Has the tomb of Alexander the Great's mom been found? Experts are doubtful.

A researcher claims to have identified the long-lost tomb of Olympias, the mother of Alexander the Great. But other scholars are skeptical it's really her burial.

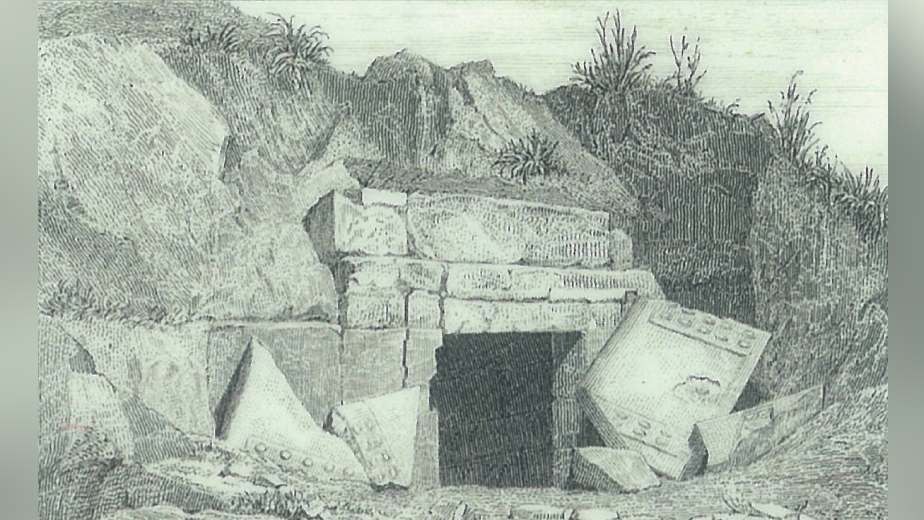

Archaeologists first discovered the tomb in 1850, not far from the Greek archaeological site of Pydna. The tomb has been studied at times by archaeologists since then. Recently, Athanasios Bintas, an emeritus professor of Greek studies at the University of Niš in Serbia, examined the tomb and now says it was used to bury Olympias. Made of stone, the tomb is 72 feet (22 meters) long and contains multiple chambers. The tomb's design has led archaeologists to date it to the late fourth to early third century B.C. As the tomb was robbed in ancient times, no bodies or grave goods have been found inside.

Alexander the Great conquered a vast empire that stretched from Macedonia to Afghanistan. After he died in 323 B.C., his empire fell apart, with his generals and officials fighting over who would control it. Amidst this chaos, Alexander's mother Olympias was in Macedonia trying to protect Alexander IV (the young son of Alexander the Great) and the boy's mother Roxane, one of Alexander's wives. An official named Cassander tried to gain power in Macedonia and sought to kill or kidnap Alexander's son and wife, according to ancient historical records.

Related: 10 reasons Alexander the Great was, well … great!

Forces loyal to Olympias tried to defeat Cassander, but they were forced to surrender after they ran out of food during a siege carried out at Pydna in 316 B.C. Shortly after that surrender, Cassander had Olympias killed. Then in 309 B.C., Cassander had Alexander IV and Roxane killed.

Though historical sources say that Cassander did not allow Olympias a proper burial, Bintas stands by his claim that her remains were interred in this elaborate stone tomb. "A dead queen was no longer dangerous for Cassander," Bintas told Live Science. The tomb was likely a more modest structure at the time of burial; but in 288 B.C. when Olympias' nephew Pyrrhus became king of Macedonia, he expanded her tomb.

The tomb's large size, its age and its proximity to Pydna (where Olympias was defeated) all support the claim that it was Olympias' tomb, Bintas said. Inscriptions found not far from the tomb contain lines that appear to mention Olympias' tomb, suggesting that it is likely nearby, he said. The inscriptions were described by the scholar Charles Edson in 1949 in the journal Hesperia and are now lost. Bintas has not yet published his arguments in an academic journal.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scholars react

Five scholars not affiliated with the research were either skeptical about the claim or wanted more information on Bintas' research before putting forward their opinion.

Related: Bones with names: Long-dead bodies archaeologists have identified

"It is far too soon to say [whether this is the tomb of Olympias], especially on the basis of so little specific evidence," said Elizabeth Carney, a professor of humanities at Clemson University, in South Carolina, who has conducted extensive research on Olympias.

Ian Worthington, a professor of ancient history at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia, expressed doubts that this is the tomb of Olympias. Ancient sources, Worthington noted, were clear that Cassander did not allow Olympias a proper burial; and since Cassander was afraid of rebellions, he would have barred such a tomb that could be used to rally Cassander's opponents. By the time Cassander died in 297 B.C., almost 20 years had passed since Olympias' death; Worthington said he doubts that someone would go to the trouble of building an elaborate tomb by that point.

Additionally, Worthington notes that just because the tomb is large does not mean that whoever was buried in it was noble. In fact, he said, a large tomb could be had by anyone with enough wealth to build it. "You could be wealthy but not necessarily noble," said Worthington. Another problem is that Olympias was originally from Epirus, in northwestern Greece. If someone wanted to give her a proper burial, Worthington thinks that it's more likely they would have brought her home to Epirus rather than bury her close to where she was killed.

Another scholar, Robin Lane Fox who is an emeritus fellow of classics at Oxford University, was even more doubtful. "There is no new evidence here," Fox said. "The tomb is well-known and was excavated in the 1850's [and] has been restudied since," with a recent "attempt to reconstruct it digitally," said Fox, also noting that Olympias might not have been given a proper burial in the first place.

"Nobody in the official Archaeological Ephorate [the government organization in charge of archaeology] is believing this allegation about Olympias," Fox said. "This conjecture of his [Bintas] is not at all persuasive."

One supporter of Bintas' claim, Liana Souvaltzi found a tomb in the 1990s in the Siwa Oasis in Egypt that she believes is that of Alexander the Great. Her claim garnered little support among scholars. In remarks published on the website Greek City Times, Souvaltzi commented on Bintas' claim, saying that "I was impressed by the size of this tomb, from which one understands that it must have belonged to a great person," adding that it "is a miniature" version of the tomb that Souvaltzi found in the oasis.

Originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.