Mini sea monster had teeth as sharp as a saw blade

Local miners found the fossils in Morocco.

A sea monster with teeth so sharp they formed a "saw-like blade," swam in the waters of what is now Morocco about 66 million years ago, a new study finds.

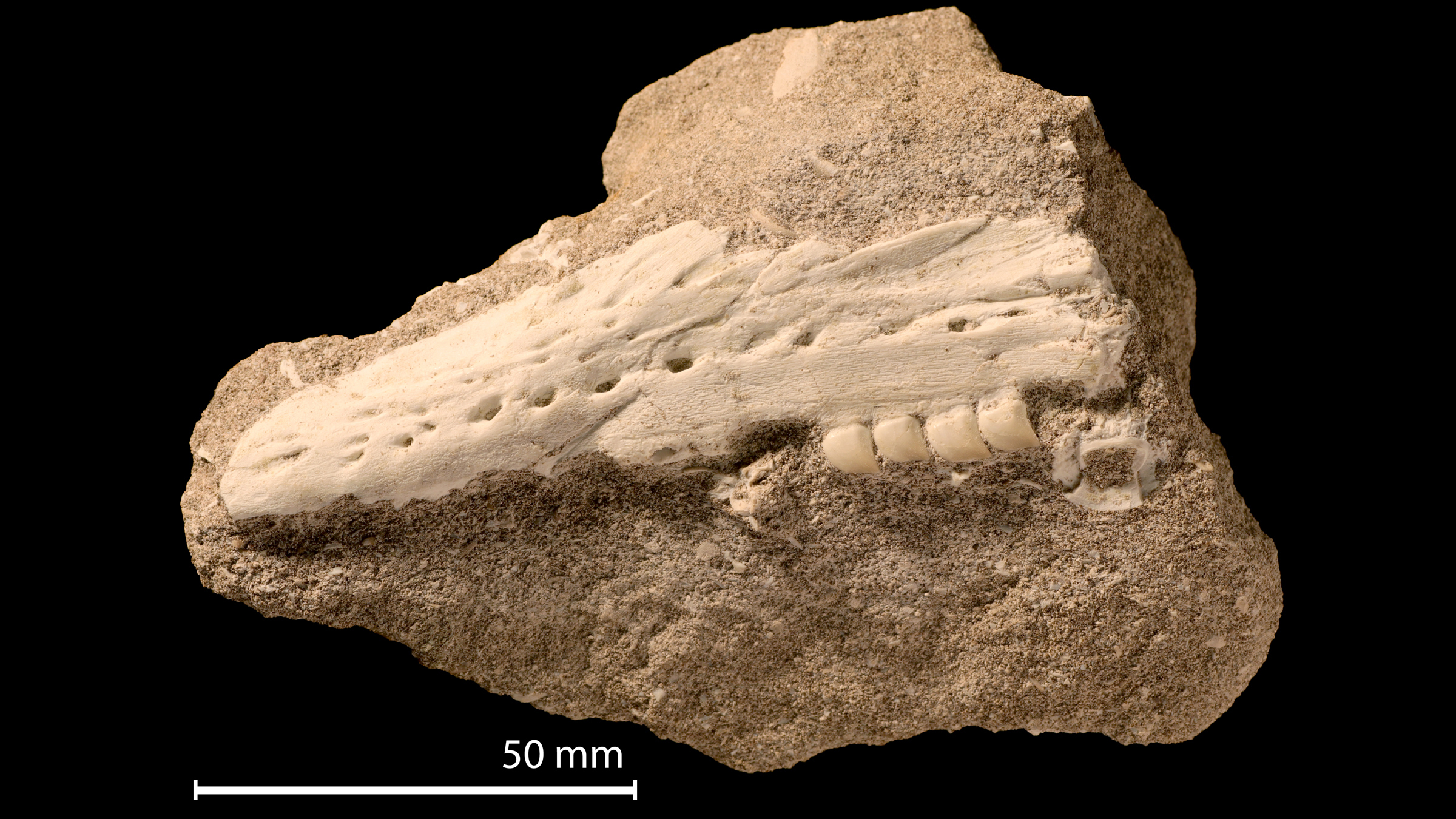

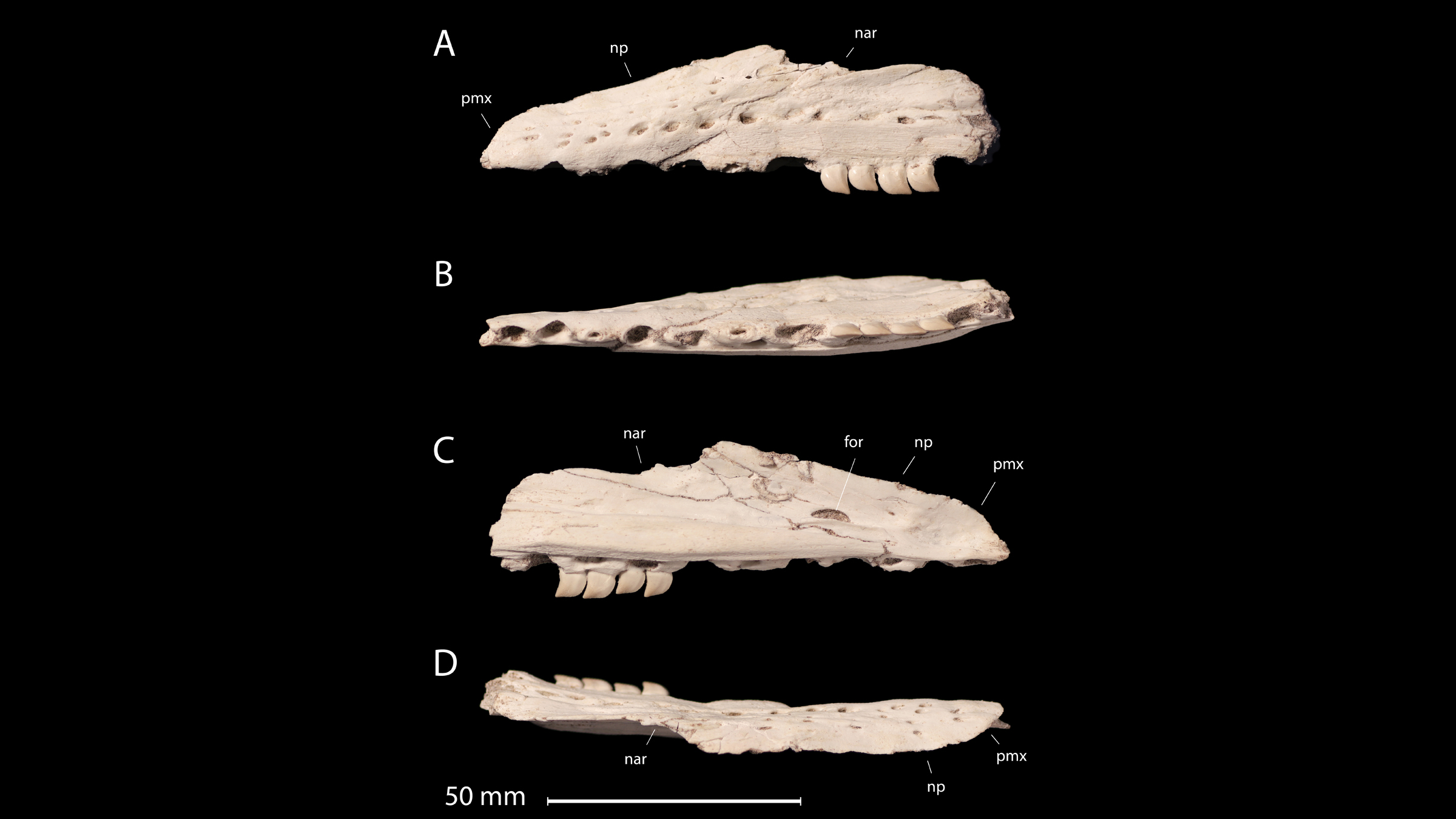

