What is the amygdala?

Reference Article: Facts about the amygdala.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

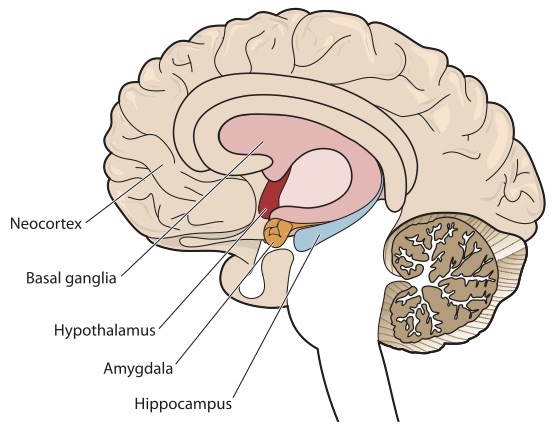

The amygdala is often referred to as the fear center of the brain, but this description hardly does justice to the amygdala's complexity. Located deep in the brain's left and right temporal lobes, our two amygdalae are important for numerous aspects of thought, emotion and behavior, and are implicated in a variety of neurological and psychiatric conditions.

The brain’s two almond-shaped amygdalae are typically no bigger than a couple cubic centimeters in adults and are found near the center of the brain. Although the two halves of the amygdala work together, there also appear to be some aspects of amygdala function that predominate on each side.

(Video courtesy of Beyeler et al. 2018.)

The amygdala and emotions

It's true that the amygdala is involved in fear, particularly fear conditioning — the process by which we and many other animals learn to associate a negative stimulus, such as an electric shock, with another factor according to an article in the journal Molecular Psychiatry. Additionally, amygdala activity is deeply connected to the emotional response to pain.

But the amygdala is also involved in the experience of other emotions — including positive emotions such as those triggered by reward, according to Anna Beyeler, a neuroscientist at the Neurocentre Magendie in Bordeaux, France. Beyeler studies this process at a microscopic level and has shown that different types of stimuli cause varying responses in different neurons of the amygdala in mice. For example, she's found that when the mice are given something sweet, their amygdala sends signals to the part of the brain that's involved in reward.

The amygdala also plays a role in behavior, with aggression being one notable example. In extreme circumstances, a procedure in which part or all of the amygdala is removed or destroyed (called an amygdalotomy) is performed (with consent) on people with severe, frequent and uncontrollable outbursts of aggression that put themselves or others at risk, as described in a 2008 review published in the Journal of Neurosurgery. Following the procedure, many patients experience a reduction in, or even resolution of, the aggressive behaviors. But other patients relapse or do not benefit at all, which suggests that the amygdala is not the only mediator of aggression. Amygdalotomy has also been associated with impairment in the ability to remember faces and interpret facial expressions despite not causing a reduction in overall intelligence.

These results and other research on people with damage to or complete destruction of the amygdala further highlight the many functions of this brain region.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Urbach–Wiethe disease is an exceptionally rare genetic condition in which the amygdala is often severely damaged. One patient with the disease experienced complete destruction of the left and right amygdala. The patient, called S.M., or SM-046, exhibited almost no fear, consistent with the stereotypical role attributed to the amygdala, but also exhibited little natural sense of personal space, according to a study in the journal Nature. Compared to people with functioning amygdalae, the subject also had difficulty remembering facts presented in emotional stories, according to research published in the journal Learning & Memory.

The amygdala and psychiatric disorders

More subtle disruptions in typical amygdala function are associated with a variety of psychiatric disorders. Dysfunction of the amygdala has been observed in patients with anxiety disorders, such as social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder and phobias.

"Many studies using human brain imaging have shown that the amygdala is overactivated in patients with these anxiety disorders, as well as in patients suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder," Beyeler said. In many other psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder and substance use disorders (particularly alcohol use disorder), dysfunction of the amygdala also appears to be involved, although the relationships between the amygdala and these disorders has not been as well studied.

There may also be differences in the way the amygdala functions in people with autism relative to neurotypical people. Individuals with autism may have more active amygdalae on average, and their amygdalae may not dull their response after repeated exposure to the same stimulus, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Psychiatry.

Related: 10 things we learned about the brain in 2019

In neurotypical individuals, exposure to an image of a face triggers amygdala activity, but repeated exposure to images of the same face causes amygdala activity to settle down. In people with autism, this effect may be dampened, such that amygdala activity spikes every time the face is shown. Some researchers speculate that high amygdala activity may be one reason that people with autism often don't keep their gaze fixed on other people's faces during a conversation, but such a connection is difficult to prove.

Like many brain regions, the amygdala shows signs of lateralization — that is, the amygdala in one hemisphere is different from the one in the other hemisphere. Often, amygdala activity in response to certain cues appears to be increased on the left more than the right or vice versa, but the two amygdalae are still working together. Also, as Beyeler's work has demonstrated, the amygdala's internal activity is complex, with neurons in different regions of the amygdala connecting to different parts of the brain.

Given the amygdala's multitude of functions, the oversimplification of simply calling it the brain's fear center is understandable. With further study, experts are likely to discover even more processes in which this small region of the brain is involved.

Additional resources:

- This video interview with neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux gives a five-minute rundown of all things amygdala.

- This free book chapter has a more in-depth look at the amygdala.

- Learn more about the anatomy of the brain in this video clip from BrainFacts.org.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus