3,200-year-old Egyptian-built fortress found in Israel

The Egyptians and the Canaanites built this fortress.

Archaeologists in Israel have discovered a 3,200-year-old fortress built by the Egyptians and Canaanites, the ancient foes of the Israelites in the bible. The fortress was built to keep the newly arrived Philistines out of the region.

The military structure, dubbed Galon Fortress, dates to the middle of the 12th century B.C., when the biblical characters of Deborah and Samson are thought to have lived, according to the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA).

The fortress highlights just how much unrest rocked the area at that time, the IAA said. At the time, the inhabitants of the region — known as the land of Canaan — were ruled by the ancient Egyptians.

Related: Biblical battles: 12 ancient wars lifted from the bible

Then, the Israelites and the Philistines arrived during the 12th century B.C., prompting the Canaanites and Egyptians to ultimately build the recently unearthed fortress.

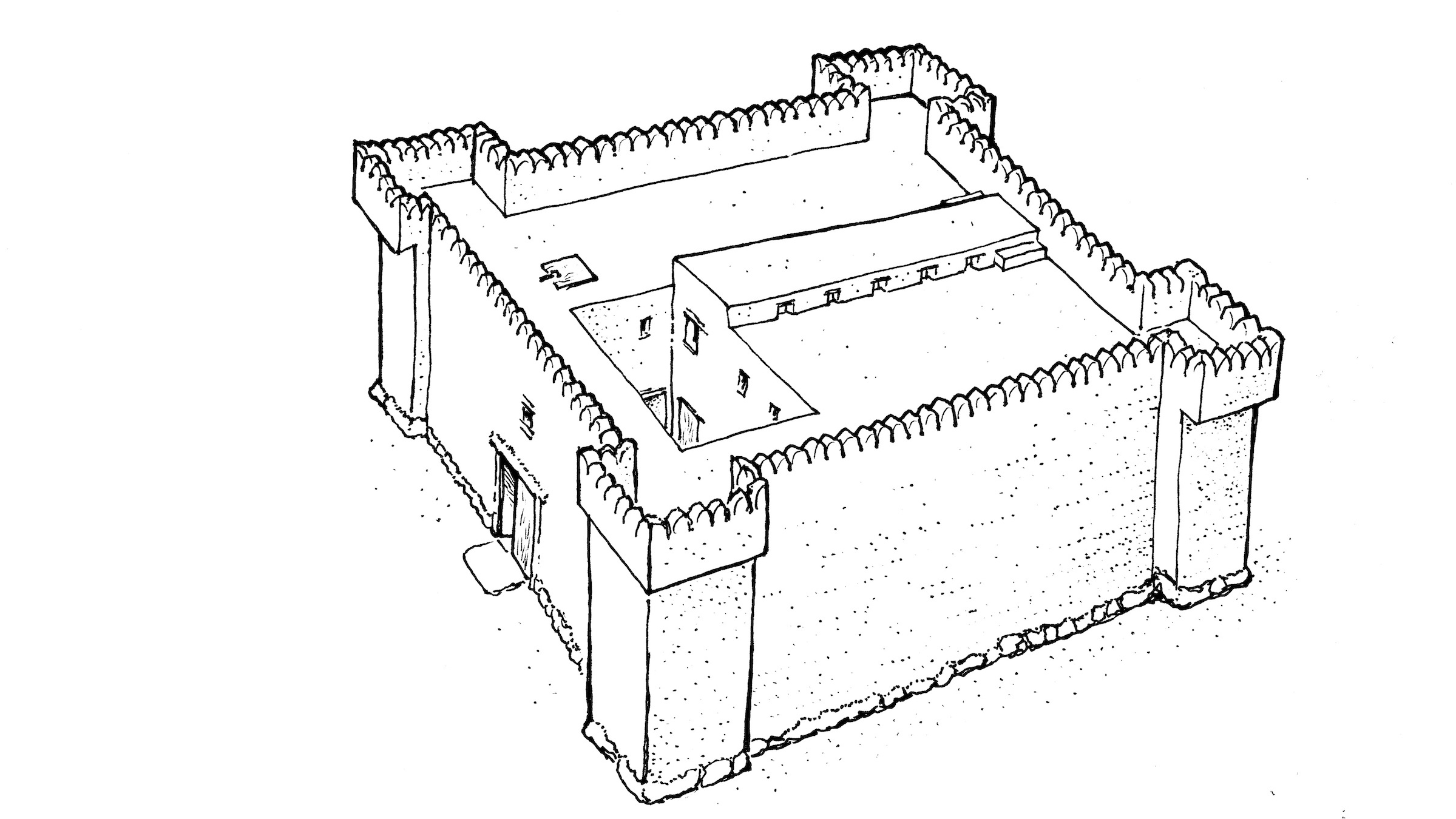

Teenage volunteers with the IAA found the fortress during an excavation close to Kibbutz Galon, a kibbutz (a collective community) about 40 miles (70 kilometers) south of Jerusalem. The remains of the fortress and the ceramic artifacts within are remarkable; the nearly 60-foot-by-60-foot (18 by 18 meters) fortress had watchtowers in each of its four corners, and a threshold at the entrance carved from a massive rock weighing 3.3 tons (3 metric tons).

