Sacred chickens, witches and animal entrails: 7 unusual ancient Roman superstitions

The ancient Roman believed in spells, witches and curses.

To modern people, the ancient Romans seem deeply superstitious. Stories abound of their peculiar beliefs, and some have echoes in the traditions of today. Shakespeare's famous warning by a soothsayer to Julius Caesar of his assassination — "Beware the ides of March" — is still quoted by people today, even if they only vaguely know what the ides were. (The "ides" were the middle day of a month — so that's March 15, the date of Caesar's murder in 44 B.C.)

Caesar's reported warning involves a superstition that seems characteristic of the place and time, but superstition in ancient Rome was more complicated than it might appear. Here are seven unusual ancient Roman superstitions and what they may have meant.

1. Carrying a bride over the threshold

Many Romans considered it bad luck not to observe the tradition of a groom carrying his new bride over the threshold of her new house, according to a folklore compilation at Dartmouth College, and this is still practiced after many wedding ceremonies today. The idea was to prevent the bride from tripping on her first entry, which supposedly would have angered the spirits that protected that particular home, such as the domestic deities called "penates."

Roman tradition attributed the practice to a founding myth of the city often called "The Rape of the Sabine Women"; the word "rape" comes from the Latin word "raptio," meaning "abduction." According to the version of the story told by the Roman historian Livy, Rome was founded in about the eighth century B.C. by mostly male bandits, who then raided the villages of their neighbors, the Sabines, to abduct women to be their wives. And so the tradition of a groom carrying his bride over the threshold was said to represent the bride's reluctance to become a Roman wife and her desire to stay with the family of her father.

Ken Dark, an emeritus professor of archaeology and history at Reading University in the United Kingdom, cautioned that not everyone in ancient Rome may have believed in the displeasure of the penates or other gods, but they practiced such traditions anyway out of a sense of propriety.

"We think now of personal religions, like Christianity, Islam or Hinduism, that require belief in a deity or deities, or a moral code," Dark told Live Science. "But classical paganism did not require such beliefs. It was more ritual — so as long as one did the right thing, at the right time and in the right way, whether you believed it or not was neither here nor there."

2. The city limits

Ancient Rome had formal city limits, bounded by a strip of land called the "pomerium." No one was allowed to build in this area, which was marked by sacred stones called "cippi," Live Science previously reported. As the city grew, the pomerium was extended and new cippi were added to delineate it.

Breaking conventions inside the pomerium was considered a serious offense to the gods. No weapons were allowed there, although priests gave dispensations for the bodyguards of magistrates and soldiers taking part in one of the many "triumphs" granted by the Roman senate — a name that meant "old men" and was a ruling assembly of hundreds of the wealthiest citizens — to military commander or emperor who'd won a victory.

In particular, magistrates of the city — the officers elected for a year for various tasks, including the consuls who held the highest posts in the Roman Republic — were required to consult what were called the city auspices ("auspicia urbana") whenever they crossed the pomerium. This was a small ceremony by a priest, supposedly foretelling good or bad luck, which according to the superstition could be fatal to neglect. The Roman politician and author Cicero relates that in 163 B.C. the consul Tiberius Gracchus forgot to take the city auspices a second time after crossing the pomerium twice in the same day and that his failure led to the sudden death of an official who was collecting votes.

3. Augury

Augury was the practice of divining the future by studying the behavior of birds, such as the direction they flew or how many there were. Many Romans took augury very seriously, and it featured prominently in the affairs of the Roman state.

The first-century A.D. Roman natural philosopher Pliny the Elder attributed the invention of augury to a mythological Greek king, but historians note that the ancient Egyptians had a similar practice. Augury was performed by specialist priests called "augurs." The idea was that the behavior of birds reflected the will of the gods manifested in the natural world, so the will of the gods could therefore be determined by carefully watching the behavior of birds, according to Pliny.

A myth written down by the second-century A.D. Greek and Roman historian Plutarch tells that Romulus — the legendary founder of Rome — and his twin brother Remus resolved an argument over where to site the city by observing the flight of birds. Remus saw six vultures, but Romulus saw 12 — so the city was built where Romulus wanted, around the Palatine Hill. Augury was integrated into the official religion of pagan Rome, and the "auspices" of augury were consulted at times of national crises and war. An 18th-century French history based on classical sources records that Roman priests kept a flock of sacred chickens, which supposedly reflected the will of the gods by feeding on the grain given to them: If the sacred chickens ate it heartily while stamping their feet, then the augury was favorable; but if they refused to eat it, the augury was bad. The history notes that if a positive augury was sought, the sacred chickens might not be fed for a while first.

