New Alzheimer's drug slightly slows cognitive decline. Experts say it's not a silver bullet.

Experts weigh in on whether the newly approved Alzheimer's treatment lecanemab is worth taking.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved the second-ever drug in a new class of medications designed to treat Alzheimer's disease.

The drug — lecanemab (brand name Leqembi) — underwent "accelerated approval," which differs from the FDA's standard approval process where drugmakers have to provide direct evidence of a drug's clinical benefit. That said, late-stage trials do suggest that lecanemab slightly slows the rate of cognitive decline when taken in early stages of the disease.

Although sometimes heralded as a "breakthrough" in news coverage, lecanemab has garnered a mixed review from doctors and scientists because of its modest effectiveness and potential side effects, as well as its price tag. Live Science asked experts what they think about lecanemab and what patients should know about the treatment.

"Some people in the field see this as a watershed moment," Dr. Michael Greicius, a professor of neurology at Stanford Medicine, told Live Science in an email. "Others, like myself, do not."

Related: Brain 'pacemaker' for Alzheimer's shows promise in slowing decline

How does lecanemab work?

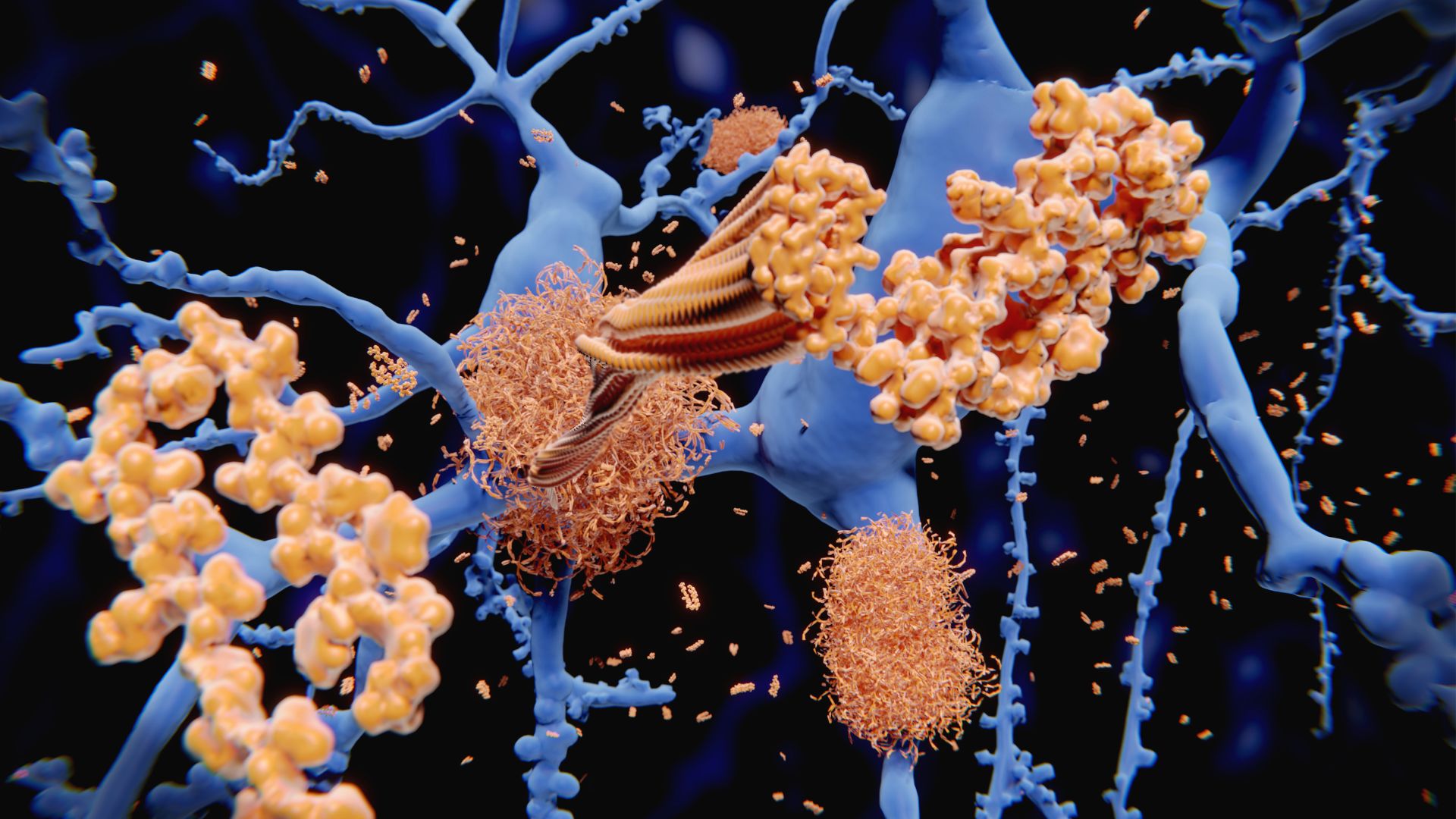

Lecanemab, developed by the pharmaceutical companies Eisai and Biogen, is an engineered antibody that's delivered via IV infusion. The antibody latches onto sticky clumps of protein, called amyloid-beta plaques, that accumulate in the brain and in the fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. Once bound, the antibody instructs the immune system to destroy those clumps. Amyloid-beta plaques are a hallmark of Alzheimer's, and for many years, most scientists thought these plaques were the root cause of the disease.

