Remains of a Massive Jurassic 'Sea Monster' Found in a Polish Cornfield

The beast had a bite more powerful than that of T. rex.

Paleontologists in Poland recently unearthed the jaws and teeth of a monstrous pliosaur, an ancient marine reptile with a bite more powerful than that of Tyrannosaurus rex.

Pliosaurs, the biggest of the Jurassic period's ocean predators, lived around 150 million years ago. Researchers found fossils of this enormous carnivore in a cornfield in the Polish village of Krzyżanowice in the Holy Cross Mountains, along with several hundred bones of crocodile relatives, ancient turtles and long-necked plesiosaurs — cousins of pliosaurs — according to a new study.

Jurassic pliosaur fossils have been found in only a few European countries, and this is the first time bones of the massive marine predator have emerged in Poland, lead study author Daniel Tyborowski, a paleontologist with the Polish Academy of Sciences' Museum of the Earth in Warsaw, said in a statement.

Related: Image Gallery: Ancient Monsters of the Sea

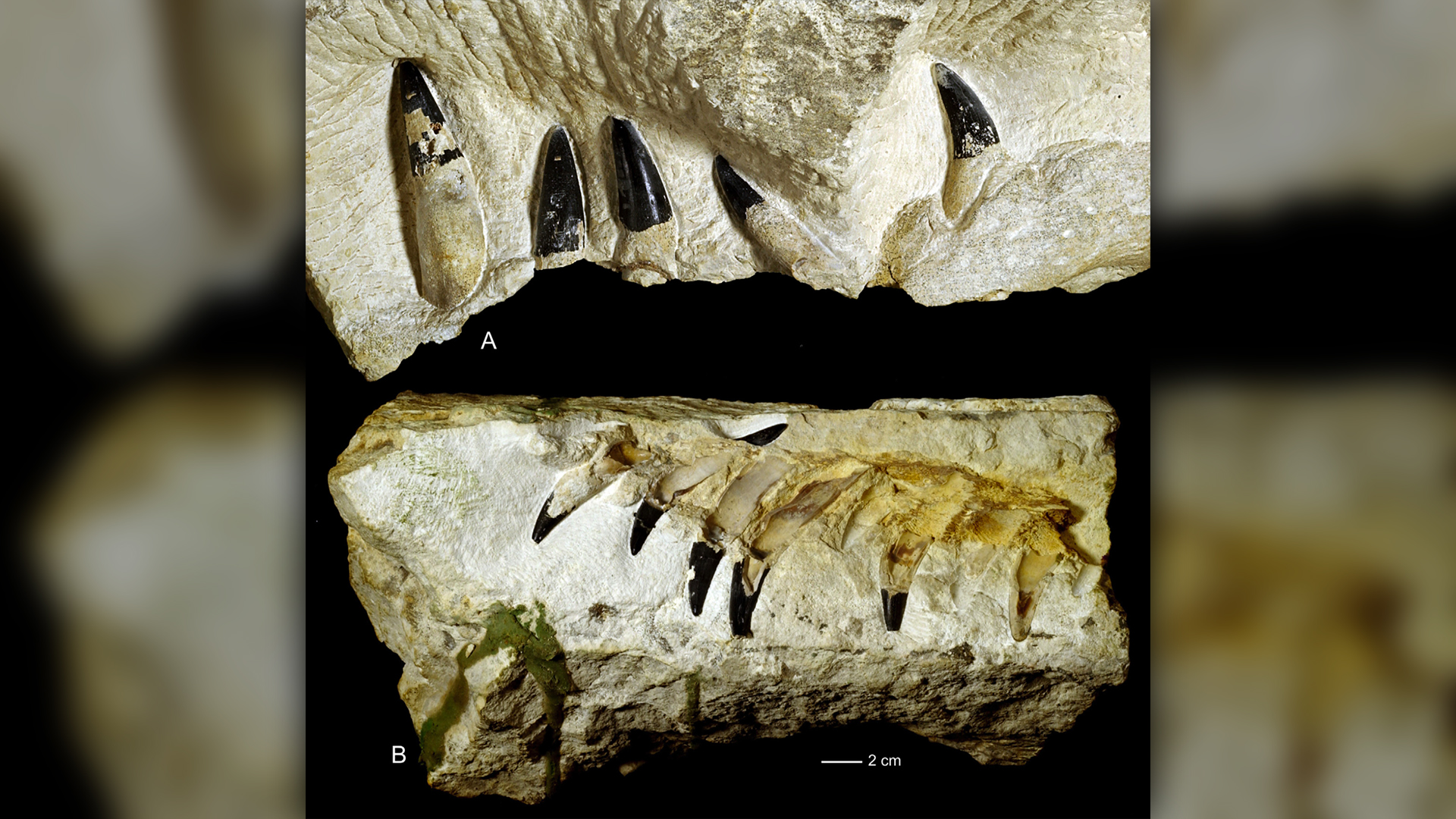

A limestone block found at the site in Poland held cone-shaped teeth and fragments of an upper and lower jaw that the scientists identified as belonging to a pliosaur, dating between 145 million and 163 million years ago. The biggest tooth measured about 3 inches (68 millimeters) from crown to tip. Another large, isolated tooth — also thought to belong to a pliosaur — measured about 2 inches (57 mm) in length, according to the study.

Pliosaurs lived alongside dinosaurs (though not T. rex, which didn't appear until around 70 million to 65 million years ago, during the Cretaceous period). "They measured over 10 meters [32 feet] in length and could weigh up to several dozen tons," Tyborowski said in the statement. "They had powerful, large skulls and massive jaws with large, sharp teeth. Their limbs were in the form of fins." Unlike plesiosaurs — which had long, graceful necks and small heads — pliosaurs had massive heads supported by thick, powerful neck muscles that helped them crush the bones of large prey.

One known pliosaur species, Pliosaurus funkei, had a 7-foot-long (2 m) skull and a bite estimated to be about four times as powerful as that of T. rex. These apex predators would have been at the top of the food chain in their marine ecosystems, feasting on crocodilians, plesiosaurs, turtles and fish, the study authors reported. Six pliosaur species have been described to date. However, it is not yet known to which species the new fossils belong.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We hope that the next months and years will bring even richer material in the form of bones of large reptiles," Tyborowski said in the statement.

More than 100 million years ago, this mountainous region was an archipelago of islands surrounded by warm lagoons, but the variety of Jurassic marine species at the mountain site also suggested that this area was a "hub" where the habitats of different groups of marine reptiles overlapped, the scientists reported.

Ancient turtles and crocodile relatives are known from Mediterranean sites; they inhabited warm waters in the Tethys Ocean, a vast sea that lay between two ancient supercontinents — Gondawna in the south and Laurasia in the north — during the Mesozoic period, 251 million to 65.5 million years ago. But pliosaurs, plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs (another type of marine reptile with long, slender jaws) are more commonly found in cooler waters farther north. Because the site in Krzyżanowice holds fossils from both warmer and cooler environments, the researchers proposed that it represents a transitional zone that was once a unique ocean ecosystem, according to the study.

The findings were published online Oct. 6 in the journal Proceedings of the Geologists' Association.

- Photos: Ancient Sea Monster Was One of Largest Arthropods

- In Photos: How Ancient Sharks and 'Sea Monsters' Inspired Mayan Myths

- Image Gallery: Photos Reveal Prehistoric Sea Monster

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.