Canada's last intact ice shelf just collapsed

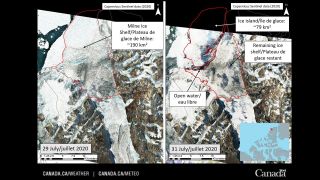

The area of the Milne Ice Shelf is now reduced by 43%.

Milne Ice Shelf was Canada's last intact ice shelf — and it just collapsed.

On July 30 and July 31, the northern part of the Arctic ice shelf began to break off. A mass of ice measuring about 31 square miles (81 square kilometers) — bigger than Manhattan — then detached from the ice shelf and began drifting north, representatives of the Water and Ice Research Laboratory (WIRL) at Carleton University in Ontario, Canada, said in a statement.

By Aug. 3, the escaping ice island had split: one piece measured about 21 square miles (55 square km), while another measured about 9 square miles (24 square km), and both were about 230 to 260 feet (70 to 80 meters) thick, according to WIRL.

And other preexisting fractures in the remains of the ice shelf hint that there may be more ice loss to come, WIRL representatives said.

Related: Images of melt: Earth's vanishing ice

Located on the northwestern coast of Ellesmere Island in Nunavut, the Milne Ice Shelf is about 4,000 years old. Signs of the impending breakup were spotted by Adrienne White, an ice analyst at the Canadian Ice Service, Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), according to WIRL. On Aug. 2, the Canadian Ice Service shared satellite images in a Tweet, reporting that "above normal air temperatures, offshore winds and open water in front of the ice shelf are all part of the recipe for ice shelf breakup."

The shelf's sudden collapse was a close call for scientists studying ice loss in that precarious location, said Arctic ice researcher Derek Mueller, an associate professor in Carleton University's Department of Geography and Environmental Studies.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Our camp area and instruments were all destroyed in this event," Mueller said in a WIRL blog post. "It is lucky that we were not on the ice shelf when this happened."

Ellesmere Island has been losing ice for more than a century. About 100 years ago, a vast, single ice shelf extended along the island's northern coast, spanning more than 3,300 square miles (8,600 square km). By 2000, the shelf was reduced to around 405 square miles (1,050 square km) divided among six large ice shelves — including Milne Ice Shelf — as well as a few smaller ones, Carleton University representatives said.

Since 2003, there have been five major calving events on the Ellesmere Island coast, and there's no question that climate change is driving the drastic ice loss, according to Luke Copland, University Research Chair in Glaciology in the Department of Geography at the University of Ottawa.

And with the region warming at approximately two to three times the global rate — not to mention several summers of record-breaking warmth — "the Milne and other ice shelves in Canada are simply not viable any longer and will disappear in the coming decades," Copland said in the university statement. Indeed, on July 30, NASA imagery revealed that two of Ellesmere Island's giant ice caps had vanished. They had dominated the landscape for hundreds of years, but were erased by climate change in just 40 years, Live Science previously reported.

For now, the enormous ice islands are drifting close to the coastline, their movement restricted by other large chunks of floating ice; the Canadian Ice Service will continue to track them to determine if they could threaten nearby ships or oil rigs, according to the statement.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.