Gigantic 'shark-toothed' dinosaur discovered in Uzbekistan

It was nearly 30 feet long.

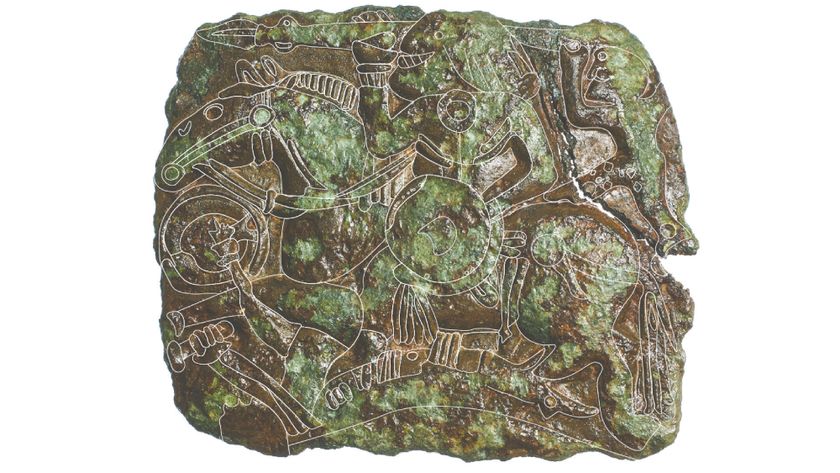

About 90 million years ago, a gigantic apex predator — a meat-eating dinosaur with serrated shark-like teeth — prowled what is now Uzbekistan, according to a new study of the behemoth's jawbone.

The 26-foot-long (8 meters) beast weighed 2,200 pounds (1,000 kilograms), making it longer than an African elephant and heavier than a bison. Researchers named it Ulughbegsaurus uzbekistanensis, after Ulugh Beg, a 15th-century astronomer, mathematician and sultan from what is now Uzbekistan.

What caught scientists by surprise was that the dinosaur was much larger — twice the length and more than five times heavier — than its ecosystem's previously known apex predator: a tyrannosaur, the researchers found.

Related: The 10 coolest dinosaur findings of 2020

The chunk of jawbone was found in Uzbekistan's Kyzylkum Desert in the 1980s, and researchers rediscovered it in 2019 in an Uzbekistan museum collection.

The partial jawbone of U. uzbekistanensis is enough to suggest that the animal was a carcharodontosaur, or a "shark-toothed" dinosaur. These carnivores were cousins and competitors of tyrannosaurs, whose most famous species is Tyrannosaurus rex.

The two dinosaur groups were fairly similar, but carcharodontosaurs were generally more slender and lightly-built than the heavyset tyrannosaurs, said study co-researcher Darla Zelenitsky, an associate professor of paleobiology at the University of Calgary. Even so, carcharodontosaurs were usually larger than tyrannosaur dinosaurs, reaching weights greater than 13,200 pounds (6,000 kg). Then, around 90 million to 80 million years ago, the carcharodontosaurs disappeared and the tyrannosaurs grew in size, taking over as apex predators in Asia and North America.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new finding is the first carcharodontosaur dinosaur discovered in Central Asia, the researchers noted. Paleontologists already knew that the tyrannosaur Timurlengia lived at the same time and place, but at 13 feet (4 m) in length and about 375 pounds (170 kg) in weight, Timurlengia was several times smaller than U. uzbekistanensis, suggesting that U. uzbekistanensis was the apex predator in that ecosystem, gobbling up horned dinosaurs, long-necked sauropods and ostrich-like dinosaurs in the neighborhood, the team said.

"Our discovery indicates carcharodontosaurs were still dominant predators in Asia 90 million years ago," study lead researcher Kohei Tanaka, an assistant professor at the Graduate School of Life and Environmental Sciences at the University of Tsukuba in Japan, told Live Science in an email.

Peter Makovicky, a professor of paleontology at the University of Minnesota who was not involved in the study, agreed that U. uzbekistanensis was likely at the top of the local food chain. "I think this bone is so big that this would have been a very large predatory dinosaur and very likely the apex predator in its ecosystem," Makovicky told Live Science.

The U. uzbekistanensis finding is the last known occurrence of a carcharodontosaur and a tyrannosaur living together before the carcharodontosaurs went extinct, the team said. The team found that U. uzbekistanensis has unique bony bumps above its teeth. However, it also has bony ridges on the sides of its jaw that were similar to the 79.5 million-year-old tyrannosaur Thanatotheristes degrootorum (whose name means "reaper of death") from what is now Canada. It's unclear why both species have these ridges, but perhaps it's a case of convergent evolution, when species that aren't closely related evolve to have similar characteristics, Zelenitsky said.

The study was published online Wednesday (Sept. 8) in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.