3 Egyptian mummy faces revealed in stunning reconstruction

A forensic artist created the 3D reconstructions based on genetic data.

The faces of three men who lived in ancient Egypt more than 2,000 years ago have been brought back to life. Digital reconstructions depict the men at age 25, based on DNA data extracted from their mummified remains.

The mummies came from Abusir el-Meleq, an ancient Egyptian city on a floodplain to the south of Cairo, and they were buried between 1380 B.C. and A.D. 425. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Tübingen, Germany, sequenced the mummies' DNA in 2017; it was the first successful reconstruction of an ancient Egyptian mummy's genome, Live Science reported at the time.

And now, researchers at Parabon NanoLabs, a DNA technology company in Reston, Virginia, have used that genetic data to create 3D models of the mummies' faces through a process called forensic DNA phenotyping, which uses genetic analysis to predict the shape of facial features and other aspects of a person's physical appearance.

Related: Image gallery: The faces of Egyptian mummies revealed

"This is the first time comprehensive DNA phenotyping has been performed on human DNA of this age," Parabon representatives said in a statement. Parabon revealed the mummies' faces on Sept. 15 at the 32nd International Symposium on Human Identification in Orlando, Florida.

Scientists used a phenotyping method called Snapshot to predict the men's ancestry, skin color and facial features. They found that the men had light brown skin with dark eyes and hair; overall, their genetic makeup was closer to that of modern individuals in the Mediterranean or the Middle East than it was to modern Egyptians', according to the statement.

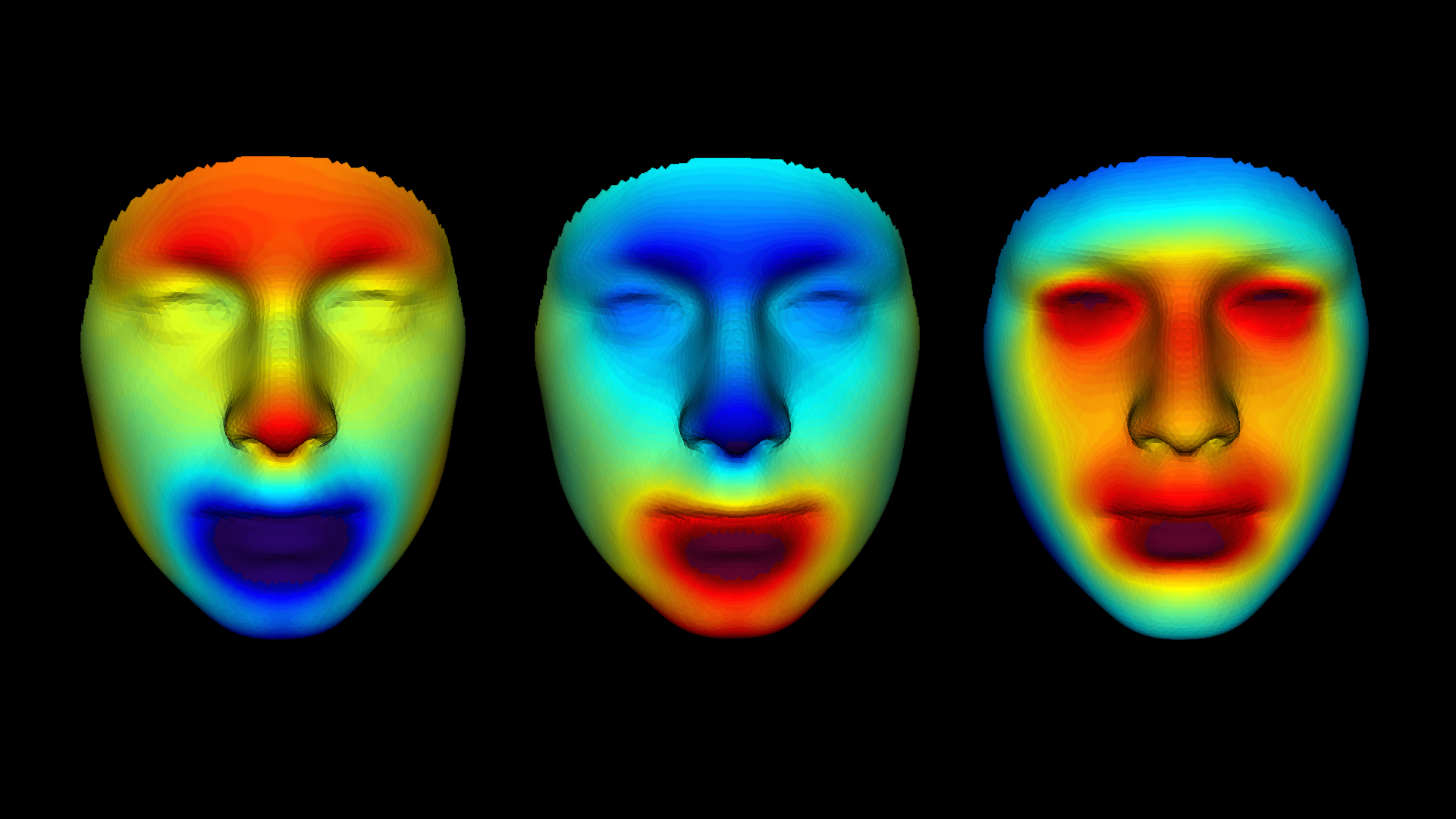

The researchers then generated 3D meshes outlining the mummies' facial features, and calculated heat maps to highlight the differences between the three individuals and refine the details of each face. Parabon's forensic artist then combined these results with Snapshot's predictions about skin, eye and hair color.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Working with ancient human DNA can be challenging for two reasons: the DNA is often highly degraded, and it's usually mixed with bacterial DNA, said Ellen Greytak, Parabon's director of bioinformatics.

"Between those two factors, the amount of human DNA available to sequence can be very small," Greytak told Live Science in an email. However, because the vast majority of DNA is shared between all humans, scientists don't need the entire genome to glean a physical picture of a person. Rather, they only need to analyze certain specific spots in the genome that differ between people, known as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Many of these SNPs code for physical differences between individuals, Greytak said.

However, sometimes ancient DNA doesn't provide enough SNPs to pinpoint a given trait. In those cases, scientists can infer absent genetic data from values of other SNPs nearby, said Janet Cady, a Parabon bioinformatics scientist. Statistics that are calculated from thousands of genomes reveal how closely associated each SNP is with an absent neighbor, Cady told Live Science in an email. From there, the researchers can make a statistical prediction of what the missing SNP was.

The processes used on these ancient mummies could also help scientists to recreate faces to identify modern remains, Greytak told Live Science. Of the approximately 175 cold cases that Parabon researchers have helped to solve using genetic genealogy, so far nine were analyzed using the techniques from this study, Greytak said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.