Ancient hippo-size reptile was a quick and ferocious killing machine

The pre-dinosaur reptile Anteosaurus was hefty, swift and deadly.

A hippopotamus-size predator that lived 265 million years ago was unexpectedly speedy for such a bulky beast.

Scientists previously viewed the dinosaur-like reptile Anteosaurus as slow and plodding because of its massive, heavy head and bones. However, a new analysis of the animal's skull proved otherwise, revealing adaptations that would have made Anteosaurus a fast-moving juggernaut.

With this deadly combination of speed and power — along with a mouthful of bone-crushing teeth — Anteosaurus would have been one of the most fearsome apex predators on the African continent during the middle part of the Permian period (299 million to 251 million years ago), according to a new study.

Related: Wipe out: History's most mysterious extinctions

Anteosaurus belonged to a reptile family that predated dinosaurs, known as dinocephalians, and they all died out about 30 million years before the first dinosaurs appeared. Dinocephalians were also part of a larger group of animals called therapsids, which includes the ancestors of mammals.

"Dinocephalians were among the first herbivorous and carnivorous species that dominated terrestrial ecosystems," said lead study author Julien Benoit, a senior researcher at the Evolutionary Studies Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits University) in Johannesburg, South Africa.

What's more, dinocephalians were some of the earliest amniotes — animals that hatch from eggs laid on land or retained inside the mother's body — to evolve very large body size, according to the study. Many dinocephalians also had sturdy skulls with reinforced horns, buffers and bumps, suggesting that the animals may have used their heavy heads as battering rams.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Heavy ... and amphibious?

Because Anteosaurus' skeleton was so massive, researchers previously hypothesized that it was a slow-moving animal that likely ambushed its prey, Benoit told Live Science in an email.

"Some authors even suggested that it might have been amphibious because it was just too heavy to support its weight on land — similar to what used to be imagined about dinosaurs," Benoit said. "Our study suggests it is quite the opposite."

