The deadliest viruses in history

These are the 12 most lethal viruses, based on their mortality rates or the number of people they have killed.

Humans have been fighting viruses since the species has existed. For some viral diseases, vaccines and antiviral drugs have prevented widespread infection or helped people recover. And we've even been able to eradicate one disease — smallpox.

Some viruses pose a bigger threat than others. The viral strain that drove the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa kills up to 90% of the people it infects, making it the most lethal member of the Ebola family.

Related: 20 of the worst epidemics and pandemics in history

But there are other viruses that are are even deadlier. Some viruses, including the novel coronavirus currently driving outbreaks around the globe, have lower fatality rates, but still pose a serious threat to public health because they infect so many people.

Here are the 12 worst killers, based on the likelihood that a person will die if they are infected with one of them, the sheer numbers of people they have killed and whether they represent a growing threat.

Marburg virus

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the Marburg virus was first identified by scientists in 1967, when small outbreaks occurred among lab workers in Germany who were exposed to infected monkeys imported from Uganda. Marburg virus symptoms are similar to Ebola in that both viruses can cause hemorrhagic fever, meaning that infected people develop high fevers, and bleeding throughout the body that can lead to shock, organ failure and death, according to Mayo Clinic.

The case fatality rate in the first outbreak (1967) was 24%, but it was 83% in the 1998-2000 outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and 100% in the 2017 outbreak in Uganda, according to the WHO.

The first known Marburg virus outbreak in West Africa was confirmed in August 2021. The case was a male from south-western Guinea, who developed a fever, headache, fatigue, abdominal pain and gingival hemorrhage before ultimately dying of the disease. This outbreak lasted for six weeks and, while there were 170 high-risk contacts, only one case was confirmed, according to Reuters.

Ebola virus

In 1976, the first known Ebola outbreaks in humans struck simultaneously in the Republic of the Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Ebola is spread through contact with blood or other body fluids, or tissue from infected people or animals. The known strains vary dramatically in their deadliness, Dr. Elke Muhlberger, an Ebola virus expert and associate professor of microbiology at Boston University, told Live Science.

One strain, Ebola Reston, doesn't even make people sick, though it is deadly to other primates, according to Essential Human Virology (2016). But for the Bundibugyo strain, the human fatality rate is up to 25%, and it is up to 90% for the Zaire strain.

The largest Ebola outbreak on record emerged in West Africa in early 2014 and took two years to resolve. During that time, it infected 28,652 people and claimed 11,325 lives, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Transmission (CDC).

In December 2020, the Ervebo vaccine was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. This vaccine helps to defend against the Zaire ebola virus and a global stockpile became available from January 2021.

Dr. Elke Mühlberger is a professor of microbiology and the director of Integrated Science Services at the National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories (NEIDL) at Boston University.

Dr. Mühlberger is a renowned expert in the field of BSL-4 hemorrhagic fever viruses. She has a strong research focus on the highly pathogenic filoviruses, Ebola and Marburg virus. She received her PhD in Virology from the Philipps University Marburg, Marburg, Germany in 1993 and continued to work on filoviruses as an independent PI and group leader in Marburg. In 2008, she joined the Department of Microbiology at Boston University.

Rabies

Although rabies vaccines for pets, which were introduced in the 1920s, helped to make the disease extremely rare in the developed world, this condition remains a serious problem in India and parts of Africa. About 59,000 people die every year from the virus, according to a 2019 study in the CDC's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Infection from this virus develops after a bite or scratch from an infected mammal. Once a person is bitten, they must immediately get rabies vaccines or antibody treatments to prevent the disease from progressing. If they don't, the virus will damage the brain and nerves. Once symptoms begin to show, death almost always follows; the virus has a 99% fatality rate, according to the CDC.

"It destroys the brain, it's a really, really bad disease," Muhlberger said. "We have a vaccine against rabies, and we have antibodies that work against rabies, so if someone gets bitten by a rabid animal we can treat this person," she said.

