Could E.T. Have Bugged a Space Rock to Listen In on Earthlings?

Aliens could have started watching us long ago.

Picture this: A hundred million years ago, an advanced civilization detects strange signatures of life on a blue-green planet not so far away from their home in the Milky Way. They try sending signals, but whatever's marching around on that unknown world isn't responding. So, the curious galactic explorers try something different. They send a robotic probe to a small, quiet space rock orbiting near the life-rich planet, just to keep an eye on things.

If a story like this played out at any moment in Earth's 4.5 billion-year history, it just might have left an archaeological record. At least, that's the hope behind a new proposal to check Earth's so-called co-orbitals for signs of advanced alien technology.

Co-orbitals are space objects that orbit the sun at about the same distance that Earth does. "They're basically going around the sun at the same rate the Earth is, and they're very nearby," said James Benford, a physicist and independent SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) researcher who dreamed up the idea that aliens might have bugged Earth via these co-orbitals while he was at a conference in Houston last year. If he's right, the co-orbitals could be a way to detect alien activity that occurred before humans even evolved, much less turned their attention toward the stars.

Related: 9 Strange, Scientific Excuses for Why Humans Haven't Found Aliens Yet

SETI gets ambitious

To be clear, even SETI researchers who like the idea of checking out Earth's co-orbitals acknowledge that it's a long shot.

"How likely is it that alien probe would be on one of these co-orbitals, obviously extremely unlikely," said Paul Davies, a physicist and astrobiologist at Arizona State University who was not involved in Benford's new paper on the idea, published Sept. 20 in The Astronomical Journal. "But if it costs very little to go take a look, why not? Even if we don't find E.T., we might find something of interest."

When humans began seriously contemplating how to find extraterrestrial intelligence in the 1950s, they began by simply listening, Davies said. Unfortunately, a half decade of scanning the heavens for radio or other transmissions from alien life has yielded only what Davies dubbed "the eerie silence" in his book of the same name (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010). So recently, Davies told Live Science, the SETI field has become interested in "technosignatures," or any sign of technology in the universe that wasn't created by humans.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