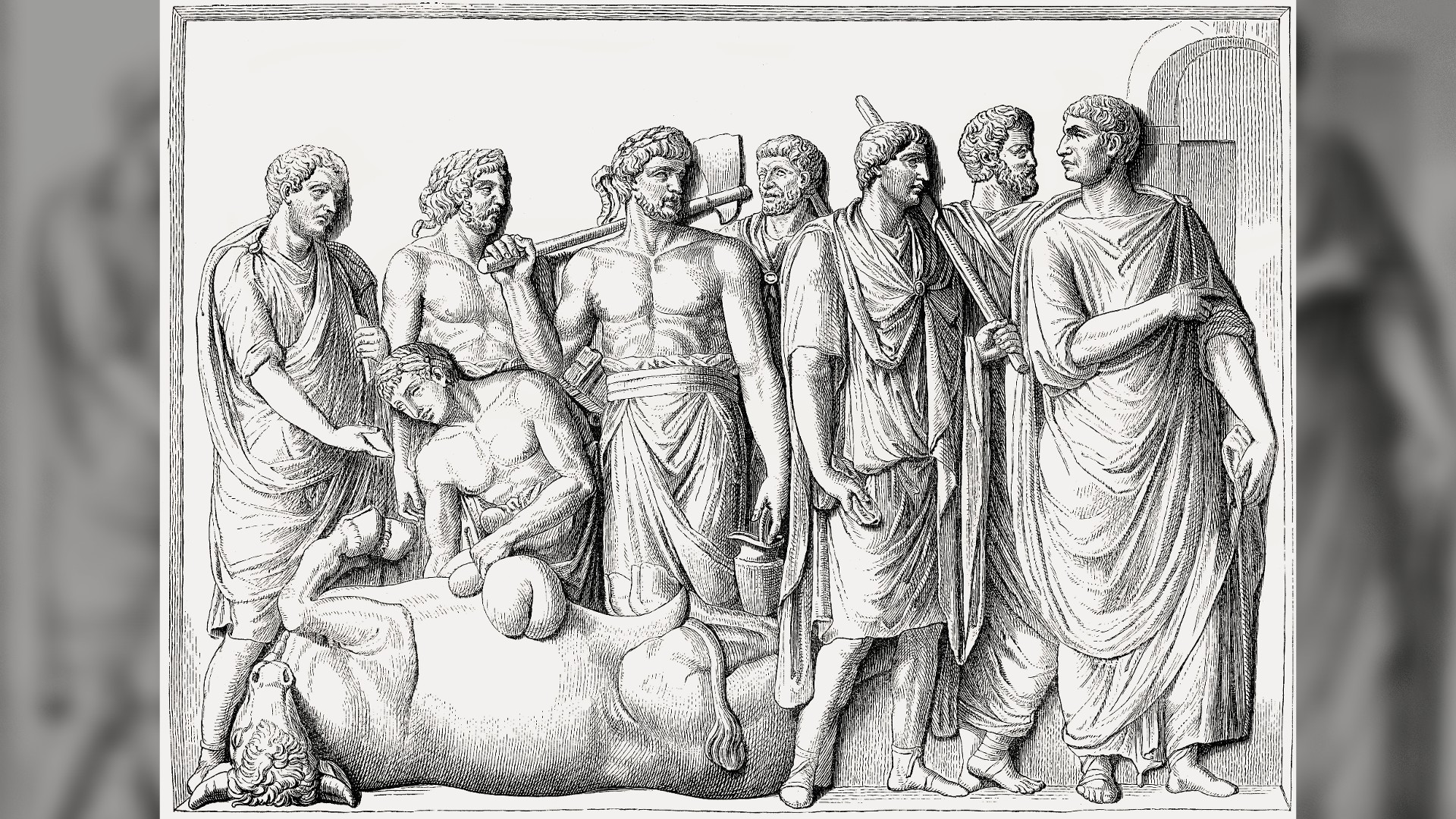

4. Haruspicy

If ancient Romans really wanted to know what was going to happen, they might turn to haruspicy — the divination of the future by examining the entrails of animals — which was considered much more accurate than augury. The ancient Romans attributed haruspicy to the Etruscans, who had lived in northwestern Italy for many centuries and had a profound influence on Roman culture. (In fact, some historians suggest that Rome was founded by Etruscans, Science reported in 2021.) A specialist in haruspicy was called a "haruspex," and Etruscan haruspices were considered especially adept. But historians note that the ancient Babylonians and others had similar practices.

The idea behind haruspicy was that the internal organs of animals — usually sheep or poultry, but sometimes oxen — that had been sacrificed to the gods could be a medium for their messages. The liver of a sacrificed animal was the most important organ because it was considered the site of the soul, but the animal's heart, lungs, kidneys, spleen and intestines were also examined. Each organ was assessed for its general condition, such as "shiny and full" or "rough and shrunken," while great importance was placed on whether the liver had a bump called the "head of the liver," or"caput iocineris." Not having this feature meant the divination was especially unfavorable, but only a skilled haruspex could find any meaning in the entrails. Models of livers were also made, presumably for reference, that showed what the various sections of the organ might portend; the most famous of these is the bronze Liver of Piacenza, an Etruscan artifact from about 400 B.C. discovered in northern Italy in 1877.