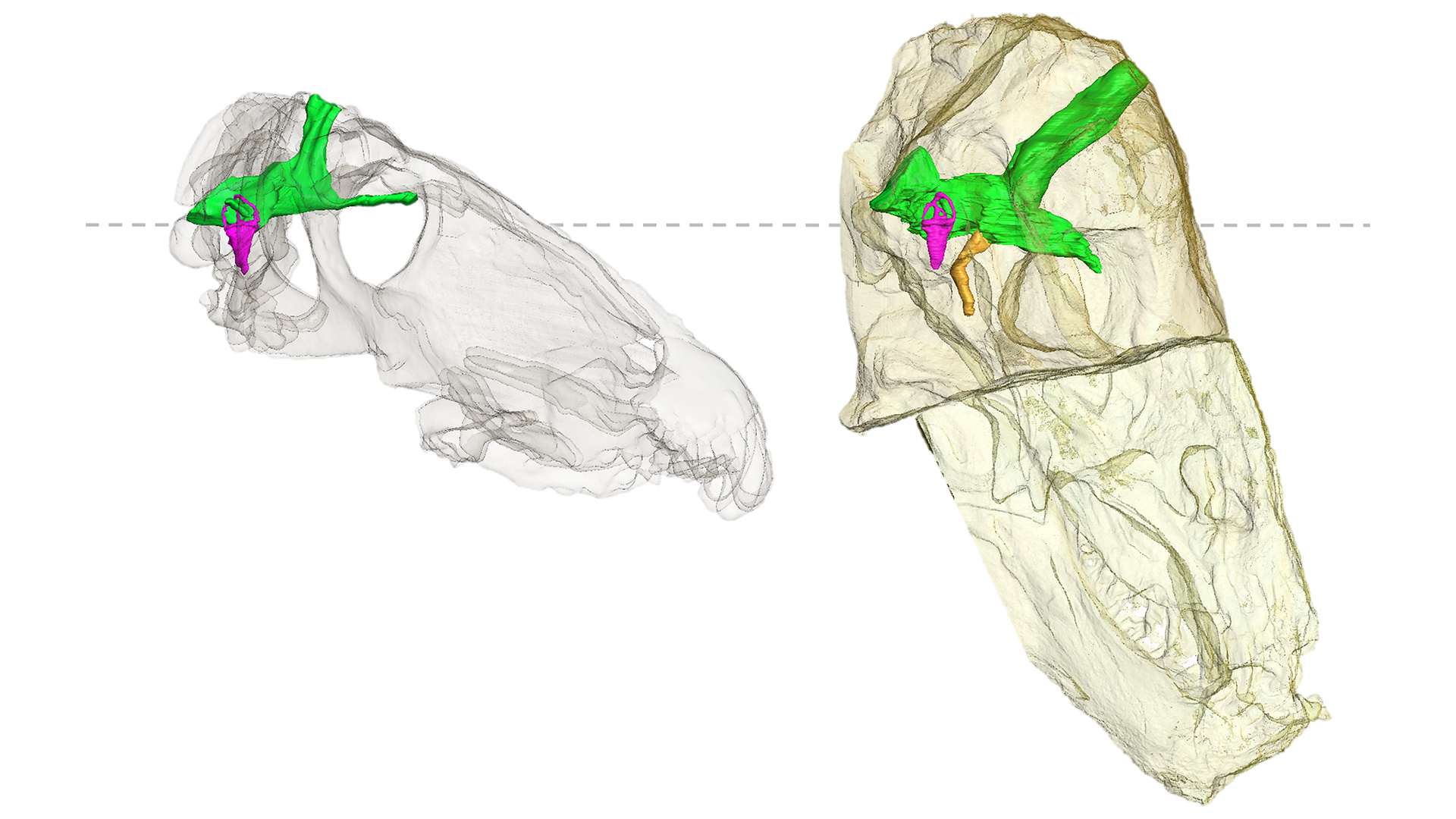

Anteosaurus had a weighty, knobby skull with a prominent crest on the snout, and Benoit and his co-authors questioned if Anteosaurus was a head-butter, like some of its dinocephalian relatives. To find out, they scanned the skull of a juvenile Anteosaurus magnificus from the Karoo desert region in South Africa.

They used X-ray microtomography (micro-CT) to create high-resolution images that revealed the interior of the skull in exceptional detail and then used those images to reconstruct the skull and its long-gone internal structures as digital 3D models.

Their scans provided the first-ever glimpse of an Anteosaurus' inner ear — and it was definitely not the inner ear of a head-butting animal, Benoit said.

"When the skull is adapted to head butting, the inner ear is tilted backward because of a reorientation of the braincase to absorb head-to-head combat stress," Benoit said. But A. magnificus lacked that adaptation, so it probably didn't use its head for ramming.

"Instead, it would have used its massive canines for fighting," Benoit said.

An agile killer

The scientists also found surprising clues about Anteosaurus' abilities by reconstructing and measuring the dimensions of its inner ear canal, which is a feature associated with balance, and lobes in its cerebellum called the flocculi, which assist with agility and help predators lock their eyes on their prey. The shapes of these structures resembled those found in predators such as cats and velociraptors, hinting that Anteosaurus had a nervous system adapted to catching fast-moving prey, Benoit said.

"When you contemplate the bones of this animal, they look so heavy and massive that this really came up as a surprise," he said. "I guess this comes in part from the misconception that fossilized bones are so heavy, it is hard to imagine that they were once light and pulled by muscles powerful enough to make them move."

Superior swiftness and agility would have enabled Anteosaurus to prey on another group of big-skulled and formidable Permian reptiles known as therocephalians, or "beast-heads," placing it at the top of the food chain, according to the study. And this is just the beginning of what researchers are yet to discover about the strange reptiles that came before the dinosaurs, Benoit said.

"Soon we will be capable of comparing the brain and inner ear of Anteosaurus to many of its close relatives," he said. "This will shed new light on the interactions between animals of an entirely extinct ecosystem."

The findings were published online Feb. 18 in the journal Acta Palaeontologica Polonica.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.