Ancient sacred pool lined with temples and altars discovered on Sicilian island

The pool would have reflected the stars.

A 2,500-year-old artificial lake on a Sicilian island might have been a sacred pool that aligned with and reflected starlight from certain constellations, not an inner harbor built for military or trading purposes, as was previously thought, archaeologists say.

In its heyday, this sacred pool would have been the centerpiece of a giant sanctuary holding temples and altars that honored several deities, a new study suggests. The Phoenicians built the pool on the island city of Motya in around 550 B.C., following a devastating attack by Carthage.

"It was a sacred pool at the centre of a huge religious compound," not a harbor, study researcher Lorenzo Nigro, a professor of Near Eastern and Phoenician Archaeology at Sapienza University of Rome, said in a statement.

Nigro announced this interpretation of the site following nearly 60 years of archaeological work at Motya, which included discoveries of star-gazing instruments and statues of deities associated with astronomy, according to the study, published online Thursday (March 17) in the journal Antiquity.

Related: Photos: Ancient Greek shipwreck yields Antikythera mechanism

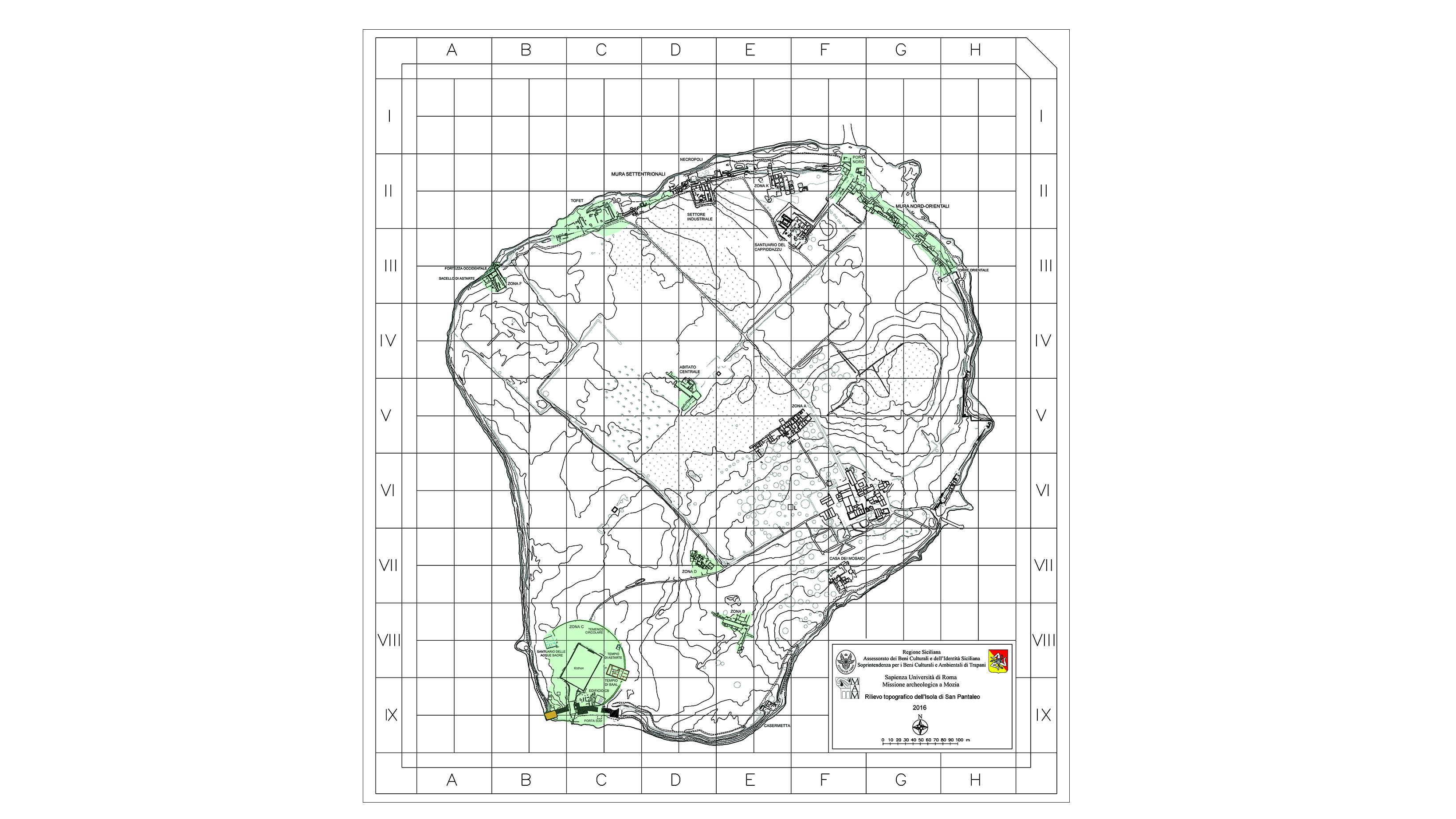

