Dino-era bird had the head of a Velociraptor and beak of a toucan

Meet the "Toucan Sam" of the dinosaur era.

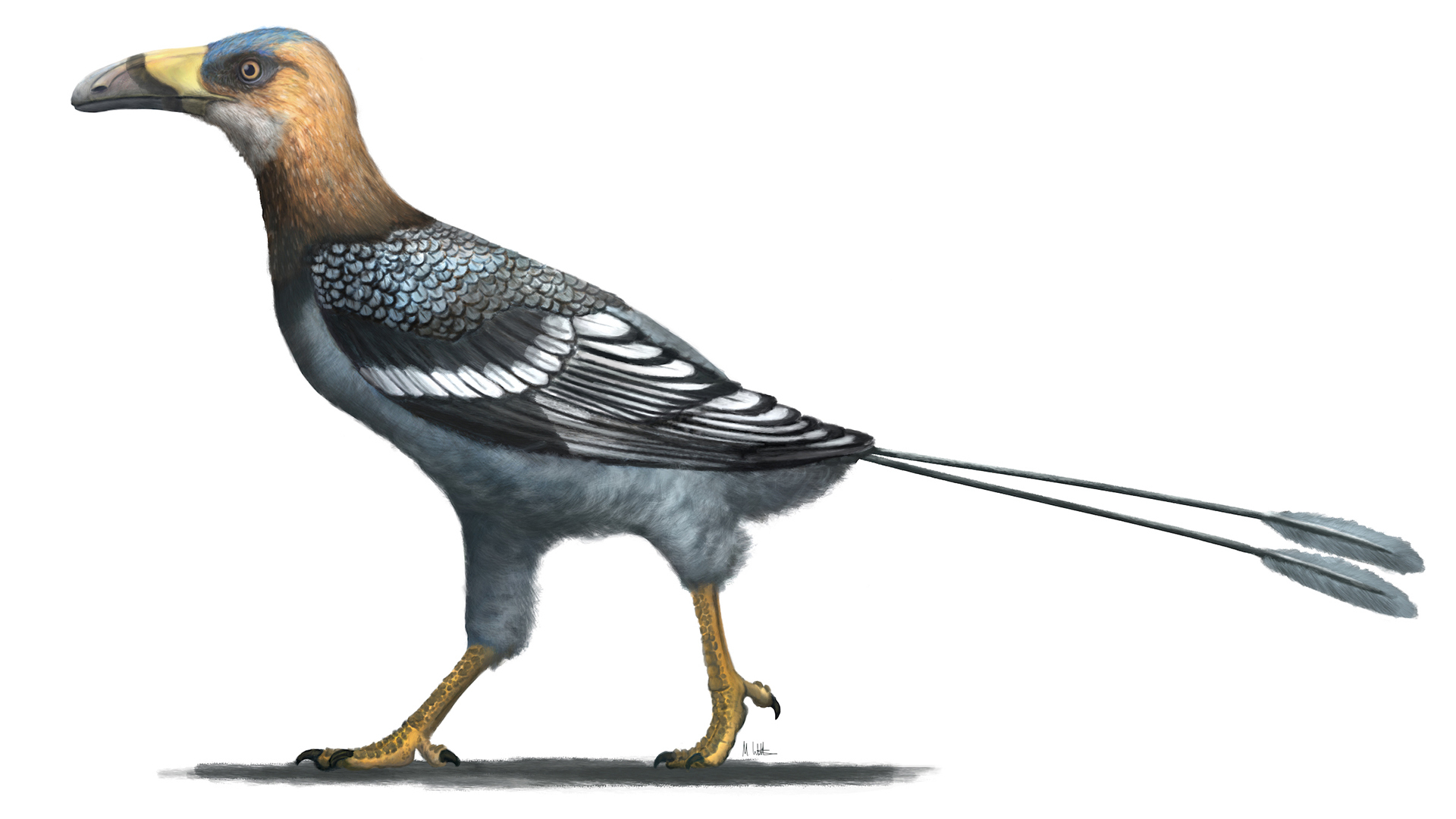

In what may be one of the weirdest animal mash-ups, scientists have found the 68 million-year-old fossilized skull of an early bird with a Velociraptor-like face and a toucan-like beak, a new study finds.

This crow-size bird lived in northwestern Madagascar during the late Cretaceous, when dinosaurs walked the Earth. And its bizarre beaky face made it one of a kind.

"Birds from the Mesozoic [the dinosaur era], or any time for that matter, do not have faces built like this," study co-researcher Patrick O'Connor, professor of anatomy at Ohio University, told Live Science in an email.