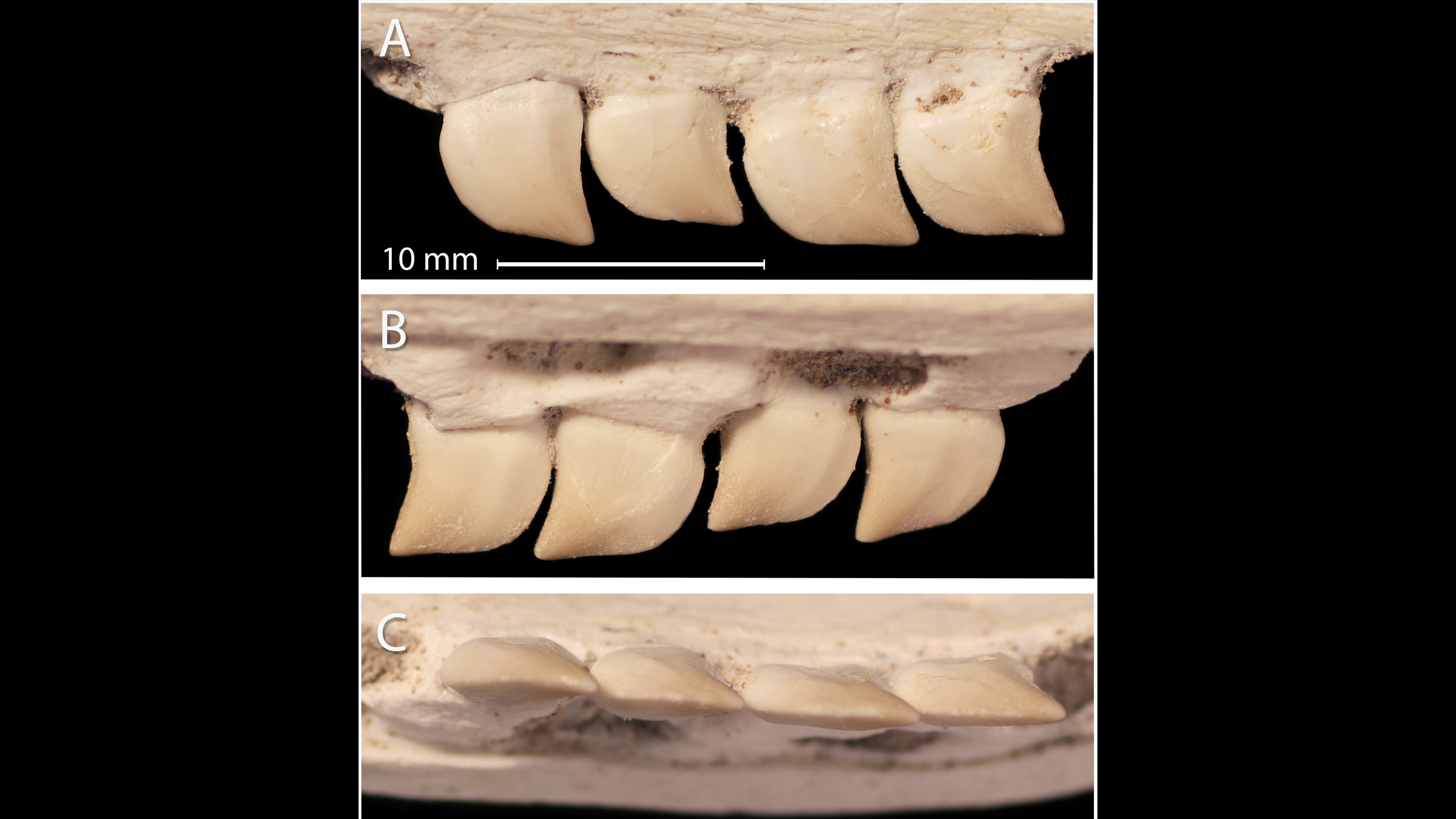

Miners discovered the remains of this creature — a lizard-like marine reptile called a mosasaur that lived during the dinosaur age — at the Sidi Chennane phosphate mine in Morocco's Khouribga province. Once researchers examined the specimen, they noticed its unique teeth, which had features never before seen in any other known reptile, living or extinct, the researchers said.

In honor of the predator's deadly yet odd pearly whites, the team named the mosasaur Xenodens calminechari, whose genus name means "strange tooth" in Greek and Latin, and whose species name translates to "like a saw" in Arabic.

