What was megalodon's favorite snack? Sperm whale faces

Ruthless megalodon snacked on whales' fat-rich noses, fossil skulls show.

If the giant, extinct shark megalodon had to pick a favorite meal, the winner would likely be sperm whales ... by a nose.

In fact, sperm whale noses were popular snacks not only for megalodon but also for other ancient sharks that preyed on sperm whales, according to a new analysis of fossil whale skulls.

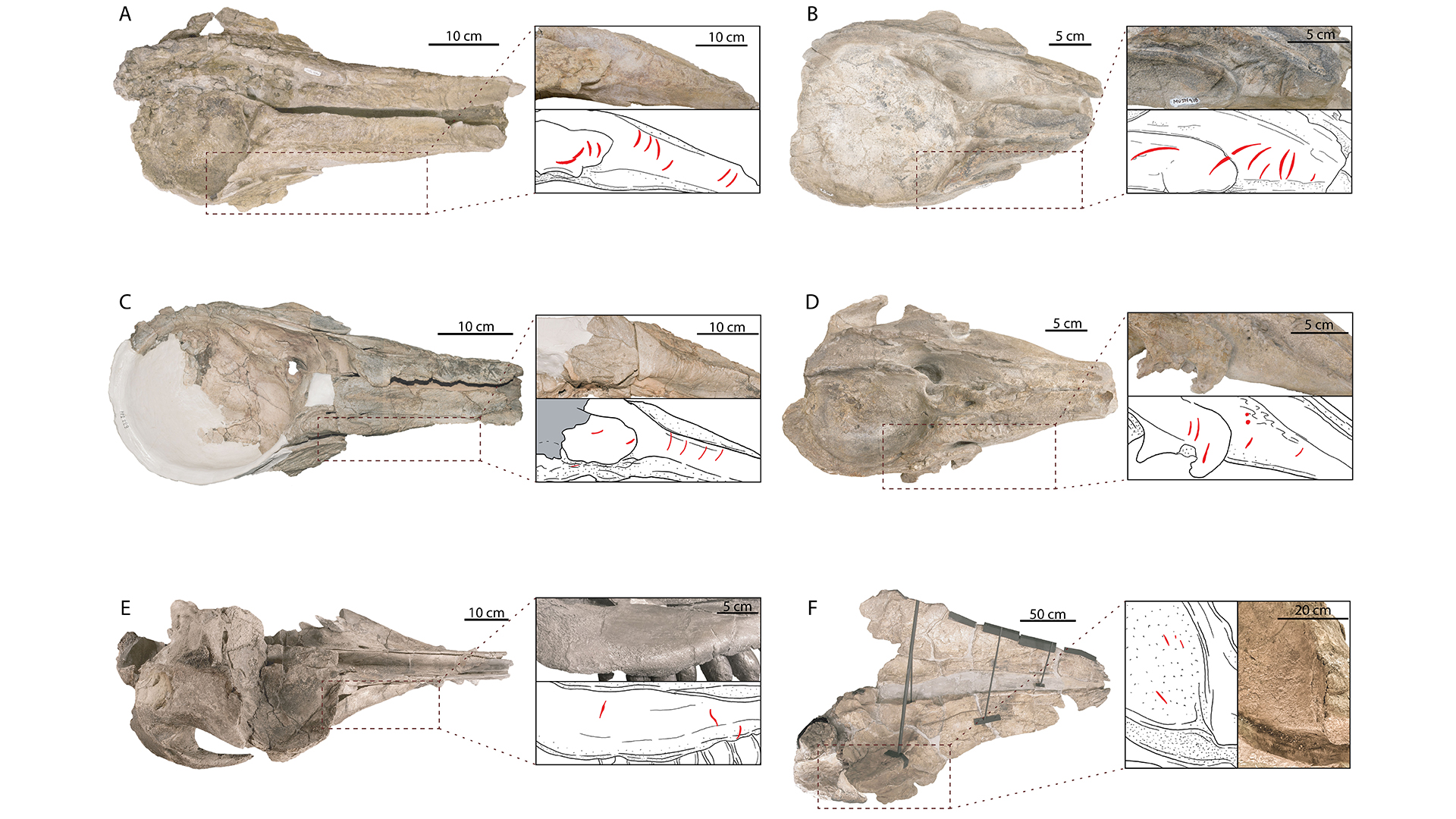

When scientists in Peru peered at a series of skulls belonging to extinct whales that lived during the latter part of the Miocene epoch (23 million to 5.3 million years ago), they found numerous bite marks left behind by multiple shark species, including the massive megalodon (Otodus megalodon) and sharks that are still around today, such as great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) and mako sharks (Isurus).

In some cases, a number of shark species had fed on the skull of a single whale in "a series of consecutive scavenging events" that left the skull scarred by more than a dozen bites. What's more, the location of the bite marks told the scientists that the sharks were targeting the whales' foreheads and noses, likely so the predatory fish could feast on the fatty organs' generous stores of nutritious blubber and oil.

Related: Giant shark, possibly a megalodon, feasted on this whale 15 million years ago

Sperm whales are the biggest toothed predators alive today. They are known for their bulky heads, and much of the space inside is taken up by enlarged nasal organs that the whales use for sound production, the scientists reported June 29 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. Two structures in this nasal network, the melon and the spermaceti, are rich in oils and fats. And bite marks in the Miocene whale skulls corresponded with the positions of these structures in modern sperm whales, the scientists discovered.

"Many sharks were using these sperm whales as a fat repository," said lead study author Aldo Benites-Palomino, a doctoral candidate at the Paleontological Museum of the University of Zurich in Switzerland. "In a single specimen, I think that we have at least five or six species of sharks all biting the same region — which is insane," he told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Three species of sperm whale swim the oceans today: the great sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus), the pygmy sperm whale (Kogia breviceps) and the dwarf sperm whale (Kogia sima). But around 7 million years ago, there were at least seven sperm whale species, ranging from small-fry species in the Kogia and Scaphokogia genera that were no more than 13 feet (4 meters) long, to enormous creatures such as Livyatan, which measured up to 60 feet (18 m) long.

And trailing after those Miocene sperm whales were plenty of ravenous shark species, just waiting for an opportunity to eat the whales' faces.

For the study, the scientists analyzed sperm whale skulls in the collection of the Natural History Museum in Lima. The skulls had been collected from the Pisco Formation in southern Peru and dated to about 7 million years ago; during the Miocene, this coastal desert region was a hotspot for marine biodiversity, the researchers reported.

The team discovered patterns of bite marks in six skulls. Some had just a few bite marks, while others displayed up to 18 perforations clustered around the whales' faces. "It was clear to us something was happening — sharks were somehow predating on these animals and trying to feed on their noses," Benites-Palomino said.

Variations in size and shape of the bite marks suggested that multiple shark species were lining up to take a bite. Large bite marks with a little bit of serration were "typical megalodon," while deep slices that looked like they were made with a sharp knife "could be either mako or sand sharks," he explained. "And then, if you have something in the middle — a little shallower and the serration is irregular — these are mostly caused by members of the white shark lineage."

Modern sharks are known for eating many things (including songbirds, sea turtles and even humpback whale carcasses) but not sperm whales, according to the study. This raises questions about what may have driven these voracious predators to shift their diet away from their once-favorite meal: sperm whales' delicious noses.

"You start to imagine how this changed, why this changed, was there some implication in the environment," Benites-Palomino said. "More than actually answering questions, I think this is making me have more inquiries around all of these discoveries."

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.