'Longitude' Prize Will Tackle Antibiotic Resistance

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

The British public voted for the £10m Longitude Prize to go towards funding scientific research to solve the urgent global problem of rising resistance to antibiotics.

The problem of bacterial resistance threatens to return us to a pre-penicillin age in which minor diseases and operations can kill us. The choice of this problem triumphed over important issues such as securing resources of food or water for the majority of the world’s population. It is sobering to learn that, because private pharmaceutical companies do not see sufficient profit in researching and developing new antibiotics, the money for the prize derives instead from National Lottery funds.

The longitude problem

The original and ground-breaking “Longitude Reward” of £10,000 (about £1.2m in today’s money) was put up by the British government exactly 300 years ago in 1714. So why was “the problem of longitude” as big a deal as antibiotics are today? Like bacterial resistance it was literally a global problem, but not for all of humanity. Powerful European states like Britain, France, Spain and the Netherlands were competing to expand their empires and colonies and to increase international trade. Success depended on prowess in navigation, as naval captains charted courses to reach their desired port and to avoid ship-wrecking obstacles. These goals depended on knowing your exact place on the Earth’s globe, in latitude and longitude, at sea and out of sight of land.

Navigators had long known how to find their latitude using astronomy. It was readily calculable from observations of the altitudes of the sun by day, or the pole star by night, which changed in a regular way as you sailed north or south from the Earth’s poles. The problem of longitude was that, for places with similar latitudes, such Athens, Lisbon, New York and San Francisco, the stars rise and set in the same way, with the same altitudes, but at different times relative to your home port. For example, an observer in New York sees the sun rise, culminate and set in the same way as an observer in Lisbon but five hours later, because of the difference in longitude of 25 degrees, or a distance of 5,000km.

So how could a Portuguese navigator approaching the shallows of New York, with astronomical tables compiled for Lisbon, know from the stars that he was now 5,000km or 25 degrees of latitude west of his home port? For several decades before 1714 scientists had known that the best solution was to have a clock on board that kept the time of the home port, Lisbon for example. Unfortunately, no-one could make a clock that kept very good time at sea, given the tossing of the ship and the corrosion of salty sea spray.

The entrepreneurial spirit

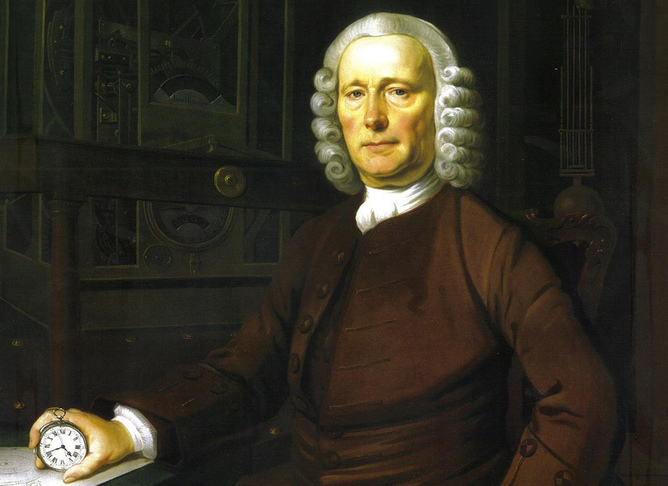

The first such clocks were designed by the ultimate winner of the “Longitude Reward”, the self-taught and entrepreneurial Yorkshire clockmaker, John Harrison. The story of Harrison’s success, and the belated, somewhat grudging award of the money in the 1760s by the Board of Longitude, has been told by Dava Sobel in her popular book Longitude.

But her book does not tell the whole story, and experts are now developing alternative perspectives, which ask whether state-funded research had a place alongside entrepreneurial individuals. For example, Harrison’s clocks were very expensive and until a simpler, mass-produced mechanism was developed, the Royal Navy could only provide them for a few of its ships. Instead, most naval vessels used very accurate astronomical tables rather than Harrison’s chronometers to find their longitude well into the 19th century.

When the Admiralty (essentially the state) first offered its reward in 1714, a very different solution to “the longitude problem” looked promising. It involved Admiralty co-ordination of worldwide observations of magnetic compass data. Sir Isaac Newton’s colleague Edmund Halley was a proponent of a magnetic solution. Earlier 17th-century versions of the Longitude Prize had also expected that compass data would solve the problem, although they ultimately failed to do so. In Latitude, my popular history of science, I recounted these earlier, magnetic attempts to solve the longitude problem.

The history of science records lots of promising, well-tried but ultimately dead ends, as well as unexpected new directions. It also highlights contrasting styles of research – for example the state-sponsored collaboration preferred by the Board of Longitude versus that of entrepreneurial individuals such as Harrison. Recent research on the human genome reveals similar contrasts between private and public research programmes.

What kind of scientific research will win the 2014 Longitude Prize for the defeat of bacteria? Unfortunately I don’t have a crystal ball, but I predict that it will more likely be a collective with state funding than an individual like Harrison.

Stephen Pumfrey does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Why is yawning contagious?

Scientific consensus shows race is a human invention, not biological reality