Alzheimer's Directly Kills Brain Cells That Keep You Awake

Alzheimer's disease might be attacking the brain cells responsible for keeping people awake, resulting in daytime napping, according to a new study.

Excessive daytime napping might thus be considered an early symptom of Alzheimer's disease, according to a statement from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

Some previous studies suggested that such sleepiness in patients with Alzheimer's results directly from poor nighttime sleep due to the disease, while others have suggested that sleep problems might cause the disease to progress. The new study suggests a more direct biological pathway between Alzheimer's disease and daytime sleepiness.

Related: 6 Big Mysteries of Alzheimer's Disease

In the current study, researchers studied the brains of 13 people who'd had Alzheimer's and died, as well as the brains from seven people who had not had the disease. The researchers specifically examined three parts of the brain that are involved in keeping us awake: the locus coeruleus, the lateral hypothalamic area and the tuberomammillary nucleus. These three parts of the brain work together in a network to keep us awake during the day.

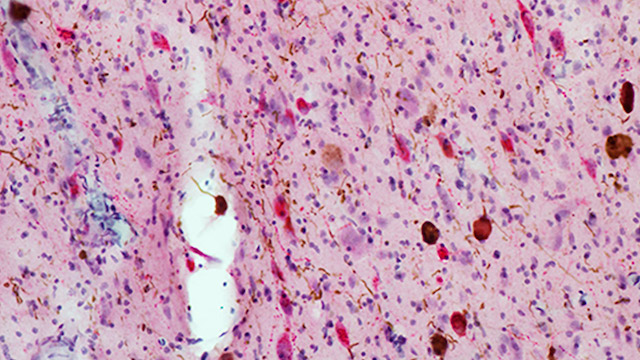

The researchers compared the number of neurons, or brain cells, in these regions in the healthy and diseased brains. They also measured the level of a telltale sign of Alzheimer's: tau proteins. These proteins build up in the brains of patients with Alzheimer's and are thought to slowly destroy brain cells and the connections between them.

The brains from patients who had Alzheimer's in this study had significant levels of tau tangles in these three brain regions, compared to the brains from people without the disease. What's more, in these three brain regions, people with Alzheimer's had lost up to 75% of their neurons.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It's remarkable because it's not just a single brain nucleus that's degenerating, but the whole wakefulness-promoting network," lead author Jun Oh, a research associate at UCSF, said in the statement. "This means that the brain has no way to compensate, because all of these functionally related cell types are being destroyed at the same time."

The researchers also compared the brains from people with Alzheimer's with tissue samples from seven people who had two other forms of dementia caused by the accumulation of tau: progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal disease. Results showed that despite the buildup of tau, these brains did not show damage to the neurons that promote wakefulness.

"It seems that the wakefulness-promoting network is particularly vulnerable in Alzheimer's disease," Oh said in the statement. "Understanding why this is the case is something we need to follow up in future research."

Though amyloid proteins, and the plaques that they form, have been the major target in several clinical trials of potential Alzheimer's treatments, increasing evidence suggests that tau proteins play a more direct role in promoting symptoms of the disease, according to the statement.

The new findings suggest that "we need to be much more focused on understanding the early stages of tau accumulation in these brain areas in our ongoing search for Alzheimer's treatments," senior author Dr. Lea Grinberg, an associate professor of neurology and pathology at the UCSF Memory and Aging Center, said in the statement.

The findings were published Monday (Aug. 12) in Alzheimer's & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association.

- 9 Surprising Risk Factors for Dementia

- 7 Ways the Mind and Body Change with Age

- 6 Fun Ways to Sharpen Your Memory

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.