Ancient sanctuary used by Roman soldiers nearly 2,000 years ago found in the Netherlands

The complex had altars for Mercury, Jupiter and Hercules.

One of the most extensive ancient Roman temple complexes in northern Europe, which includes sacrificial altars used by soldiers on a far frontier of the Roman Empire, has been unearthed in the Netherlands.

The first century A.D. site — known as a temple sanctuary — was located near the fork of the Rhine and Waal rivers and a short walk from Roman forts along the Lower German Limes, which was then the northernmost border of the empire. It now lies near the Dutch city of Zevenaar in the eastern Gelderland region, near the border with Germany.

The sanctuary consisted of at least three large temples and many smaller altars dedicated to particular Roman gods and goddesses, and would mainly have been used for sacred vows by Roman soldiers stationed at the nearby forts, project leader Eric Norde, an archaeologist at the Dutch archaeology agency RAAP, told Live Science.

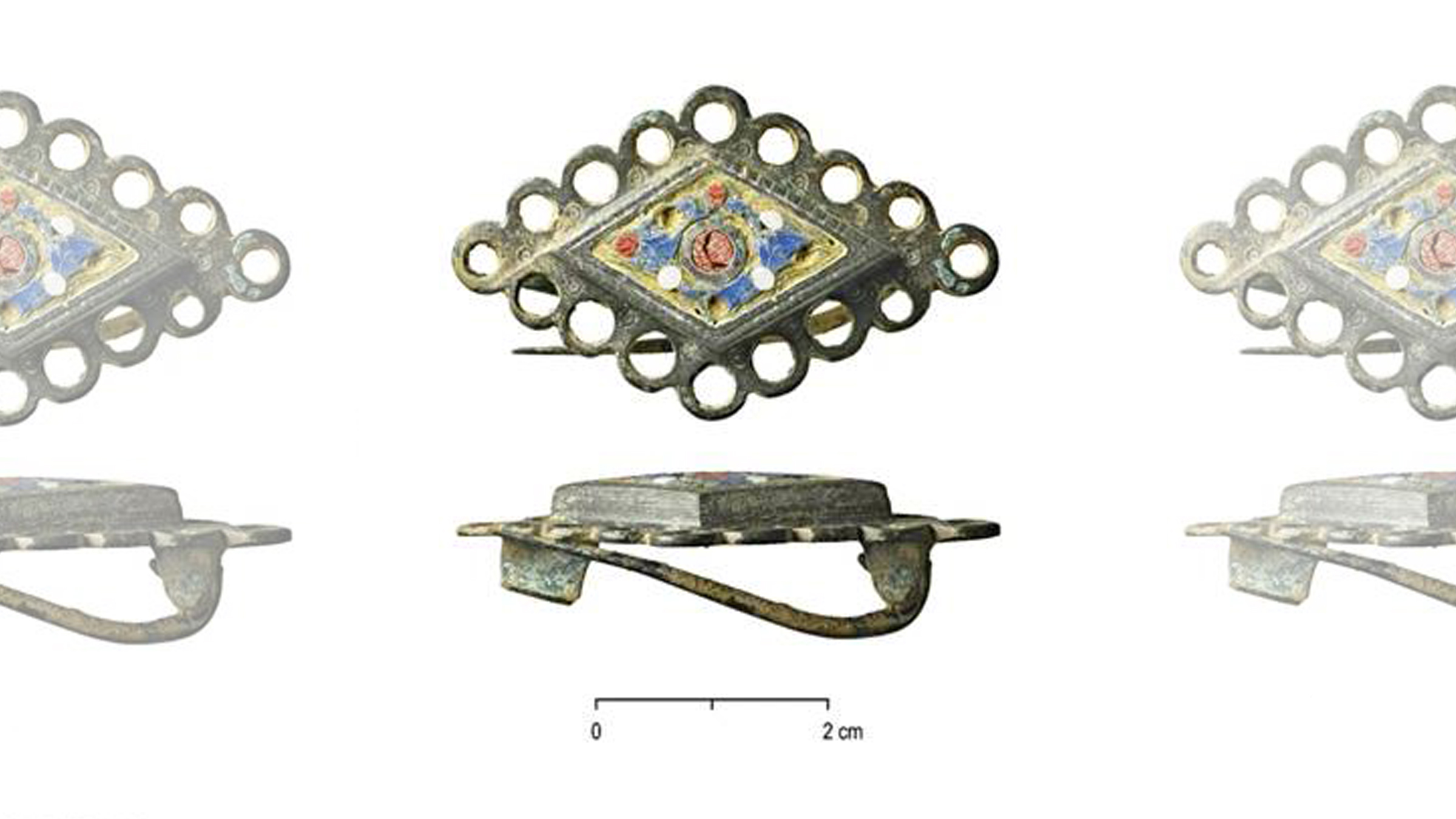

Hundreds of artifacts have been found at the site, including coins and jewelry; while the tips of spears and lances, and the remains of armor and horse harnesses, emphasize its military nature, he said.

