Aboriginal memory technique may work better than Sherlock's 'memory palace'

Linking information to a narrative and a place may help memory more than linking information to a place alone.

An ancient memory technique developed by Aboriginal Australians may work better than the "mind palace" invented in ancient Greece and popularized by the BBC version of Sherlock Holmes.

Both methods involve mentally attaching information to a physical object or location, but the Aboriginal technique adds a storytelling component. Researchers aren't sure if it's the narrative element or some other aspect that seemed to boost the Aboriginal technique's effectiveness, and the study is small. But the research highlights that cultures put in a lot of effort in order to pass along information without modern-day technology or even writing.

Related: 6 fun ways to sharpen your memory

"There's a certain satisfaction in knowing how to learn these things," said study co-author David Reser, a lecturer at the Monash University School of Rural Health in Australia.

Building memories

The "mind palace" is a method of remembering that attaches information to objects inside an imaginary building or room; also known as the method of loci, the technique is said to have originated when the Greek poet Simonides of Ceos narrowly avoided being crushed in a building collapse during a crowded banquet. Simonides was able to identify the bodies of his fellow revelers by remembering where they'd been sitting before he stepped out of the room, illustrating the value of attaching memories to a physical location — even if just in the mind. The character of Holmes uses the technique to help him crack cases in the BBC series "Sherlock," which aired between 2010 and 2017. Research on the mind palace technique shows that it boosts both short- and long-term memory.

