Aliens haven't contacted Earth because there's no sign of intelligence here, new answer to the Fermi paradox suggests

A new paper claims that intelligent aliens would only be interested in contacting the most technologically advanced planets, and Earth doesn't make the cut.

Why haven't aliens gotten in touch? Maybe they think Earth is boring.

A new preprint paper published to the arXiv database suggests that intelligent extraterrestrials might not find planets that host life particularly interesting. If life has evolved on many planets in the galaxy, then aliens are probably more interested in the ones where there are signs not just of biology but technology, study author Amri Wandel, an astrophysicist at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, wrote in the paper. The paper is yet to be peer-reviewed.

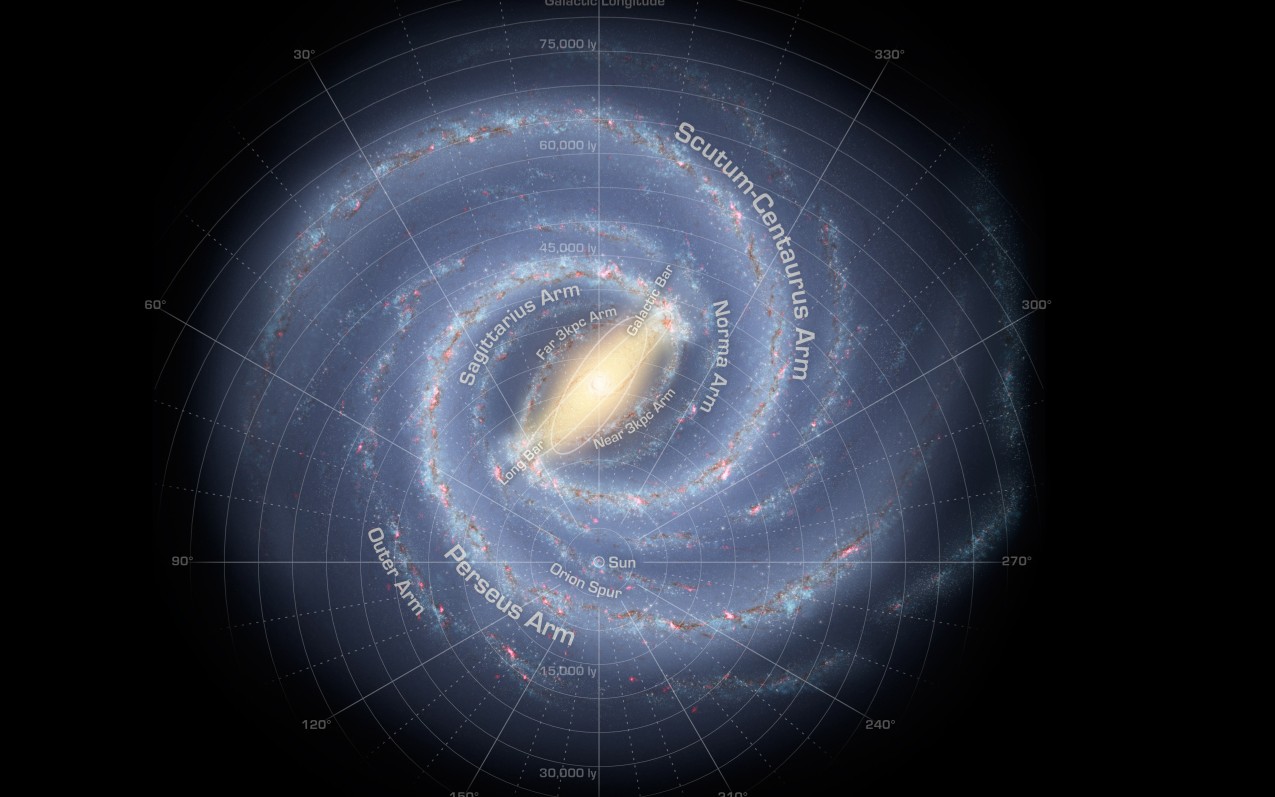

The study explores the Fermi paradox, which holds that given the age of the universe, it's likely that intelligent aliens would have developed long-distance space travel by now, and thus it’s likely that they would have visited Earth. The fact that they haven't (as far as we know) may be evidence that there is no other intelligent life in the Milky Way galaxy.

But experts have offered other explanations for the missing aliens: Perhaps they visited Earth in the past, before humans evolved or were capable of recording the visit. Or maybe long-distance space travel is more difficult than believed. Perhaps aliens evolved advanced civilization too recently to make it to Earth. Or they've deliberately decided not to explore the cosmos. It’s even possible that they’ve killed themselves off.

Related: Why have aliens never visited Earth? Scientists have a disturbing answer.

In the new paper, Wandel offers another possible explanation: that life is actually really common in the Milky Way. If many of the rocky planets orbiting in the habitable zone of stars host life, aliens probably aren't going to waste their resources sending signals to every one — they'd likely end up trying to communicate with alien algae or amoebas.

If life is common, intelligent aliens are likely much more interested in signs of technology. But tech signals may be tough to detect. Earth has only been beaming out signals detectable from space (in the form of radio waves) since the 1930s. In theory, these signals have now washed over about 15,000 stars and their orbiting planets, but that is a tiny fraction of the up to 400 billion stars in the Milky Way. Furthermore, Wandel wrote, it takes time for any return message from aliens to travel back, so only stars within 50 light-years have had time to respond since Earth started broadcasting off-planet.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Even worse, Earth's oldest radio signals weren't deliberately broadcast into space, so they're likely so garbled after about one light-year that aliens would be unable to distinguish them, according to Universe Today. (Earthlings sent out the first deliberate high-power broadcast to aliens with the Arecibo message in 1974, directed to the globular star cluster M13. Some scientists think it's time to send another.)

Wandel found that unless intelligent civilizations are very abundant, with more than 100 million technologically advanced planets in the Milky Way, it's likely that Earth's signals haven't reached another form of intelligent life. However, with time, and as our planet beams out more and more radio chatter, it becomes more likely that Earth's technological signals will find intelligent listeners, Wandel wrote.

The findings suggest that perhaps there are no intelligent civilizations within about 50 light-years of our planet, he wrote. But intelligent life could still be out there — they’re just waiting for our call.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.