Related: 7 Roman inventions: Incredible feats of ancient technology

The discoveries give a glimpse of the lives of soldiers stationed on the frontiers of the empire, far from the Roman heartlands.

"It's the best-preserved Roman sanctuary in the Netherlands, and perhaps in a much larger area," Norde said. "It's quite extraordinary."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The central government of the Netherlands and the provincial Gelderland government have contracted RAAP to excavate the site, which was first unearthed during commercial clay extraction works in 2021, according to a statement by the Dutch cultural ministry. The clay extraction has been stopped for the excavations but is continuing nearby, and so the archaeological site is closed to the public for now.

Votive altars

The temple sanctuary was built on a slight hill near the fork of the rivers; the hill was then made slightly higher. A stone staircase led down to the water and there was also a large well at the site, Norde said. The temples were also surrounded by several hearth pits, which appear to have held large sacrificial fires.

The major temples in the sanctuary were colorfully painted with frescoes and had tiled roofs. Stamps on the tiles show they were often made by the soldiers — a commercial specialty of the Roman legions, according to a report by Deutsche Welle, a German state-owned news outlet.

But the sanctuary is also notable for its many votive altars outside the main temples, which supplicants would have used for pouring wine and offering animal sacrifices during prayers and vows.

Norde said the votive altars were dedicated to several different Roman deities, including Mercury, the god of messages, money, and magic; Jupiter-Serapis, an avatar of the chief god that originated in ancient Egypt; Hercules Magusanus, an amalgamation of the Roman demigod Hercules (Heracles in Greek) and an unnamed Germanic god or hero; and the Iunones, a group of goddesses worshiped mainly in Roman Gaul.

Each votive altar bore a Latin inscription naming the gods or goddesses it was dedicated to and the Roman soldier who'd paid for it to be placed there, along with his rank and the cohort (a group of about 500 soldiers) of which legion (numbering about 5,000 soldiers) he belonged to.

Norde said the altars seem to have been placed by senior officers at the Roman forts, as thanks to their gods for fulfilling a wish — perhaps winning a battle, or surviving a stay in the northern regions far from home.

The inscriptions always end with an affirmation by the soldier, using the formal phrase "Votum Solvit Libens Merito" — Latin for "He pays the vow, willingly and with good reason."

Far frontier

The newly-found sanctuary lies on what was once the northern border of the Roman Empire, known as the Lower German Limes and marked by a series of fortifications along the Rhine, between what the Romans knew as Germania Inferior and Germania Magna, or Lower Germania and Greater Germania.

Related: 8 powerful female figures of ancient Rome

In the first century A.D. its westernmost point was a North Sea mouth of the Rhine, now near the Dutch city of Leiden; and it continued along the western shore of the giant river until near the German town of Bad Breisig, south of Bonn. Another series of fortifications, known as the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes, then started on the opposite shore and continued south and east to the Danube.

Many of the surviving structures in the Netherlands and Germany are now listed by the United Nations cultural agency UNESCO as World Heritage Sites, and experts hope that the temple sanctuary near Zevenaar will eventually be included, Norde said. For now, several objects recovered from the site are on display in the Netherlands at the Valkhof Museum in the nearby city of Nijmegen.

Archaeologists are still working to precisely date the various structures, but it seems the sanctuary was in use from about the first century A.D. until the later parts of the third century A.D., when the Roman control of its northern provinces began to falter under Germanic invasions, Norde said.

The sanctuary would have mainly served the nearest Roman forts, as well as soldiers coming from farther away."We have many troops mentioned in the votive altars, so it's also possible that the sanctuary had some kind of regional function," he said.

As well as the remains of the temples, altars and artifacts, the archaeologists have unearthed the remains of many sacrificial animals — often birds such as chickens, but also larger animals like pigs, sheep and oxen.

"We have found many, many traces of offerings made by the soldiers, and many remains of foods offered to the gods," Norde said. "So we can take a look at daily life at the temple site."

Originally published on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.