Related: Photos: Velociraptor cousin had short arms and feathery plumage

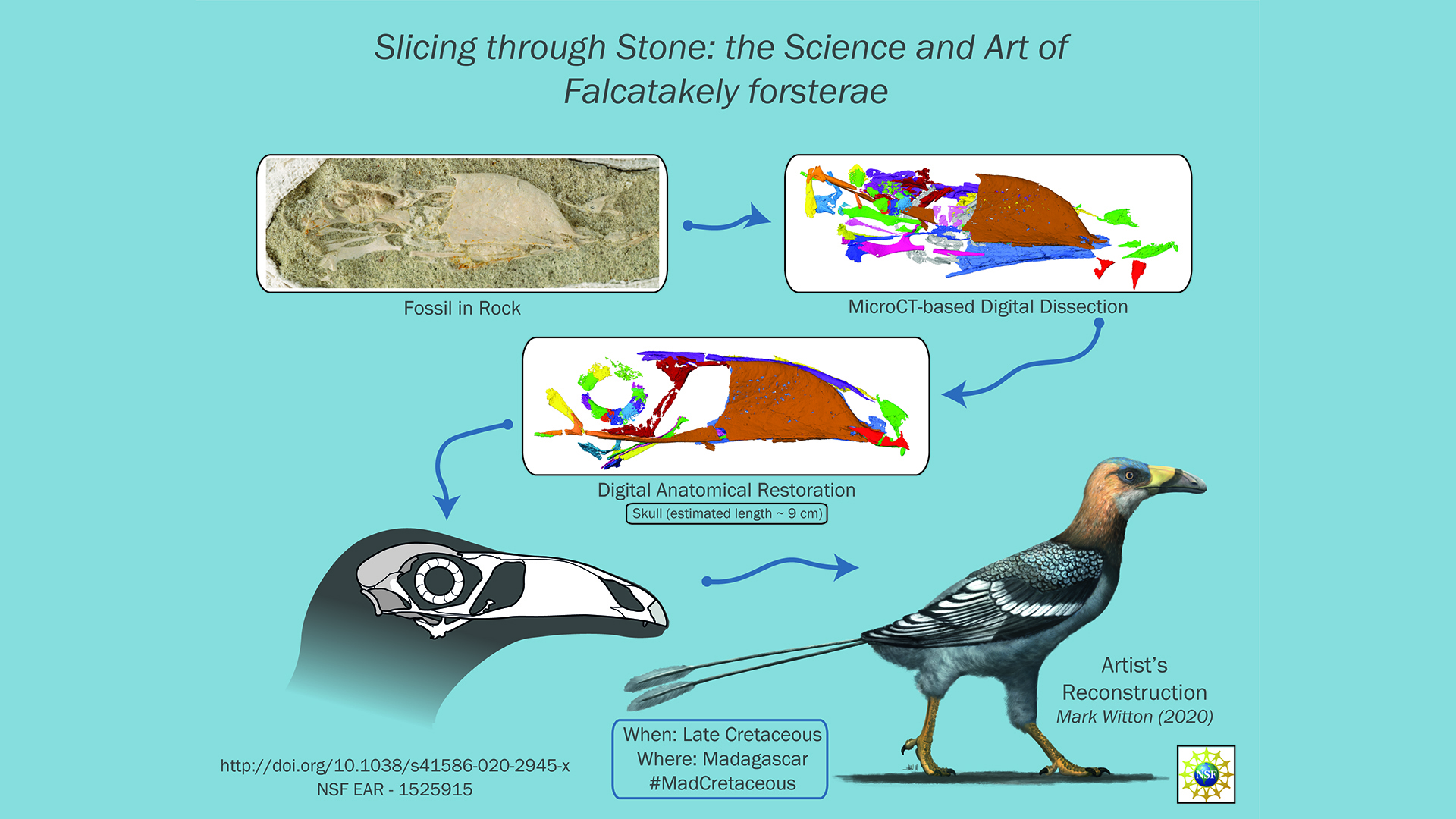

Researchers found the bird's partial but "exquisitely preserved" skull in 2010 in a block of muddy sandstone. They didn't CT scan it until 2017, O'Connor said. In that moment, they realized this 3-inch-long (8.5 centimeters) skull — so small it could fit in the palm of your hand — had "a beak never before seen in the Mesozoic," study co-researcher Alan Turner, associate professor of anatomy at Stony Brook University in New York, told Live Science in an email.

Here's why: In modern birds, the skeleton underneath the beak is largely formed by a single bone. "You can sort of think of this as a set of rules that all living birds follow," from skinny beaked hummingbirds to fat-beaked shoebills, Turner said.

But in this newfound bird — dubbed Falcatakely forsterae, a combination of Latin and Malagasy words describing the fearsome beast's small size and scythe-like beak — this beak-building "rule" wasn't yet established. Instead, most Mesozoic birds, including Archaeopteryx, had snouts more like their dinosaur ancestors, with both a bone underneath the beak and a large upper jawbone.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Falcatakely made up its face with the same bones and in a similar way as an animal like Velociraptor did," Turner said. "What is remarkable is that with this ancestral arrangement of bones, Falcatakely evolved a beak shape strongly reminiscent of modern birds with high, long upper bills."

Put another way, this toucan-like beak is an example of convergent evolution, when a similar feature evolves independently in separate groups. But Falcatakely evolved its long upper bill tens of millions of years before modern birds such as toucans and hornbills did, Turner said. "So, it is actually the toucans and the hornbills that have the convergent morphology. Falcatakely beat them to it," he said.

The study was published online Wednesday (Nov. 25) in the journal Nature.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.