Motya, a small island that covers an area of just under 100 acres (40 hectares), sits off the western coast of Sicily. Bronze and Iron Age populations thrived there due to the abundant supply of fish, salt, fresh water and its protected location within a lagoon, Nigro wrote in the study. In the eighth century B.C., Phoenicians began settling there and integrating with locals, bringing their distinctive West Phoenician culture to the island.

Just 100 years later, the settlement had grown into a bustling port city with a trade network stretching across the central and western Mediterranean. This brought Motya into conflict with Carthage, a rival power with Phoenician roots on the North African coast. In the mid-sixth century B.C., Carthaginian forces demolished Motya.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But Motya bounced back. The population quickly rebuilt the city, including the enigmatic artificial basin, which archaeologists discovered in the 1920s. The basin looked similar to the Kothon, an artificial harbor that served as a military port at Carthage, so it was previously thought to be one, too. A later interpretation in the 1970s suggested the basin served as a place to repair ships.

However, archaeological work undertaken between 2002 and 2020 at the stone-lined basin tells a different story. Several clues found at the pool — which spans an area of 172 by 121 feet (52.5 by 37 meters) — suggest it was a placid sacred pool that mirrored the stars. Previous excavations revealed a Temple of Ba'al, a god similar to the Greek god Poseidon, at the edge of the basin. If this were a harbor, the port would likely have harbor buildings, not a temple, Nigro said.