However, she said, "if you don't get treatment, there's a 100% possibility you will die."

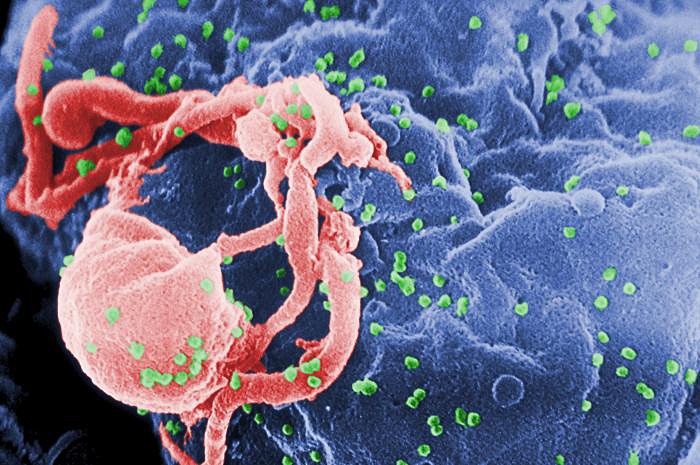

HIV

In the modern world, the deadliest virus of all may be HIV.

"It is still the one that is the biggest killer," Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease physician and spokesman for the Infectious Disease Society of America told Live Science.

An estimated 32 million people have died from HIV since the disease was first recognized in the early 1980s. "The infectious disease that takes the biggest toll on mankind right now is HIV," Adalja said.

Powerful antiviral drugs have made it possible for people to live for years with HIV. And in rare cases, stem cell transplants have cured the disease. But the disease continues to devastate many low- and middle-income countries, where 95% of new HIV infections occur.

Nearly 1 in every 25 adults within the World Health Organization Africa region is HIV-positive, meaning that there are over two-thirds of the people living with HIV worldwide, according to the WHO. In 2021, there were 650,000 HIV-related deaths worldwide.

Dr. Amesh Adalja is an infectious disease physician specialising in emerging infectious diseases, pandemic preparedness, and biosecurity. A Senior Scholar at the Center for Health Security at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland in the United States of America (USA), he is also a spokesman for the Infectious Disease Society of America.

A fellow of the American College of Physicians, and the American College of Emergency Physicians, he obtained a Bachelor of Science degree in industrial management from Carnegie Mellon University in 1995 and graduated from the American University of the Caribbean School of Medicine in 2002.

Smallpox

In 1980, the World Health Assembly declared the world free of smallpox. But before that, humans had battled smallpox for thousands of years, and the more severe version of the disease, Variola major, killed about 30% of those it infected, according to the WHO. It left survivors with deep, permanent scars and, often, blindness.

In populations outside of Europe, where people had little contact with the virus before visitors brought it to their regions, mortality rates were much higher. For example, historians estimate that smallpox, which was introduced by European explorers, killed 90% of the native population of the Americas. In the 20th century alone, smallpox killed 300 million people, according to National Geographic.

"It was something that had a huge burden on the planet, not just death but also blindness, and that's what spurred the campaign to eradicate from the Earth," Adalja said.

Hantavirus

Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) is a deadly disease for those who contract it, but it has killed relatively few people. It first gained wide attention in the U.S. in 1993, according to the CDC). A healthy, young Navajo man and his fiancée living in the Four Corners area of the United States died within days of developing shortness of breath. A few months later, health authorities isolated hantavirus from a deer mouse living in the home of one of the infected people. More than 833 people in the U.S. have contracted HPS as of the end of 2020, the last year that data was reported for, and 35% have died from the disease, according to the CDC.

The virus is not transmitted from one person to another, rather, people contract the disease from exposure to the droppings of infected mice.

Previously, a different hantavirus, called Korean hemorrhagic fever, caused an outbreak in the early 1950s, during the Korean War, according to a 2010 paper in the journal Clinical Microbiology Reviews. More than 3,000 United Nations troops became infected, and about 12% of them died.