5. The Vestal Virgins

The Vestal Virgins were priestesses of Vesta — the Roman goddess of hearth, home and family — and they represented the city's purity. The institution was founded by Numa Pompilius, the second Roman king (after the legendary Romulus), who may have ruled from 715 B.C. to 672 B.C. and established the customs and laws of the new state. (According to tradition, Rome had seven kings before the Roman Republic was established at the start of the fifth century B.C.) Being a Vestal Virgin was considered a great honor, and it's said that families boasted if one of their relatives had become one. They had several assistants, including personal hairdressers for each priestess who maintained their hair in a unique formal style with braids and ribbons that took several hours to achieve.

The Vestal Virgins joined as girls and took a vow of chastity for 30 years; their most important role was to keep a fire in the temple of Vesta always burning. Vestal Virgins were considered sacred and any attempt to hurt or kill them was punished by death. This caused problems whenever any of the Vestal Virgins broke their vow of chastity — something that was seen as disastrous for the Roman state and which happened surprisingly often. To get around the prescribed penalty, the Romans devised the solution of lowering a condemned Vestal Virgin into an underground room with enough food to last them a few days and then walling them up; eventually, they would starve to death, and it was held that the starving, not being buried alive, had killed them. Plutarch notes, however, that Vestal Virgins who had maintained their chastity for 30 years could retire on a pension and were allowed to marry; many Romans believed marrying a former Vestal Virgin would bring luck and prosperity, and some men divorced their wives to do so.

6. The left hand

One peculiar Roman superstition was a belief that the left-hand side was evil, while the right-hand side represented good. That's shown by the modern English word "sinister," meaning something gives an impression of evil, which comes from the Latin word "sinister," meaning "on the left side."

A possible origin for this belief among the Romans may lie in the earlier belief among the Indo-Europeans, who between about 9,000 and 6,000 years ago spread into Europe from Asia and may have been the ancestors of the Romans. According to author Anatoly Liberman, the Indo-Europeans believed prayers should be addressed to the sun as it rose in the east. That would have placed the left hand at the north while making a prayer; and the direction north represented evil because it was thought to be the location of the Indo-European underworld, or "kingdom of the dead." Over time the left-hand side came to be seen as evil, rather than the direction north. The Romans shared their superstitious mistrust of the left-hand side with other descendants of the Indo-Europeans, including the ancient Greeks, Germans and Celts.

Whatever the origin of the superstition, it became part of Romans belief. The Latin word "sinister" was used in Roman augury, where the Greek practice of considering the left to be unlucky resulted in an unfavorable omen if birds flew to the left — and so "sinister" came to mean "harmful" or "adverse." Left-handed people were considered untrustworthy, and the Roman superstition may be the origin of the idea of "waking on the wrong side of the bed" (the left side). It's also said that noble Romans employed "footmen" to enter a house before them using their right feet.