Related: Image gallery: Ancient monsters of the sea

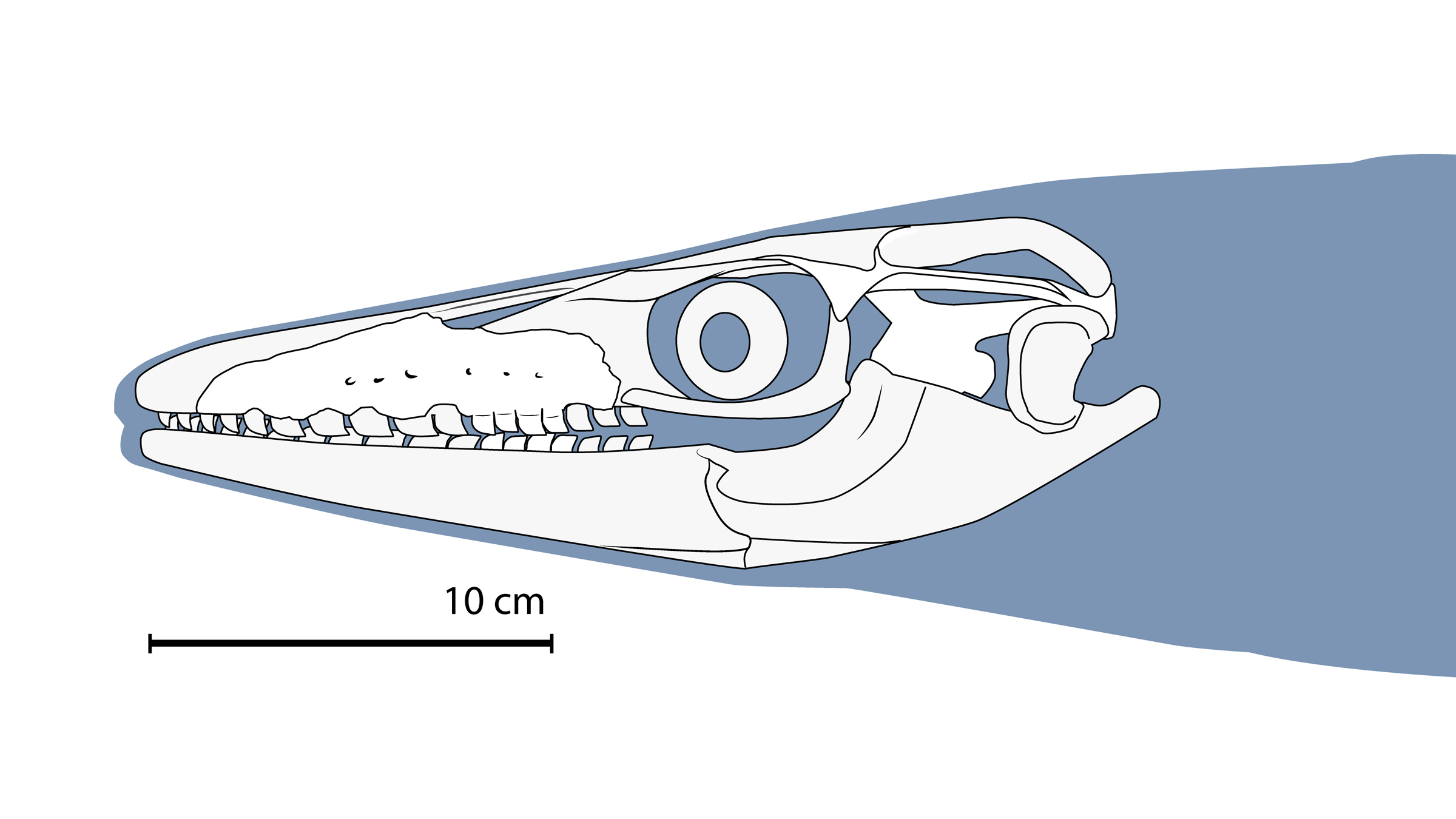

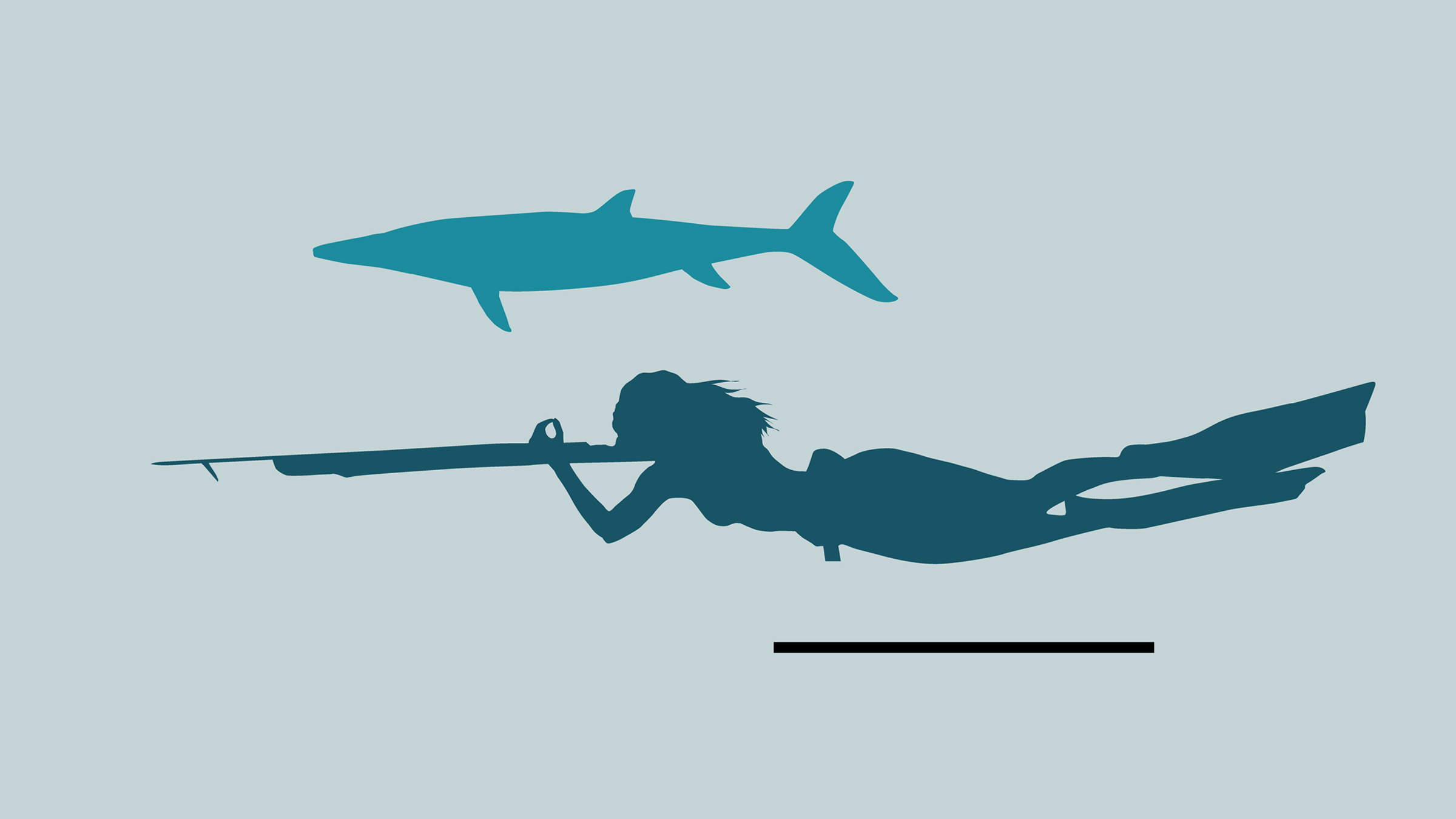

Its closely packed knife-like teeth gave X. calminechari a shark-like slicing bite and may have been key to its survival; X. calminechari wasn't large — it was about the size of a porpoise — so it likely relied on its agility and weapon-like teeth to get by.