While the virus was new to Western medicine when it was discovered in the U.S., researchers realized later that Navajo medical traditions describe a similar illness, and linked the disease to mice.

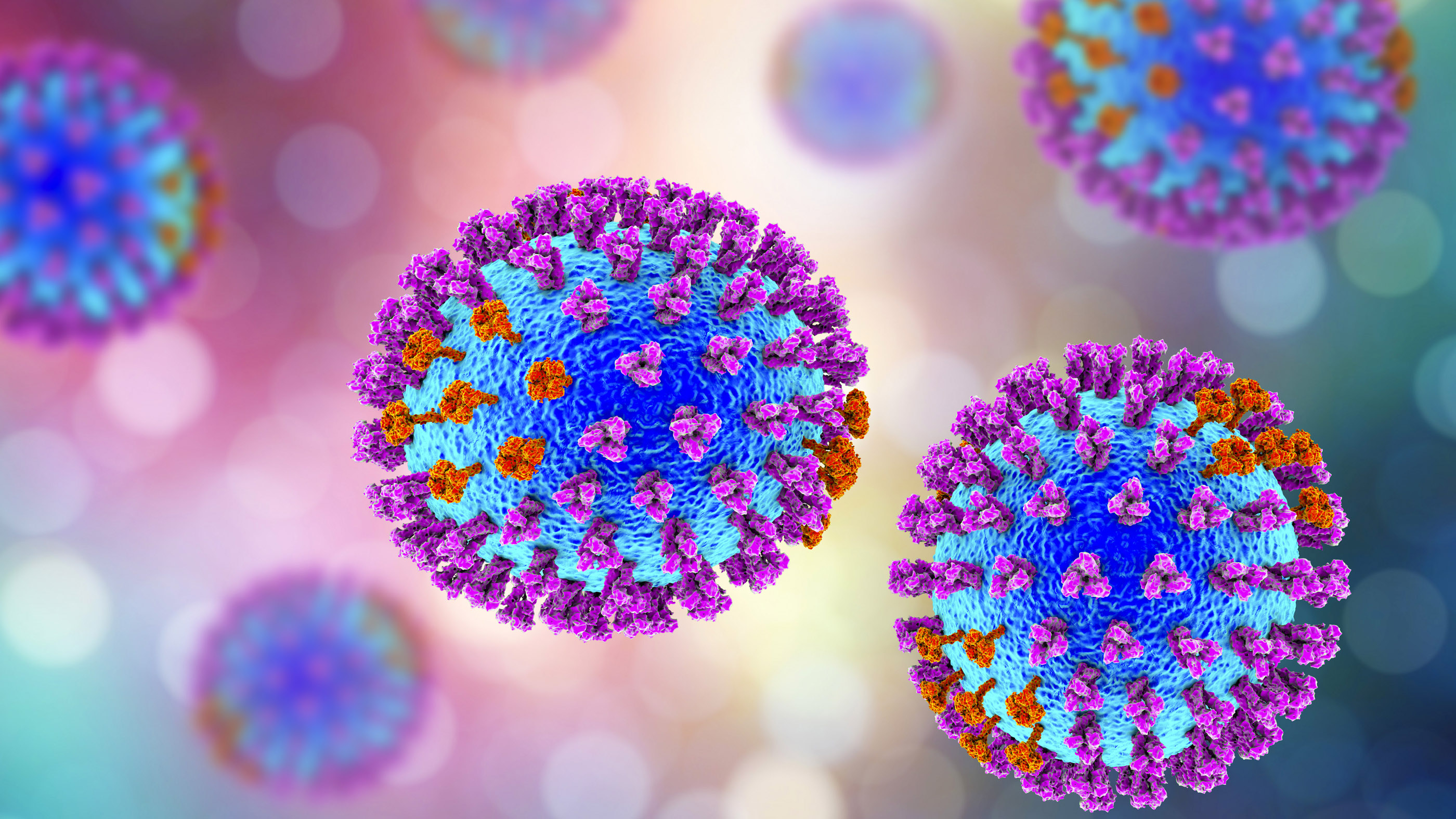

Influenza

Influenza kills a small proportion of the people it infects, at about 1.8 in 100,000 people every year, according to the CDC. But because it infects so many people, it's one of the leading killers worldwide. During a typical flu season, up to 650,000 people worldwide will die from the illness, according to WHO.