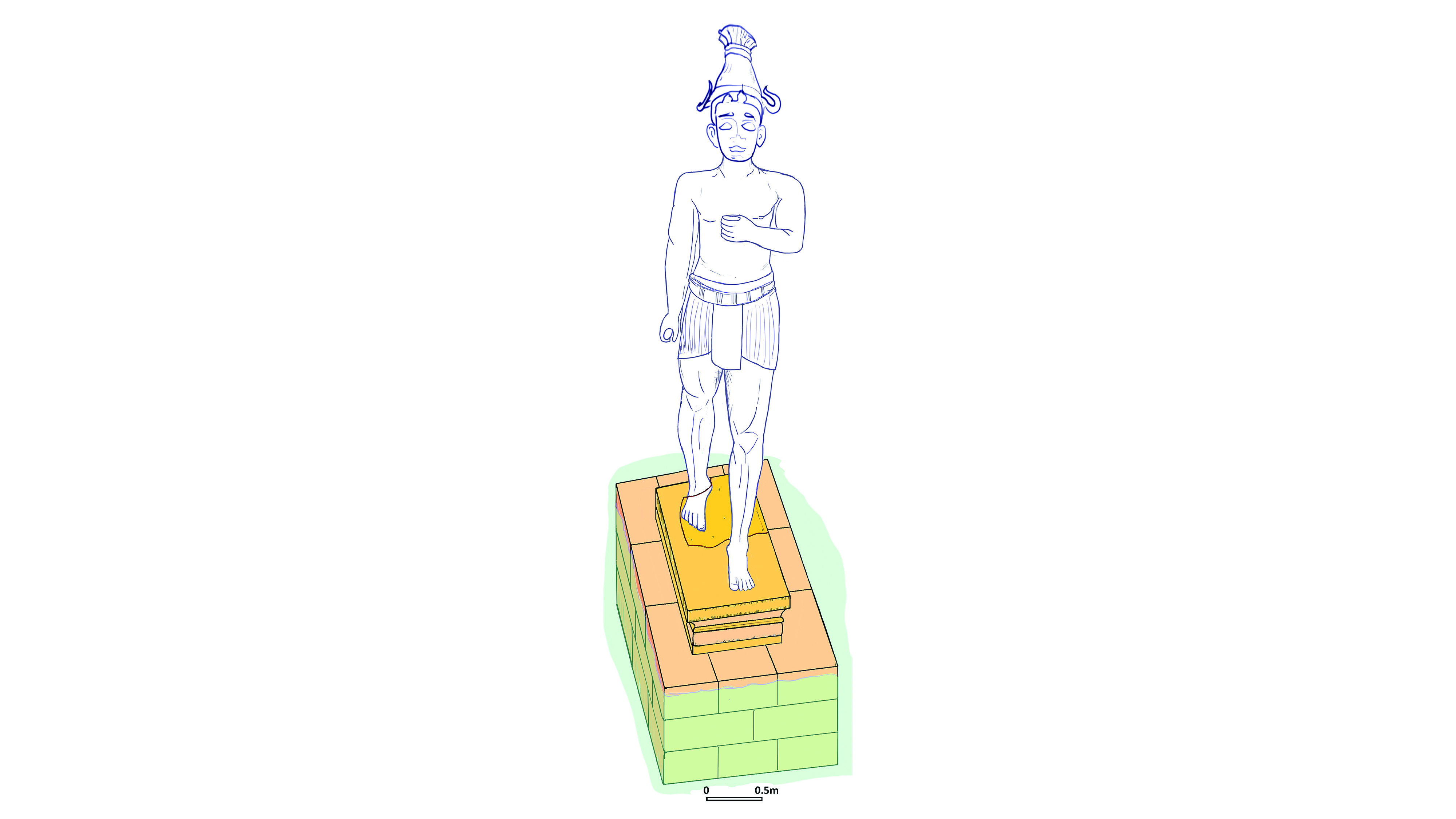

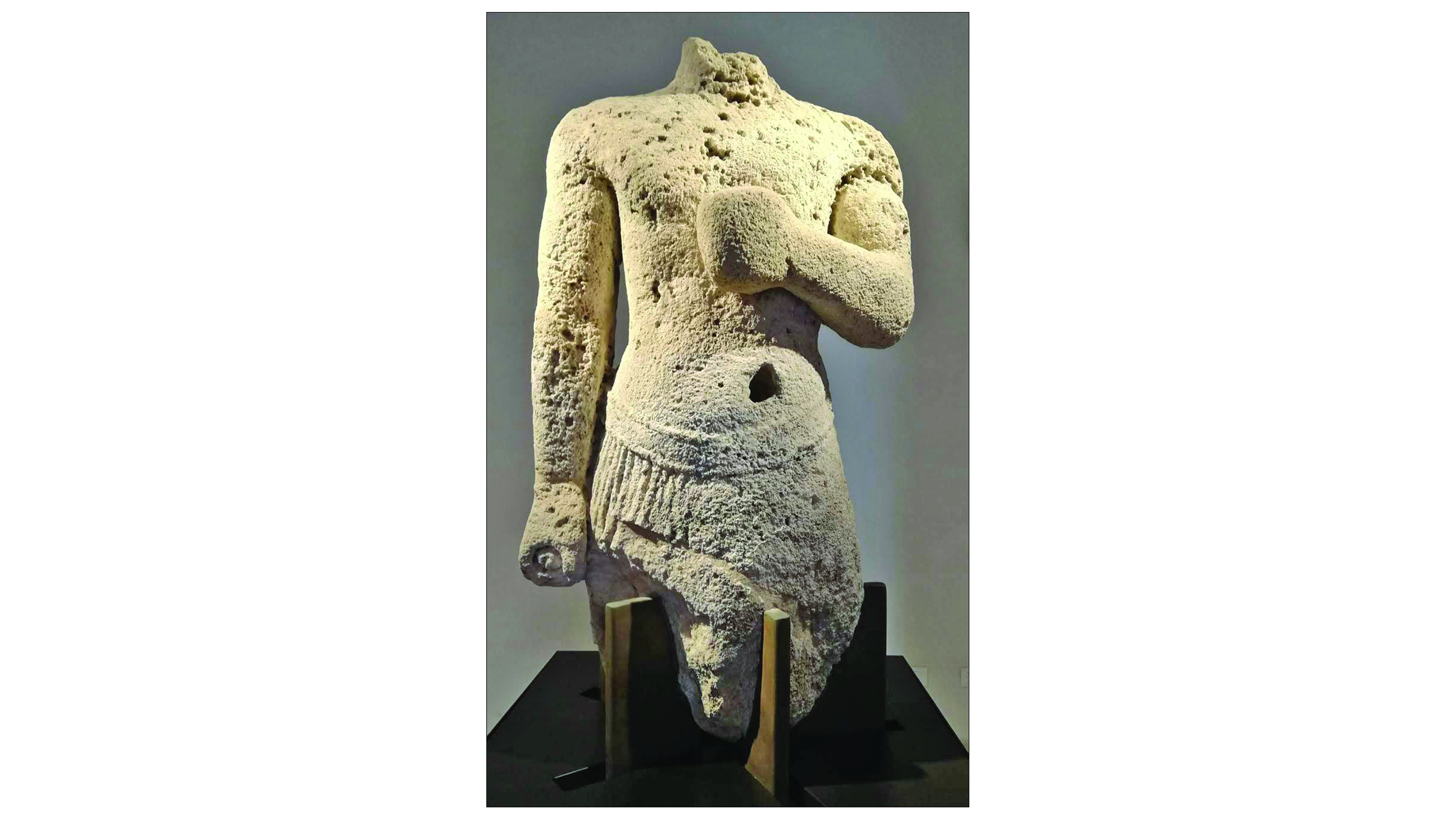

When Nigro and his colleagues drained and excavated the basin, they saw that it wasn't connected to the sea, but instead was filled by natural freshwater springs. They also found the remains of more temples around the basin, along with altars, engraved stone slabs known as stelae, votive offerings (special objects, such as figurines, that people left for religious purposes) and — as the icing on the cake — a pedestal at the center of the artificial lake that once held a large statue of Ba'al.

"Two clues were decisive: the unearthing of a solid wall closing the pool in the sea direction and the discovery that the pool actually collected freshwater" from an underground aquifer, Nigro told Live Science in an email. "It was a reservoir of pure water for the temple and the sails crossing the Mediterranean."

Moreover, the archaeologists found that the pool would have reflected important constellations. The spatial layout of the sanctuary may have represented a "celestial vault," Nigro wrote in the study. There is a niche in the sanctuary that marks the position of Capella (Alpha Aurigae), the sixth-brightest star in the night sky, when it rises to the north during the autumn equinox, he said. Meanwhile, a stela in the enclosure's south marks Sirius (Alpha Canis Major), the brightest star in the night sky, when it rises to the south during the autumn equinox, he found.

Related: Image gallery: Stunning summer solstice photos

