely rare condition that leaves people drunk after eating sugary food. In the week before he sought medical care, the unfortunate patient became inebriated each time he consumed a carbohydrate-rich meal and his blood-alcohol concentration had occasionally spiked to potentially lethal levels, around 0.4%. He was even suspected to be a "closet drinker" by his friends, according to the new study, published today (Sept. 19) in the journal Cell Metabolism.

ABS has been linked to yeast infections, wherein the fungus ferments alcohol in the intestines just as it brews beer in barrels; but in this case, yeast wasn't the culprit.

The researchers looked to their patient's poop for answers. They found, not yeast, but strains of alcohol-producing bacteria called Klebsiella pneumonia. This is the first time that a bacterium has been linked to ABS, study co-author Jing Yuan, a professor and director of the bacteriology laboratory at the Capital Institute of Pediatrics in Beijing, told Live Science in an email. Though the common gut bacteria poses no problem in healthy people, the microbe appeared to be producing four to six times the normal level of alcohol in the patient.

Besides becoming intoxicated, the patient also suffered from severe liver inflammation and scarring due to a buildup of fat in the organ, his doctors noted. The condition, called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, is a progressive form of NAFLD, and the researchers wondered if others with the disorder might carry the same "super-strain" of boozy bacteria.

Related Liver: Function, Failure & Disease

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team sampled the gut bacteria found in more than 40 people with NAFLD. Compared with about 50 healthy controls, the NAFLD patients hosted slightly more K. pneumonia in their guts than average. However, the alcohol-producing ability of those bacteria appeared unusually strong. About 60% of sampled NAFLD patients had high- and medium-alcohol-producing bacteria in their gut, while only 6% of the controls carried these strains.

To test if the boozy bacteria could cause fatty liver disease, the researchers isolated high-alcohol producing strains and fed them to "germ-free" lab mice, which don't have their own gut bacteria. Another group of mice received ethanol, while a control group ate only normal food for three months. Mice that ate the boozy bacteria began accumulating fat in their livers after one month and developed scarring after two months, similar to the mice fed ethanol. The extent of the liver damage correlated with the amount of alcohol produced — the more alcohol, the more damage. But the condition could be reversed with the administration of antibiotics.

The results suggest that K. pneumonia can indeed drive the progression of fatty liver disease, at least in mice.

"That's something unique — that just changing one bacteria does it," said Rohit Loomba, director of the NAFLD Research Center at the University of California, San Diego. Loomba noted that K. pneumonia may be one of several bacteria that could inflict liver damage in animal models. Studies to confirm the findings in humans will be key to learning how and whether K. pneumonia mingles with other gut microbes to drive liver disease progression, he said.

This isn't the first study to tie gut bacteria to liver disease. In a study published this year, Loomba and his colleagues found that people with NAFLD host distinct bacterial communities in their guts, depending on how far their disease has progressed. By analyzing these microbial signatures, the scientists were able to diagnose those with the most advanced stage of NAFLD, called cirrhosis, with 92% accuracy. In a similar 2017 study, the team learned they could predict the extent of scarring, or fibrosis, present in a patient's liver based on the composition of their gut microbiome.

If microbes like K. pneumonia do indeed play a role in NAFLD in people, they might someday serve as targets for the treatment of the disease, Loomba added.

In follow-ups with their human participants, the study authors found that levels of the high-alcohol producing strains dipped or disappeared in many of those who had undergone standard treatment for the disease and lost weight. The result suggests that there's a strong association between K. pneumonia and NAFLD progression, but whether the bacteria truly help cause the disease remains unclear.

Yuan and his colleagues are now recruiting study participants for a larger, long-term study in adults and another study in children to learn "why some people have high-alcohol producing strains of K. pneumonia in their gut while others don’t" and whether the bacteria actually contribute to disease.

- 7 Odd Things That Raise Your Risk of Cancer (and 1 That Doesn't)

- 10 Deadly Diseases That Hopped Across Species

- Microbiome: 5 Surprising Facts About the Microbes Within Us

Originally published on Live Science.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.