And occasionally, a new flu strain emerges, and a pandemic spreads across the globe. Often, these new strains have higher mortality rates than endemic flu.

The most deadly flu pandemic, sometimes called the Spanish flu, began in 1918 and sickened up to 40% of the world's population, killing an estimated 50 million people, according to CDC.

"I think that it is possible that something like the 1918 flu outbreak could occur again," Muhlberger said. "If a new influenza strain found its way in the human population, and could be transmitted easily between humans, and caused severe illness, we would have a big problem."

Dengue

Dengue hemorrhagic fever, caused by the dengue virus, is a mosquito-borne disease that first appeared in the 1950s in the Philippines and Thailand. It has since spread throughout the tropical and subtropical regions of the globe, according to a 2009 study in the journal Clinical Microbiology Reviews. Up to 40% of the world's population now lives in areas where dengue is endemic and the disease will spread farther as climate change enables the mosquitoes that carry it to spread to other regions, according to the journal Nature .

According to WHO, dengue infects 100 to 400 million people a year. Although dengue fever has a lower mortality rate than some other viruses, at around 1%, the virus can cause an Ebola-like disease called dengue hemorrhagic fever, which has a mortality rate of 20% if left untreated. "We really need to think more about dengue virus because it is a real threat to us," Muhlberger said.

A vaccine for dengue, called Dengvaxia was approved in 2019 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in children ages 9 to16 years old living in areas where dengue is common and with a confirmed history of virus infection, according to the CDC. In some countries, an approved vaccine is available for those who are 9 to 45 years old, but again, recipients must have contracted a confirmed case of dengue in the past. Those who have not caught the virus before could be put at risk of developing severe dengue if given the vaccine.

