Scientists figure out how new coronavirus breaks into human cells

It could aid in drug development.

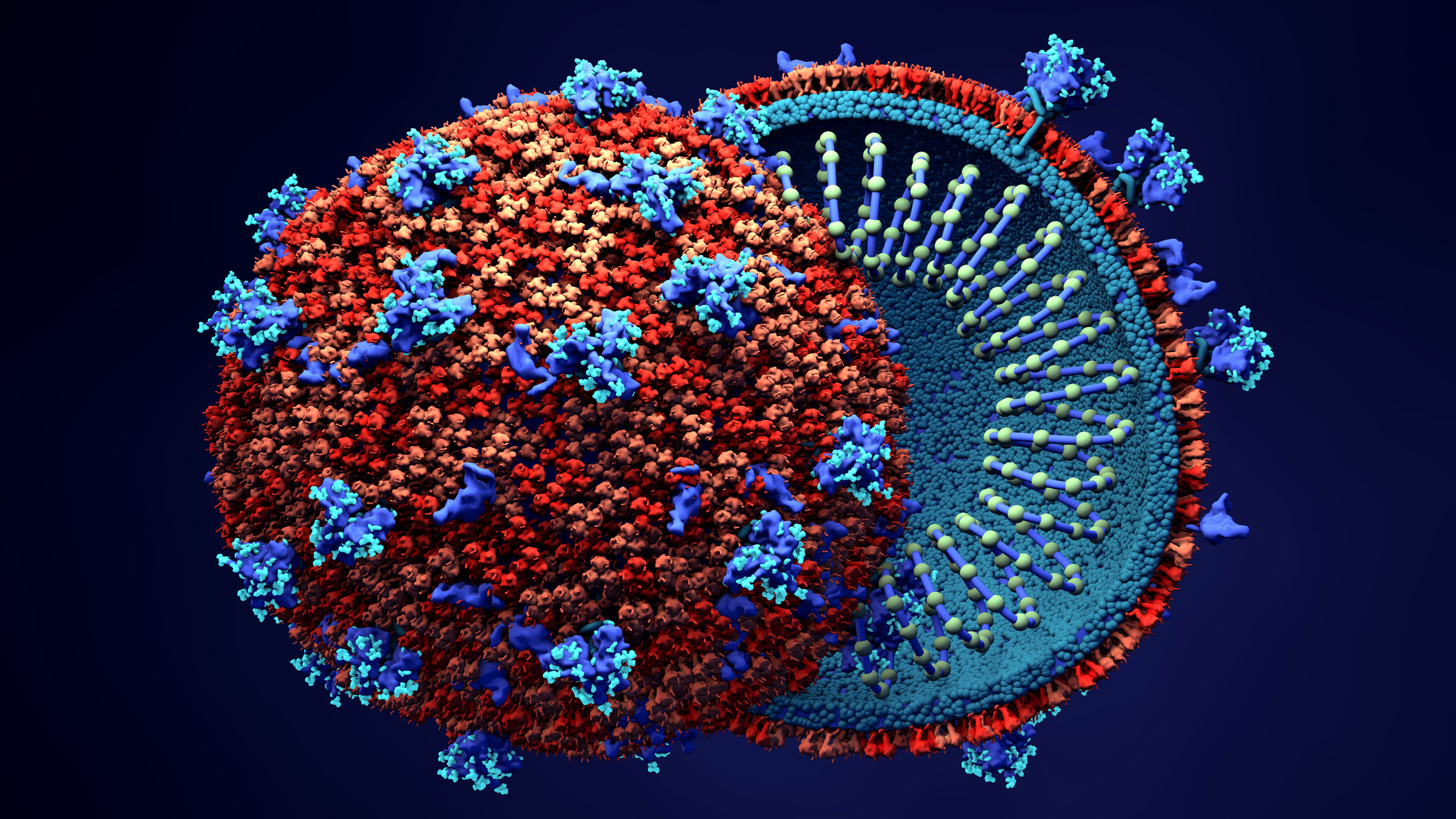

Scientists have revealed the first picture of how the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 binds with human respiratory cells in order to hijack them to produce more viruses.