When people entered the fortress, which employed an Egyptian style of architecture, they would have seen a courtyard paved with slab stones and rising columns at the center. Each side of the fort had rooms, where the archaeologists found hundreds of pottery vessels, some of them whole, including a bowl and cup that were likely used for religious rituals, Saar Ganor and Itamar Weissbein, IAA archaeologists said in a statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

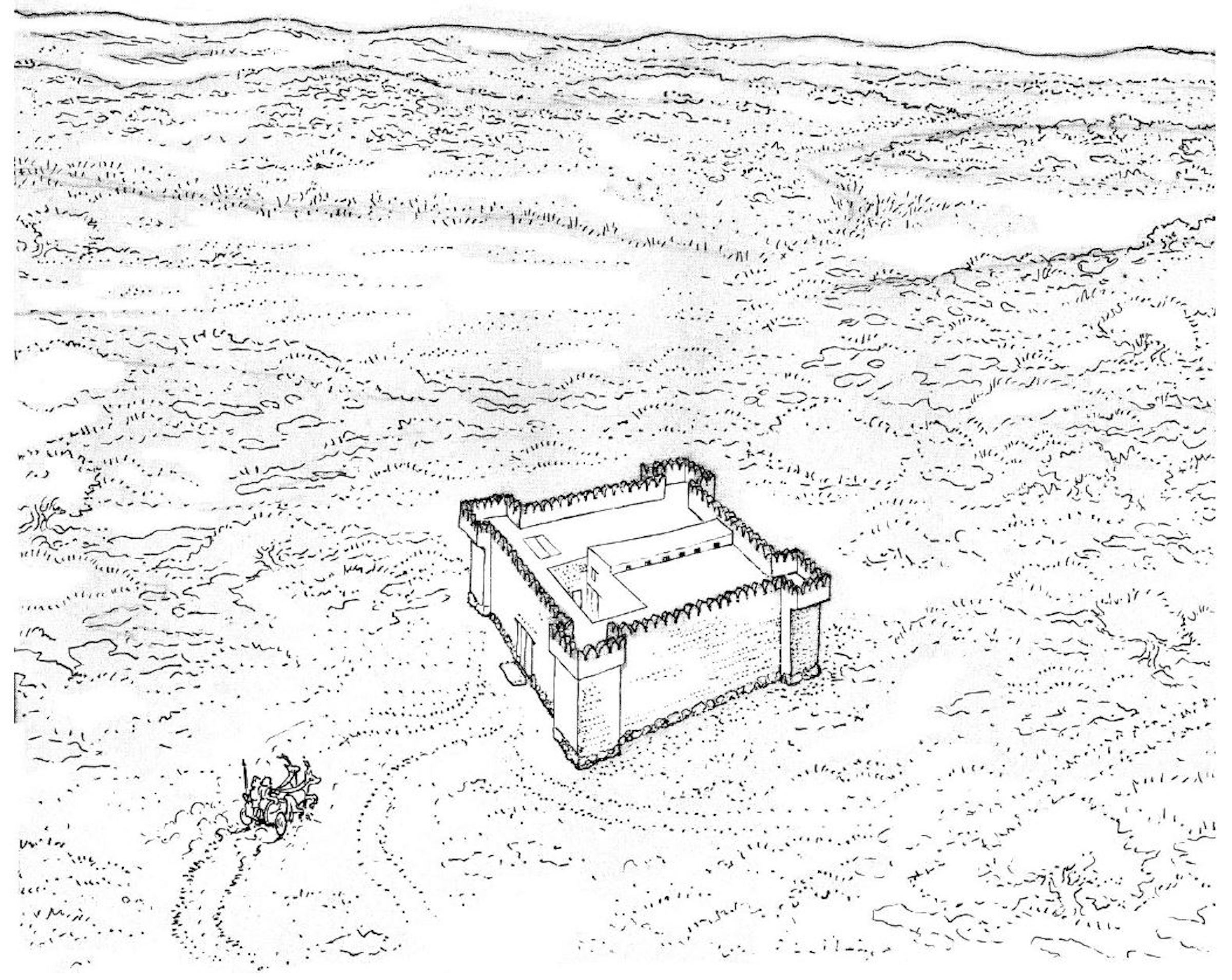

It's unsurprising that the fortress dated to this tumultuous time of "violent territorial disputes," Saar and Weissbein said. The ancient Israelites had established themselves in non-fortified settlements in the Judean Mountains, which run through what is now central Israel and the West Bank. The Philistines accumulated power in the west, along the Mediterranean Sea's southern coast and the plains beyond it, where they built big cities such as Ashkelon, Ashdod and Gat, the archaeologists said. Galon fortress was smack in the middle of the Philistine and Israelite territories.

The Philistines — known for the legendary giant Goliath, who fought King David, according to the Hebrew Bible — likely descended from people in Greece, Sardinia and maybe even Iberia who migrated across the Mediterranean Sea to the Levant (the lands immediately east of the Mediterranean) about 3,000 years ago, according to a 2019 study in the journal Science Advances.

As the Philistines tried to conquer more land in the Levant, they confronted the Egyptians and Canaanites, they said.

"It seems that Galon fortress was built as a Canaanite/Egyptian attempt to cope with the new geopolitical situation," Saar and Weissbein said. The fortress was "built in a strategic location, from which it is possible to watch the main road that went along the Guvrin river — a road connecting the coastal plain to the Judea plains," Saar and Weissbein said.

However, the geopolitical situation changed in the middle of the 12th century B.C., when the Egyptians left the land of Canaan and retreated back to Egypt, leaving the Canaanites alone to defend their turf.

"Their departure led to the destruction of the now unprotected Canaanite cities — a destruction that was probably led by the Philistines," Saar and Weissbein said.

The discovery of Galon fortress "provides a fascinating glimpse into the story of a relatively unknown period in the history of the country," Talila Lifshitz, director of the community and forest department in the southern region of the Jewish National Fund, said in the statement.

The fortress is now open to the public, due to a collaboration between the IAA and the Jewish National Fund.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.