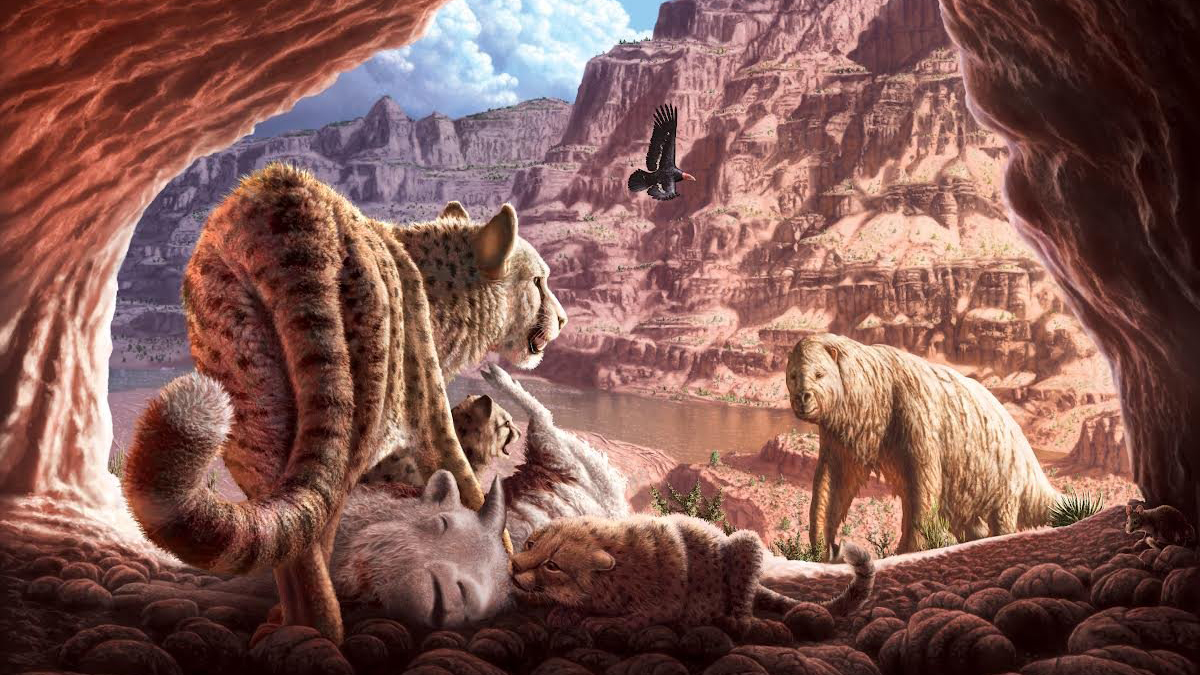

20,000 years ago, two American cheetahs fought to the death in a Grand Canyon cave

The extinct cat may have been more like modern snow leopards than today's African cheetahs.

Some 20,000 years ago in a cave in a cliff wall in the Grand Canyon, two American cheetahs battled tooth against claw. The victor is lost to history, but one of the big cats, a juvenile that was bitten through the spine, likely died where it fell on the cave floor, leaving behind bones and bits of mummified tissue.

Now, the remains of this unfortunate feline, along with fossils from two other Grand Canyon caves, have revealed that the extinct American cheetah (Miracinonyx trumani) may not have been swift flatland sprinters like Africa's modern cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus). Instead, these cats may have been more like today's snow leopards (Panthera uncia), prowling cliff sides and rocky regions and eating mostly mountain goats and bighorn sheep.

Scientists found the fossils decades ago and they identified the bones at the time as belonging to mountain lions (Puma concolor). But recent re-analysis of the bones revealed that they instead belong to the American cheetah, which is known from other fossil sites. American cheetahs were closely related to mountain lions, but had the short snout and slim proportions of today's African cheetahs.

Cliffside kitties

The American cheetah has been extinct for about 10,000 years. Before the end of the last Ice Age, it lived across North America — its bones have been found from West Virginia to Arizona, and as far north as Wyoming. The speed of this extinct cat is thought to explain why modern pronghorn antelopes (Antilocapra americana) can run at 60 mph (96.5 km/h). None of the pronghorn's living predators sprint that fast, but the American cheetah probably could.

But the new research suggests that American cheetahs didn't primarily hunt pronghorns — or at least, not exclusively. While some cheetah fossils have been found in open-range valleys where ancient pronghorns roamed, many other such fossils were discovered in rocky, steep spots, where caves provided cozy dens, said John-Paul Hodnett, a paleontologist at the Maryland-National Capital Parks and Planning Commission and lead author of the study that reexamined the Grand Canyon specimens.

Related: Did cats really disappear from North America for 7 million years?

Hodnett first encountered the fossils nearly 20 years ago, as an undergraduate student at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, he told Live Science. A graduate student that Hodnett worked with at the time was identifying fossils from Rampart Cave, a small, low chamber in the western Grand Canyon that was carpeted with fossil bones and layers of fossilized giant sloth poop.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Among the cataloged fossils were some that had been labeled as belonging to mountain lions. But Hodnett, who had been studying American cheetah fossils from southern Arizona, recognized that the bones were actually those of a cheetah. Hodnett's advisor arranged access to a handful of additional "mountain lion" bones from two other Grand Canyon caves: Next Door Cave in the central Grand Canyon and Stanton's Cave in the eastern Grand Canyon. Those bones also turned out to belong to American cheetahs and not mountain lions, Hodnett found. There are certain features in the bones, like the shape of an ankle structure, that can distinguish cheetahs from mountain lions, and some of their bones are different sizes, Hodnett said.

A prehistoric cat fight

Busy with other research and projects, Hodnett put this discovery aside for years without publishing what he'd learned. But in 2019, he and his colleagues were working on an inventory of the known fossil record in Grand Canyon National Park, which spurred him to pull out and update his American cheetah research.

The bone from Next Door Cave was a heel bone, while Stanton's Cave held a portion of a paw with an intact claw sheath. The most intriguing finds came from Rampart Cave and represented two American cheetah individuals. One was a subadult — the feline equivalent of a teenager — while the other was a kitten about six months of age, Hodnett said. The young adult had been attacked, with puncture wounds on the skull and spine that were about the size of an adult American cheetah's teeth. These wounds were likely fatal.

"You see a very sharp puncture in the spine and that would have been debilitating right off the bat," Hodnett said. "It does not look healed at all."

It's unclear if the two young cats in the cave were related, but some semi-mummified soft tissue still clings to the bones, so researchers might be able to recover and analyze enough DNA to find that out, Hodnett said. The wounds could be the result of a territorial battle, he added. Or perhaps a male cheetah was trying to kill another's young, a behavior seen today in African lions.

Whatever the case, the finds reveal that American cheetahs hunted beyond the grasslands. Cheetah fossils found in caves are often associated with the bones of bighorn sheep and an extinct herbivore known as Harrington's mountain goat (Oreamnos harringtoni). This suggests that these cliff-dwellers may have been prime American cheetah prey.

"This discovery, or reidentification, of these classically-called 'mountain lion' fossils gives us the idea that this particular extinct cat, Miracinonyx, may have been a little bit more diverse in terms of its preferred ecology," Hodnett said.

The findings were published in the May issue of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.