Proponents of the so-called amyloid hypothesis theorize that a buildup of these plaques sets off a chain reaction that eventually kills brain cells involved in thinking and memory. This idea dominated Alzheimer's research for decades, but it's since been challenged by evidence that amyloid plaques are just one piece of a very complicated puzzle, according to a 2018 review in the journal Frontiers in Neuroscience.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While the debate surrounding the amyloid hypothesis remains unsettled, the FDA has now approved two drugs that take aim at amyloid-beta plaques. Another anti-amyloid antibody drug, aducanumab (brand name Aduhelm), was approved in 2021. The big question is, do these drugs offer clear benefits to patients?

Is lecanemab effective?

Prior to the approval of aducanumab and lecanemab, drugs called cholinesterase inhibitors and NMDA antagonists were approved to alleviate some of the cognitive and behavioral symptoms of Alzheimer's, according to the National Institute on Aging. These drugs don't target the root cause of the disease, but they can be helpful for managing its effects.

Aducanumab marked the first "disease-modifying" drug approved for Alzheimer's — meaning it directly tackles what scientists believe is a cause of the illness. But its approval stirred controversy because there wasn't strong evidence to suggest it slowed cognitive decline, and the FDA's advisory committee actually recommended that the drug not be approved, according to Nature.

The FDA approved lecanemab on the basis of a mid-stage trial, which showed the drug cleared amyloid but didn't evaluate whether it slowed cognitive decline. However, the results of a larger, late-stage trial were released in November 2022 and offer evidence that the treatment slows cognitive decline "but debatable evidence that it is clinically impactful," said Dr. Constantine Lyketsos, the Elizabeth Plank Althouse professor for Alzheimer's research at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

The 18-month trial included about 1,800 people with early Alzheimer’s disease ages 50 to 90, according to a Jan. 5 report in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). Half of the participants received twice-monthly infusions of lecanemab, while the other half received a placebo. Cognitive decline was tracked using the Clinical Dementia Rating-Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB), a 18-point scale where higher numbers indicate worse dementia. After 18 months, the lecanemab group showed a significant decrease in amyloid in the brain, compared with the placebo group. Meanwhile, their CDR-SB scores had increased 1.21 points, while the placebo group's increased 1.66 points, meaning the final scores differed by 0.45 points.

Industry experts have argued that, "for a physician to notice a difference in a patient over 1 years' time the patient needs to decline by at least 1 full point on the CDR-SB," Greicius said. In other words, a difference of 0.45 points might not be noticeable to a doctor, let alone the patient or their caregivers, he told Live Science.

That said, given the limited length of the clinical trials, we don't yet know if patients who take the drug for longer than 18 months will see cumulative benefits or what the course of disease might look like after patients cease treatment, the NEJM report noted.

When doctors are speaking with patients about the potential benefits of lecanemab, "it's really down to making sure patients understand how little they can expect," Lyketsos told Live Science. "Until we see a robust effect, I think most people are going to opt out."

What are the potential side effects of lecanemab?

In the late-stage trial, about 26% of the lecanemab group had infusion-related reactions, which included flu-like symptoms, nausea, vomiting and changes in blood pressure, compared with only 7% of the placebo group.

Trial participants also experienced amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), structural abnormalities that appear on brain scans and have previously been linked to anti-amyloid antibodies. Of the treated group, 17% had ARIA with bleeding in or on the brain, and nearly 13% had ARIA with brain swelling; that's compared with about 9% and 2% of the placebo group, respectively. Most cases were asymptomatic and resolved on their own, although people sometimes reported symptoms such as headache, visual disturbances, confusion and dizziness.

The FDA mandated that lecanemab's label carry a warning for this side effect and that doctors monitor patients closely for it. "ARIA usually does not have symptoms, although serious and life-threatening events" — like seizures — "rarely may occur," the FDA stated.

Some evidence suggests that such fatal events may have taken place during the extension phase of trial, in which all trial participants can opt to take the drug, open-label, according to documents obtained by STAT and Science. These records show that three participants died of severe brain bleeding, swelling and seizures after starting to receive the drug during the extension phase; it's unclear whether these participants were previously in the treatment or placebo arm of the study.

Sources told STAT and Science that they suspect the deaths may be related to ARIA and that lecanemab, in clearing amyloid from the brain, also may have weakened the patients' blood vessels. Eisai attributed two of the deaths to factors unrelated to lecanemab and declined to comment on the third death, Science reported in December 2022. In a written statement to Science, an Eisai spokesperson said "all serious events, including fatalities," are provided to the FDA and other regulatory bodies.

In two of the cases, blood thinners may have worsened patients' bleeding, Science reported. "Personally, I think that someone on blood thinners should not go on these therapies for now," Lyketsos said, citing these cases.

"I think ARIA can be fairly safely managed by dementia specialists in the tightly controlled setting of a clinical trial," Greicius said. "I am very concerned that if and when lecanemab hits the real world of clinical practice, safety monitoring will, invariably, be less rigorous, which will result in more patient deaths."

Is lecanemab worth the cost?

A year's course of lecanemab will cost an estimated $26,500 per year, although the "actual annualized pricing may vary by patient," according to a statement from Eisai.

"That's just the cost of the drug," Lyketsos said, not the cost of the actual infusions, regular brain scans needed to check for ARIA, or the initial tests run to confirm the presence of plaques in a patient's brain. "We're talking a whole lot more [than $26,500]," Lyketsos said.

And currently, Medicare covers lecanemab only in the context of approved clinical trials; the same policy applies to aducanumab, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

That's because these drugs were granted accelerated approval, which only requires that drugs show a specific, measurable effect on the body, not that they improve a clinical endpoint, such as time to death or disability. Both aducanumab and lecanemab clear amyloid from the brain, but to earn accelerated approval, they didn't have to show they helped people stay sharp longer.

Only if lecanemab earns standard FDA approval would Medicare provide broader coverage for the drug, CMS has stated.

This article is for informational purposes only, and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.