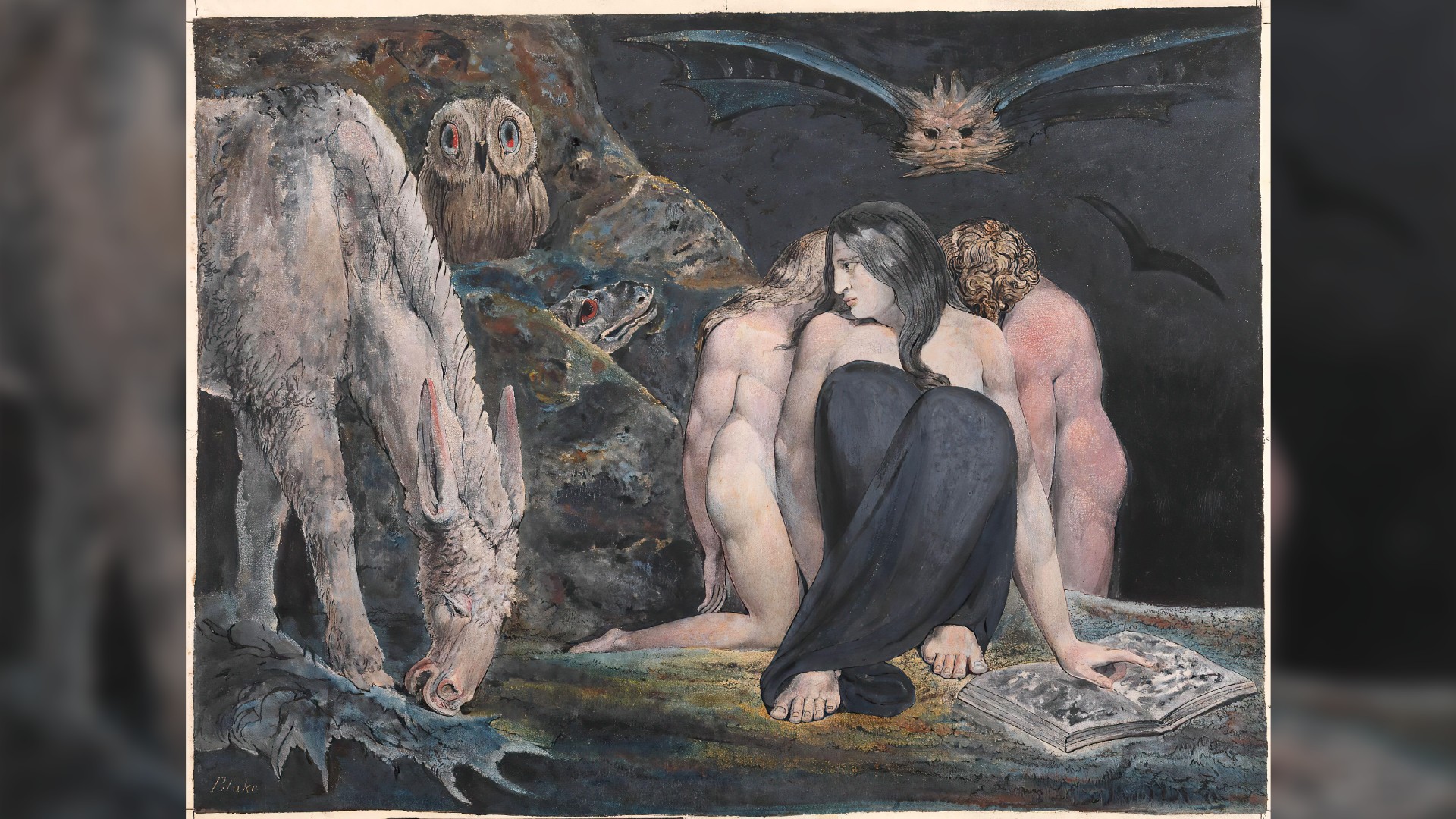

7. Spells, witches, curses and miracles

Like people in other ancient civilizations, many ancient Romans believed in magic. Ancient writings suggest that professional witches worked in Rome, and the second-century A.D. author Apuleius wrote a detailed description of one casting an evil spell, equipped with "spices of all sorts, the remains of ill-omened birds, and numerous pieces of mourned and even buried corpses: here noses and fingers, there flesh-covered spikes from crucified bodies …"

Dark noted that even in the late Republic era, from about the second century B.C. until about 31 B.C., when Augustus took power, the city of Rome was filled with people from other places who would have brought their local forms of magic. "There was a huge diversity of beliefs," he said.

One Roman specialty was "curse tablets," which were inscribed on thin sheets of lead and then buried, thrown into a well or pool, placed in a stone crack or nailed to the wall of a temple. They were typically addressed to infernal gods — like Pluto, Charon or Hecate — and often called for violent divine punishments in response for trivial slights, Dark said. According to BBC News, more than one hundred curse tablets have been found in archaeological digs at the English city of Bath, which in Roman times was a resort famed for the healing powers of its hot springs. One tablet, featuring a curse for a stolen swimsuit, addressed the goddess of a temple there: "I give to your divinity and majesty [my] bathing tunic and cloak. Do not allow sleep or health to him who has done me wrong, whether man or woman or whether slave or free, unless he reveals themselves and brings those goods to your temple."

Many ancient Romans were devout believers in what they saw as signs from the gods, especially unusual natural occurrences. Roman historians such as Livy and Suetonius, for example, relate such "prodigies" matter-of-factly in their writings, including untimely famines; eclipses of the sun and moon; the birth of deformed animals, such as a foal with five legs; an unborn child who cried "triumph" from his mother's womb; and "blood" rain in distant cities.

Dark said such "signs from God" and the later "miracles" were some of the few aspects of Roman superstition to survive the Roman Empire's transition to Christianity from the fourth century. "Christianity was dead against magic and that sort of thing, but people were prepared to accept that there could be signs that could foretell things," he said. An example was the Vision of Constantine, who, before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in A.D. 312, reportedly saw the Christian symbol of a cross in the sky and the words "In Hoc Signo Vinces" or "By this sign shall you conquer." The vision was reinforced by a dream a few days later, and Constantine ordered his troops to inscribe Christian symbols on their shields, won the decisive battle and thereafter converted from paganism to Christianity.

Originally published on Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.