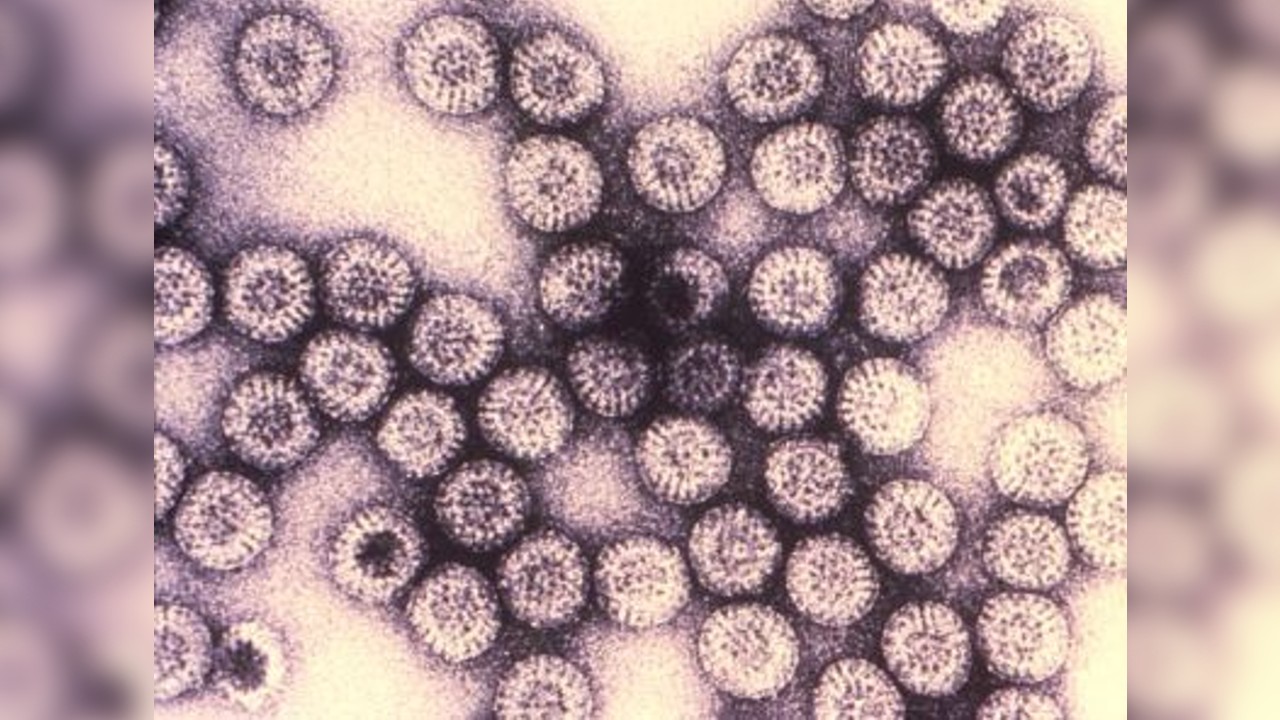

Rotavirus

Rotavirus is a diarrheal disease that kills about 200,000 children annually, mostly in Nigeria and India, according to PreventRotavirus, a council dedicated to widespread use of rotavirus vaccines.

The virus can spread rapidly, through what researchers call the fecal-oral route (meaning that small particles of feces end up being consumed).

Thanks to vaccines, children in the developed world rarely die from the infection. But the disease is a killer in the developing world, where rehydration treatments are not widely available.

The WHO estimates that worldwide, there are more than 25 million outpatient visits and two million hospitalizations each year due to rotavirus infections. Countries that have introduced the vaccine have reported sharp declines in rotavirus hospitalizations and deaths.

Two vaccines are now available to protect children from rotavirus, the leading cause of severe diarrheal illness among babies and young children.

SARS-CoV

The virus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, was first identified in 2003 during an outbreak in China, according to the WHO. The virus likely emerged in bats initially, then hopped into nocturnal mammals called civets before finally infecting humans, according to the Journal of Virology. After triggering an outbreak in China, SARS spread to 26 countries around the world, infecting 8,096 people and killing more than 774 over the course of several months, according to the CDC.

The disease causes fever, chills and body aches, and often progresses to pneumonia, a severe condition in which the lungs become inflamed and fill with pus. SARS has an estimated mortality rate of 9.6%, however, no new cases of SARS have been reported since the early 2000s, according to the CDC.

