'Garbage dump' discovered in ancient Egyptian tomb dedicated to fertility goddess

The dump is 3,500 years old.

An ancient Egyptian "garbage dump" discovered within a temple honoring the powerful female Pharaoh Hatshepsut is piled high with offerings to a fertility goddess, archaeologists report.

Archaeologists unexpectedly found the rubbish heap in a tomb within the 3,500-year-old Hathor cult complex, a three-temple complex that sits within the Hatshepsut Temple at Deir el-Bahari (also spelled Deir el-Bahri), near Luxor. Even though the dump was hidden in an early Middle Kingdom tomb, many of the artifacts in the dump date to the New Kingdom, which includes the 18th, 19th and 20th dynasties that ruled from the 16th century B.C. to the 11th century B.C.

Many of these artifacts are votive offerings — special objects, like figurines, purposefully left for deities, religious leaders or establishments — that people in ancient Egypt gave to Hathor, the goddess of fertility.

"The deposit of votive offerings to Hathor discovered in this tomb indicates that this part of Hatshepsut's temple was not used for worship and was treated as a place to dump rubbish," said Patryk Chudzik, the director of the Polish-Egyptian Archaeological and Conservation Expedition to the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari, and an archaeologist with the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology at the University of Warsaw (PCMA UW).

Related: Photos: Newfound Egyptian tomb has colorful murals of man and wife

The female ruler Hatshepsut often invoked Hathor, so it's no surprise she had a chapel dedicated to the goddess at the temple, according to the World History Encyclopedia.

Chudzik's team discovered the Middle Kingdom tomb with the rubbish heap in spring of 2021, while investigating the Hathor cult complex, and working to conserve and reconstruct it, especially for its public opening to the Hathor Shrine.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"When we found it, the tomb was filled with rock debris," as well as a vast number of artifacts from the early Middle Kingdom, votive offerings to Hathor from the New Kingdom and the remains of a late 20th-dynasty burial, Chudzik told Live Science in an email. "The oldest materials from the votive offerings to Hathor are dated to the 18th dynasty, while the others were made during the reign of the 19th and 20th-dynasty pharaohs," he said.

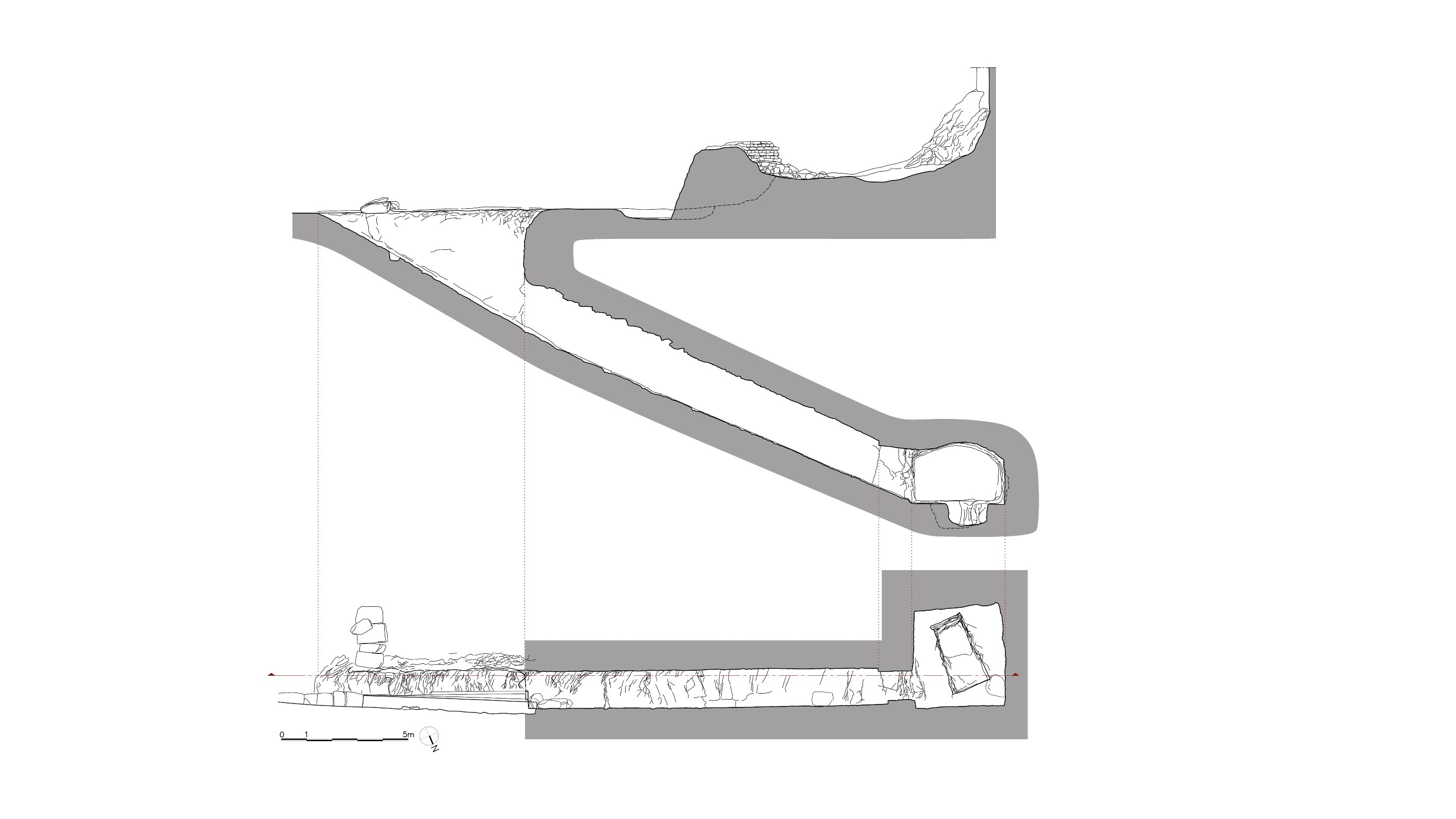

The garbage dump is huge, he noted. The debris fills the tomb's roughly 50-foot-long (15 meters) corridor, with its highest point at 1.6 feet (0.5 m). Despite the dump's size, other archaeologists have missed its importance. Swiss archaeologist Édouard Naville originally discovered the tomb in the late 1800s, but beyond noting the excessive rubble, he didn't investigate the garbage dump, according to Science in Poland, a Polish news website jointly run by independent media and the government. An American expedition excavating the temple in the 1920s also skipped over the deposit.

The new investigation found the votive offerings to Hathor include glazed ceramic, known as faience, and clay vessels; clay cow figurines; fragments of limestone and granite statues; small faience female figurines that are representations of Hathor; and various types of amulets.

"These items originally were left by the ancient Egyptians in the Hathor Shrine above the tomb [we excavated]," Chudzik said. "We suggest that sometimes there were so many offerings that there was no empty space for new objects, and that is why the priests from the Hatshepsut temple collected them from time to time and took them outside the temple area, making rubbish deposits."

The discovery also shows that "the tomb was open and could be entered at the time of Hatshepsut and during the reign of successive kings of Egypt," Chudzik said. Other archaeologists had suggested that there was a ramp leading to the shrine of Hathor, but the new finding shows that this wasn't the case.

The fact that there likely wasn't a ramp "is an important result that makes it possible to reconstruct the history of the construction not only of the shrine of Hathor, but also of the entire temple of Hatshepsut," he said. However, research into the temple is ongoing. "These are only preliminary conclusions," Chudzik said. "For more we must wait until a comprehensive study of the material has been completed."

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.