Researchers led by Qiang Zhou, a research fellow at Westlake University in Hangzhou, China, have revealed how the new virus attaches to a receptor on respiratory cells called angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, or ACE2.

"They have pictures all the way down at the level of the atoms that interact at the binding interface," Thomas Gallagher, a virologist at Loyola University Chicago who was not involved in the new research but studies coronavirus structure, told Live Science. That level of information is unusual at this stage of a new virus outbreak, he said.

"The virus outbreak only began to occur a couple months ago, and within that short period of time, these authors have come up with information that I think traditionally takes much longer," Gallagher said.

That's important, he said, because understanding how the virus enters cells can contribute to research on drugs or even a vaccine for the virus.

A viral entryway

To infect a human host, viruses must be able to gain entry into individual human cells. They use these cells' machinery to produce copies of themselves, which then spill out and spread to new cells.

On Feb. 19 in the journal Science, a research team led by scientists at the University of Texas at Austin described the tiny molecular key on SARS-CoV-2 that gives the virus entry into the cell. This key is called a spike protein, or S-protein. Last week, Zhou and his team described the rest of the puzzle: the structure of the ACE2 receptor protein (which is on the surfaces of respiratory cells) and how it and the spike protein interact. The researchers published their findings in the journal Science on March 4.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"If we think of the human body as a house and 2019-nCoV [another name for SARS-CoV-2] as a robber, then ACE2 would be the doorknob of the house's door. Once the S-protein grabs it, the virus can enter the house," Liang Tao, a researcher at Westlake University who was not involved in the new study, said in a statement.

Zhou and his team used a tool called cryo electron microscopy, which employs deeply frozen samples and electron beams to image the tiniest structures of biological molecules. The researchers found that the molecular bond between SARS-CoV-2's spike protein and ACE2 looks fairly similar to the binding pattern of the coronavirus that caused the outbreak of SARS in 2003. There are some differences, however, in the precise amino acids used to bind SARS-CoV-2 to that ACE2 receptor compared with the virus that causes SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), the researchers said.

"While some might consider the differences subtle," Gallagher said, "they might be meaningful with respect to the strength with which each of those viruses stick."

That "stickiness" could affect how easily a virus transmits from one person to another. If any given viral particle is more likely to enter a cell once it enters the human body, transmission of disease is more likely.

There are other coronaviruses that circulate regularly, causing upper respiratory infections that most people think of as the common cold. Those coronaviruses don't interact with the ACE2 receptor, Gallagher said, but rather, they get into the body using other receptors on human cells.

Coronavirus structure implications

The structure of SARS-CoV-2's "key" and the body's "lock" could theoretically provide a target for antiviral drugs that would stop the new coronavirus from getting into new cells. Most antiviral drugs already on the market focus on halting viral replication within the cell, so a drug that targeted viral entry would be new territory, Gallagher said.

"There is no effective clinical drug that will block that interaction that I know of" that's already in use, he said.

The viral spike protein is also a promising target for vaccines, because it's the part of the virus that interacts with its environment and so could be easily recognized by the immune system, Gallagher said.

Even so, developing either drugs or a vaccine will be a challenging task. Treatments and vaccines not only have to prove effective against the virus, but must also be safe for people, Gallagher said. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention officials have said that the earliest a coronavirus vaccine could be available is in a year to a year and a half.

- The 9 deadliest viruses on Earth

- 28 devastating infectious diseases

- 11 surprising facts about the respiratory system

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save at least 53% with our latest magazine deal!

With impressive cutaway illustrations that show how things function, and mindblowing photography of the world’s most inspiring spectacles, How It Works represents the pinnacle of engaging, factual fun for a mainstream audience keen to keep up with the latest tech and the most impressive phenomena on the planet and beyond. Written and presented in a style that makes even the most complex subjects interesting and easy to understand, How It Works is enjoyed by readers of all ages.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.