"Finally, Orion, identified with the Phoenician god Ba'al, rises to the east-southeast at the winter solstice; Motya's Temple of Ba'al is orientated in this direction," Nigro wrote in the study.

Archaeologists also found the bronze pointer of an astrolabe, an ancient navigation tool, during the excavation of the Temple of Ba'al, he wrote in the study. Another discovery included the worn statue of a dog-headed baboon, a personification of the Egyptian god Thoth, who was associated with astronomy and often featured in zodiacs.

The evidence supports the new interpretation that the basin was a sacred pool, not an inner harbor for ships, said Michele Guirguis, an associate professor of Phoenician-Punic archaeology at the University of Sassari in Italy, who was not involved with the study.

"Personally, I find myself in total agreement with the interpretations proposed by Nigro," Guirguis told Live Science in an email. "If Lorenzo Nigro had not had the courage to 'empty' the kothon of water and mud, he would never have discovered the vein of drinking water, the real 'treasure' that the ancient peoples sought and protected.

"From this we should draw a precious lesson, which pushes us to safeguard the most relevant commodity that we could ever find on the planet in any era of human development, the freshwater."

For now, the sacred pool is once again filled with this precious resource. After finishing the excavation, the team filled the basin with water and put a replica of Ba'al on the pool's center pedestal.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.