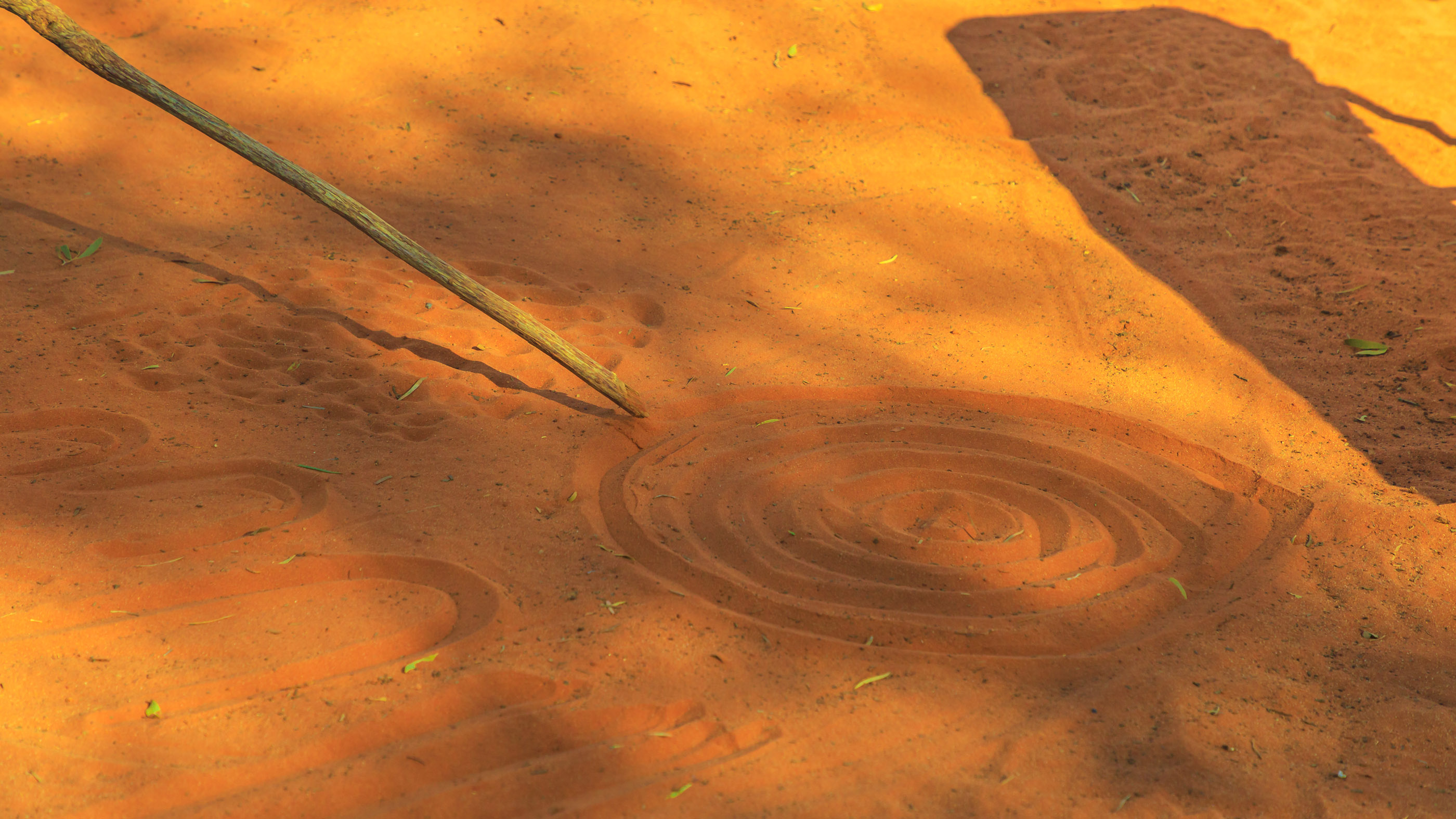

A new study tests the mind palace technique against the one used by untold generations of Aborigines. This technique also attaches information to physical geography, but in the form of a narrative that incorporates landmarks, flora and fauna. The idea to compare the two arose when Reser and a fellow lecturer, Tyson Yunkaporta, were chatting about memory and ways to incorporate Indigenous culture into the medical school curriculum. Yunkaporta, now at Deakin University in Victoria, Australia, is a member of the Apalech Clan and author of "Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World" (HarperOne, 2020).

Along with other colleagues and medical students, Yunkaporta and Reser put together a study of the two techniques, drawing from first-year medical students at the university during their very first days of classes. Seventy-six students participated. They were first shown a list of 20 common butterfly names — chosen specifically because the researchers wanted the study to have nothing to do with medicine — and given 10 minutes to memorize the list. They were then told to write down as many of the names as they could remember.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Next came a 30-minute session during which a third of the students were taught the "memory palace" technique, and a third were taken to a garden on campus, where Yunkaporta walked them through the Aboriginal technique and developed a story attached to the garden for memorizing the butterfly list. The final third, a control group, watched an unrelated video during this time.

The students were again given the list and 10 minutes to memorize; then they were asked to write down the butterfly names again. After a 20-minute unstructured break, they were tested for a third and final time.

Incorporating a narrative

All of the students improved over the tests, simply because they had seen the list several times. The memory palace technique improved the total percentage of the 20 names that the students remembered by a moderate amount, with the Aboriginal technique showing a strong effect. This translated to only one or two extra names, though, as the test turned out to be a little too easy for the eager medical students — many remembered 20 out of 20 butterfly names on the first try, without any training at all, Reser said. A future study with medical school students would need to be more challenging, he said.

"By the time someone gets into medical school they probably have developed some pretty sophisticated techniques themselves," he said.

However, other ways of looking at the memory training also showed improvements with the Aboriginal technique compared to the mind palace. The chances that a student would improve from remembering fewer than 20 of the names to 20 out of 20 on later tests tripled in the Aboriginal group, doubled in the mind palace group, and went up only by 50% in the untrained group. The students trained in the Aboriginal technique were also significantly more likely to list the butterfly names in order than the other two groups. The test didn't require ordering the list, Reser said, but it makes sense that students who were attaching the information to a narrative would remember the information in a certain sequence.

"You can envision, certainly, in the medical field things where order is important," Reser said. "If you're remembering, say, a biochemical pathway or a surgical technique."

The advantage of the Aboriginal technique may have been due to the additional layer of the narrative, Reser said. Or it could have had something to do with the fact that participants physically went to the garden to learn (the mind palace participants simply imagined their childhood homes). The storytelling of the Aboriginal technique was also communal instead of individual, which could have also helped boost memory.

Not enough students returned for a follow-up for the researchers to test the long-term impacts of the different training methods. Study co-author Magaret Simmons, a senior lecturer at the medical school, did gather feedback from the students after the study and found that they enjoyed learning the techniques and that some still used them in their studies.

That was promising, Reser said, as many medical students feel anxious about the amount of memorization they're expected to do. He and his colleagues would like to incorporate these methods into the curriculum, he said, but it's important that they find an Aboriginal instructor who can accurately and sensitively convey the technique. In Aboriginal practice, the method is quite complex, Reser said, with multiple layers of information conveyed through song, stories and art. It also takes hard work and practice to keep the information attached to the narratives fresh.

"We want students to have exposure to Aboriginal culture and to be aware of just how rich and how deep into history this goes," he said.

The findings were published May 18 in the journal PLOS One.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.