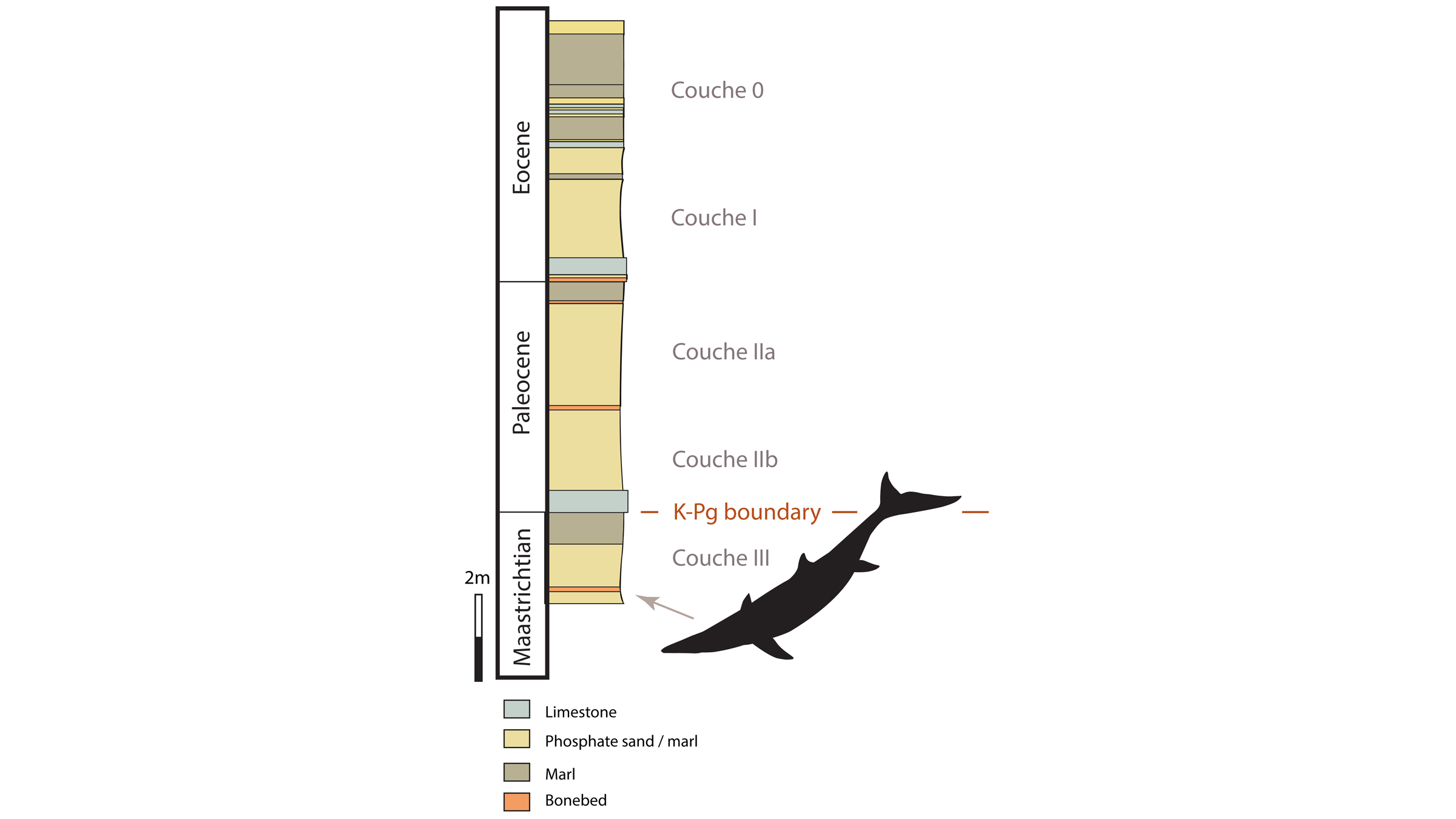

During the late Cretaceous period, when X. calminechari was alive, Morocco lay beneath a tropical sea. Those warm waters were filled with predatory marine animals, including other mosasaur species, long-necked plesiosaurs, giant sea turtles and saber-toothed fish.

"A huge diversity of mosasaurs lived here," study lead researcher Nick Longrich, a senior lecturer at the Milner Centre for Evolution at the University of Bath in the United Kingdom, said in a statement. "Some were giant, deep-diving predators like modern sperm whales, others with huge teeth and growing up to 10 meters [32 feet] long, were top predators like orcas, still others ate shellfish like modern sea otters — and then there was the strange little Xenodens."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Discover the Dinosaurs: $22.99 at Magazines Direct

Journey back to the age of dinosaurs with Live Science and uncover the secrets of some of the prehistoric world’s most remarkable beasts. From the Tyrannosaurus rex and Diplodocus to the Triceratops and Coelophysis, get up close and discover how these fascinating creatures lived, hunted, evolved and ultimately died out. Why did Stegosaurus travel in herds? Is it possible to clone a dinosaur? Find the answers to these questions and many more.

X. calminechari's unusual dentition likely gave it a unique hunting strategy, "likely involving a cutting motion used to carve pieces out of large prey, or in scavenging," the researchers wrote in the study.

"A mosasaur with shark teeth is a novel adaptation of mosasaurs so surprising that it looked like a fantastic creature out of an artist's imagination," study senior researcher Nour-Eddine Jalil, a paleontologist at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris and Cadi Ayyad University in Marrakesh, Morocco, said in the statement.

The discovery of X. calminechari also adds evidence that the marine reptile ecosystem, as well as diversity, in Morocco was thriving at the end of the Cretaceous. But it all ended when the 6-mile-wide (10 kilometers) rock smashed into Earth, causing the extinction of these marine creatures and the dinosaurs.

An advance copy of the study was published online Jan. 16 in the journal Cretaceous Research.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.