Ancient Mars may have been covered in ice sheets

The Red Planet may not have been quite so habitable, after all.

Early Mars may not have been quite the warm, wet paradise scientists have hoped for — not if the valleys scarring its surface work the same way as their counterparts here on Earth do.

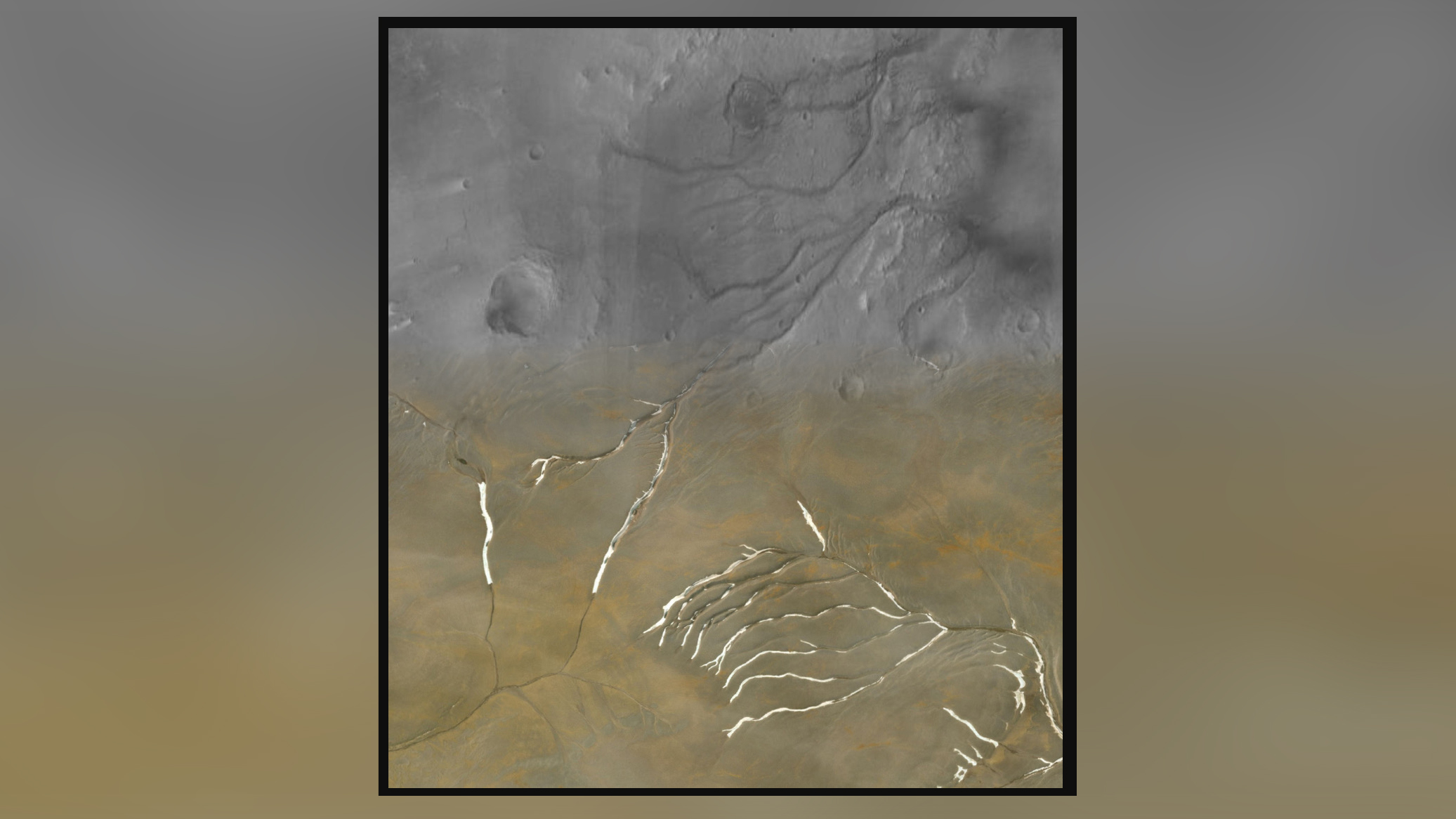

That's the conclusion of new research that tried to suss out what the Red Planet really looked like during its first billion years by analyzing more than 10,000 segments of valleys on Mars. In particular, the scientists were inspired by the look of Devon Island in the Canadian Arctic, which is dry and frigid. According to the new analysis, some Martian valleys may have been formed by a similar process to those lurking below Devon Island's ice.

"If you look at Earth from a satellite, you see a lot of valleys: some of them made by rivers, some made by glaciers, some made by other processes, and each type has a distinctive shape," Anna Grau Galofre, lead author of the new research and a geophysicist at Arizona State University, said in a statement released by the University of British Columbia, where she did the research. "Mars is similar, in that valleys look very different from each other, suggesting that many processes were at play to carve them."

Related: The search for water on Mars in photos

And one of those processes, the researchers say, could be meltwater flowing between an ice sheet and the ground below it. That sort of erosion produces a different valley pattern than one generated by a free-flowing river, according to the scientists, and many of the Martian valleys they studied seem to be a better match for that ice sheet formation model.

Grau Galofre and her colleagues started with detailed maps produced by the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter, which flew on NASA's Mars Global Surveyor spacecraft and studied the Red Planet between 1997 and 2001. The scientists developed a program that incorporated six different characteristics about each of more than 10,000 valley segments, then compared each cluster with attributes based on four different formation scenarios.

According to that analysis, 22 of the 66 networks evaluated best match the patterns formed by meltwater running under a glacier, the researchers concluded. Another nine best match patterns formed by glaciers themselves, whereas 14 best match patterns formed by rivers. Most of the rest weren't distinct enough matches for a specific formation scenario.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers also found that the valleys that looked like they were formed by meltwater running beneath glaciers were spread across Mars, while those that looked to have been formed by rivers were concentrated around Arabia Terra, a particularly old region of Mars, according to NASA.

Rivers and the melted water slipping below a glacier imply one key difference about their surroundings: temperature. The scientists argue that their new research matches well with recent theories that Mars may have been cooler in its distant past than other hypotheses have suggested.

"For the last 40 years, since Mars's valleys were first discovered, the assumption was that rivers once flowed on Mars, eroding and originating all of these valleys," Grau Galofre said. "We tried to put everything together and bring up a hypothesis that hadn't really been considered."

The research is described in an article published Monday (Aug. 3) in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.