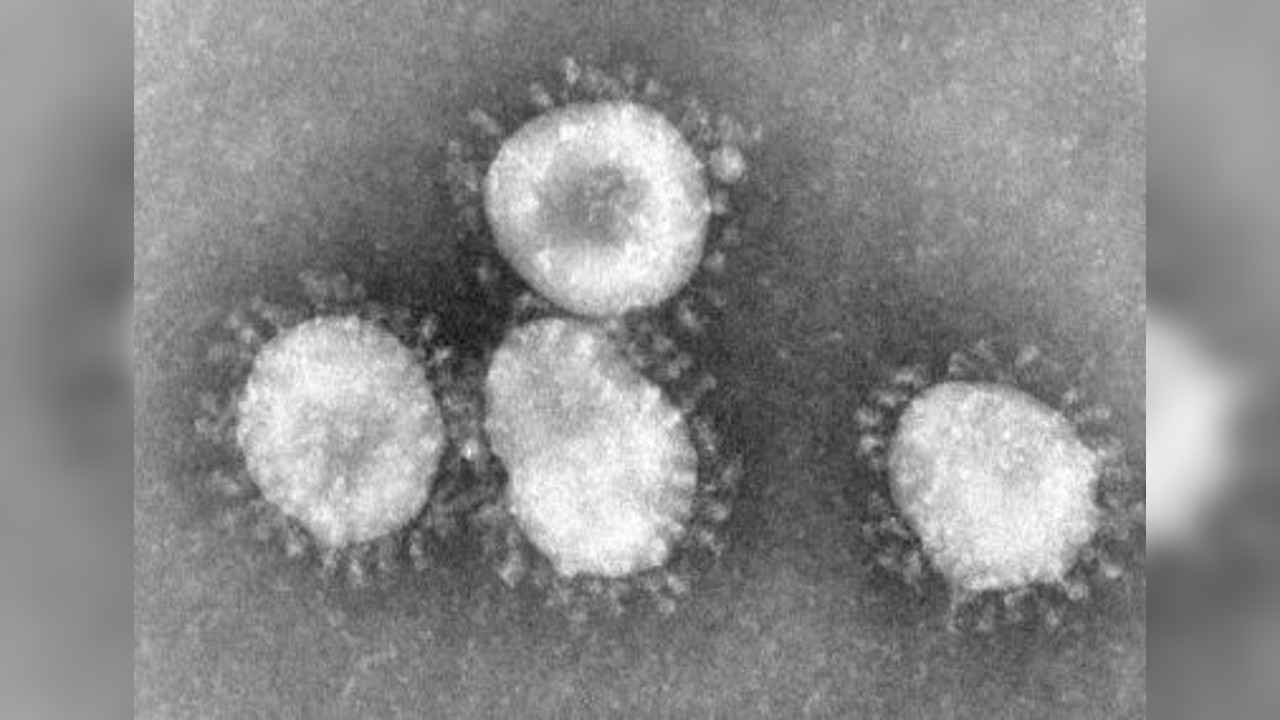

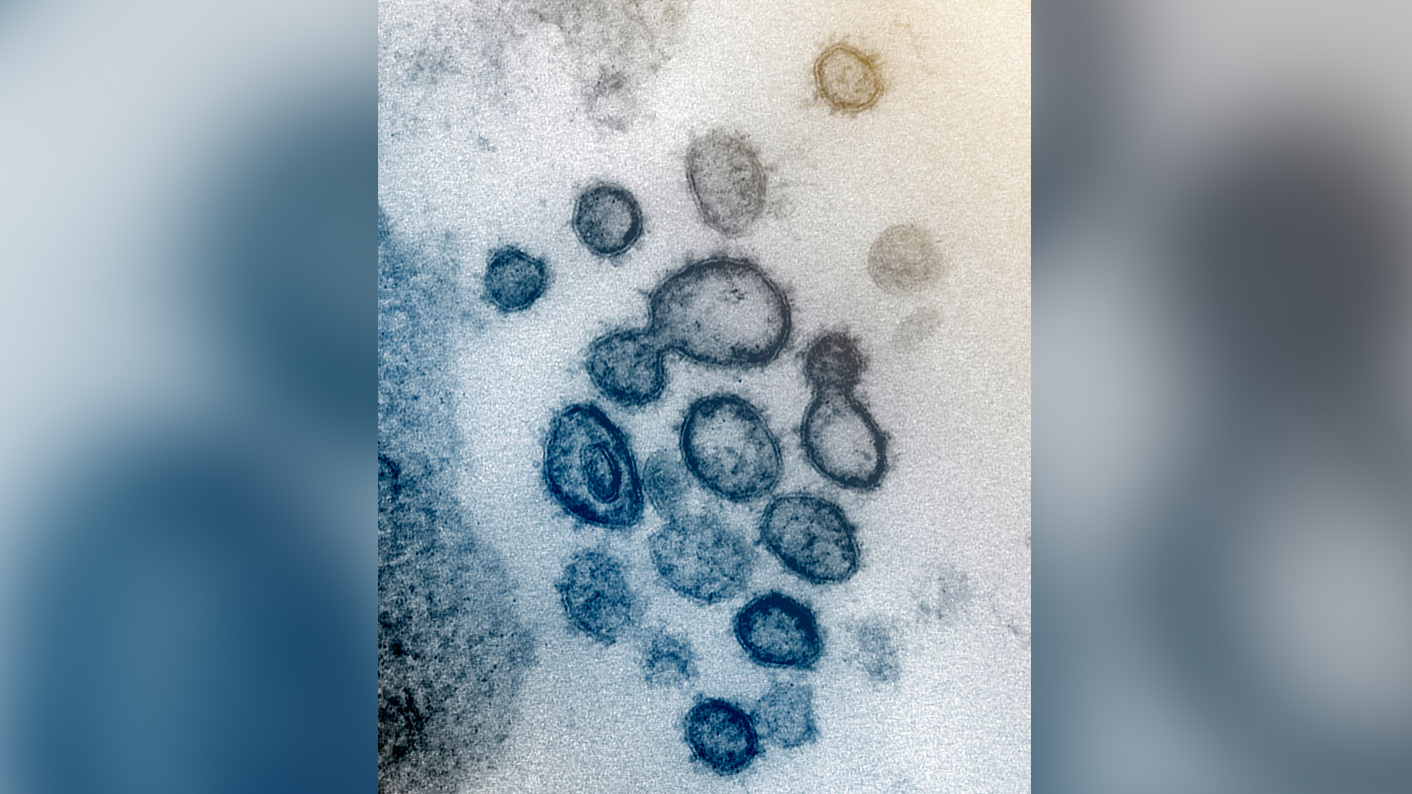

SARS-CoV-2

SARS-CoV-2 may not kill a huge fraction of the people it infects, but the disease caused by the virus, called COVID-19, has become the leading viral cause of death in since it exploded onto the scene in 2020. As of October 2022, the virus has caused more than 6.57 million deaths worldwide and counting, and has infected at least 626 million people, according to OurWorldInData.

SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the same large family of viruses as SARS-CoV, known as coronaviruses, and was first identified in December 2019 in the Chinese city of Wuhan. The virus may have originated in bats and passed through an intermediate animal before infecting people, according to a 2021 study in the journal Nature.

The initial outbreak prompted an extensive quarantine of Wuhan and nearby cities, restrictions on travel to and from affected countries and a worldwide effort to develop diagnostics, treatments and vaccines.

Estimating an infection fatality rate, or the fraction of people who die after being infected, is difficult, because many mild cases are never diagnosed. But age is clearly a huge factor in the virus' lethality: One study in the journal The Lancet estimated that the virus killed about 0.0023% of children under age 7 that it infected and about 20% of those infected over age 90.

The virus also poses a higher risk to people who have underlying health conditions such as diabetes, high blood pressure or obesity, according to WHO. Common symptoms include fever, cough, loss of taste or smell and shortness of breath and more serious symptoms include breathing difficulties, chest pain and loss of mobility.

Several COVID-19 vaccines, as well as booster doses for those vaccines, are currently approved for use in both children and adults. These vaccines dramatically reduce the odds of severe disease and death, according to the CDC.

MERS-CoV

The virus that causes Middle East respiratory syndrome, or MERS, sparked an outbreak in Saudi Arabia in 2012 and another in South Korea in 2015. It has a high case fatality rate, killing about 35% of people diagnosed with it. But the virus has killed only 858 people as of 2021, because it does not spread easily between people.

The MERS virus belongs to the same family of viruses as SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. According to WHO, the disease infected camels before passing into humans and can trigger a fever, coughing and shortness of breath in infected people.

MERS is deadly because, like its less lethal cousins SARS and SARS-CoV-2, it often progresses to severe pneumonia. There is no vaccine available to prevent this disease. The best way to reduce the chances of infection is to wash hands regularly, avoid contact with camels and not consume products containing raw animal milk.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.