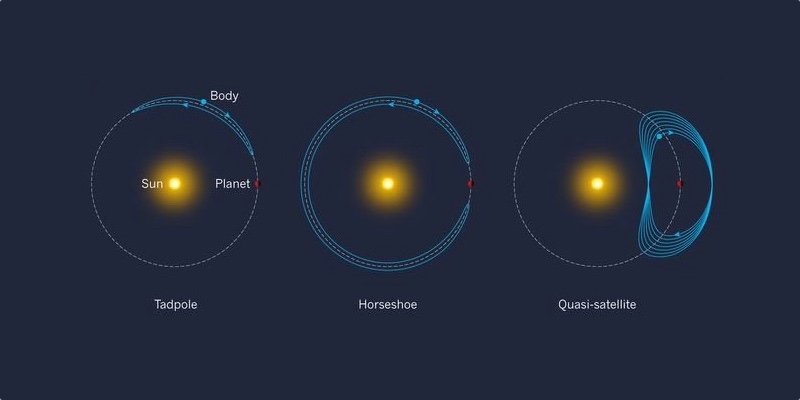

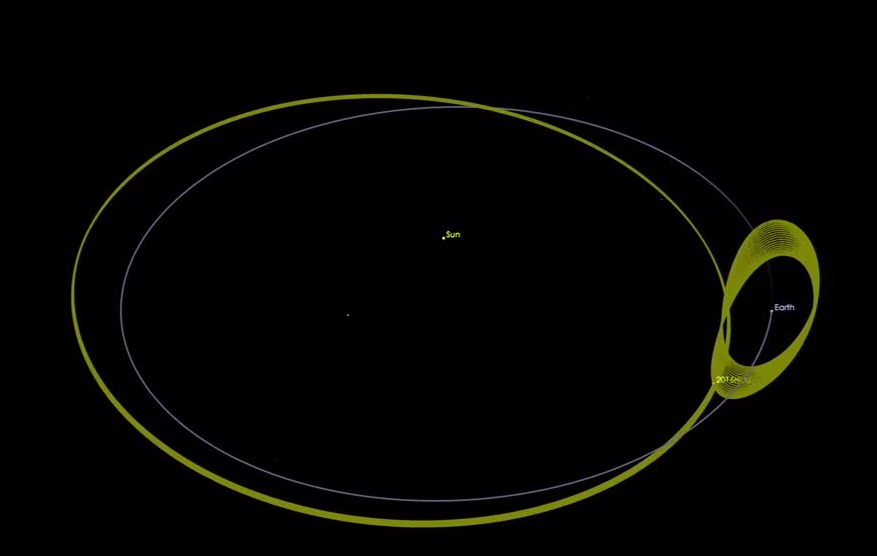

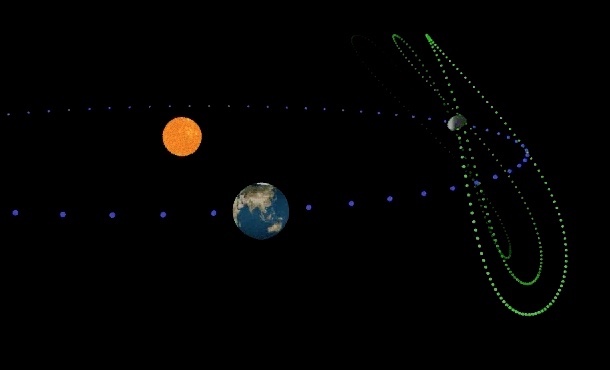

Probes on co-orbitals would be a prime example. Little is known about co-orbitals themselves, Benford said. The first was discovered in 1997, and most of the 15 or so other known co-orbitals near Earth were found after 2010. They hover around Earth in weird configurations, some of which look like horseshoes or tadpoles, as they make their journeys around the sun. The closest, known as "Earth's Closest Companion," is about 38 times as far away from Earth as the moon, and appears to be locked in a stable configuration with Earth that will last centuries, according to NASA. If co-orbitals stick by Earth for long periods, Benford said, they'd be a perfect spot for alien surveillance devices.

Finding the bugs

Earth's closest star other than the sun right now is Alpha Centauri, 4.37 light-years away. But every half million years or so, a star comes within about a light-year of Earth, Benford said, meaning that hundreds or thousands of stars (and their possible attendant planets) have been close enough to our planet during Earth's long history to make contact. Long-ago aliens may have observed nothing more exciting than photosynthesizing bacteria, or dinosaurs if they were lucky. But their probes could still be sitting on the co-orbital surface.

"This is essentially extraterrestrial archaeology I'm talking about," Benford said.

Related: Greetings, Earthlings! 8 Ways Aliens Could Contact Us

The moon might seem a better candidate for alien spyware than some teeny space rocks; but any given point on the moon is in darkness for two weeks at a time, Benford said. A probe would have to be able to store energy until it could charge in the sun again. Still, he and Davies have both argued for taking a close look at the high-resolution images of the moon sent back by NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, just in case something is there.

Benford suggests observing Earth's co-orbitals with optical and radio telescopes as well as pinging it with planetary radar — potentially sending a signal to any extraterrestrial civilizations that might, just maybe, still be listening. Sending small spacecraft to the co-orbitals would also be relatively cheap and easy, he said. In fact, China's space agency announced plans in April to send a probe to Earth's Closest Companion.

Seeking signs of intelligent extraterrestrials close to Earth is informative even if the search comes up empty, Benford said. That no one's heard or seen any extraterrestrial signals in 50 years or so doesn't mean much, given the mind-boggling time span of Earth's history. A lack of evidence spanning hundreds, millions or even billions of years would be much more convincing.

"If we don't find anything, that means no one has come to look at the life of Earth for over billions of years," Benford said. "That is a big surprise, a stunning thing."

- 13 Ways to Hunt Intelligent Aliens

- The 12 Strangest Objects in the Universe

- UFO Watch: 8 Times the Government Looked for Flying Saucers

- Apollo 11 moon landing showed that aliens might be more than science fiction

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.