Ancient Skeletons with Alien-Like Heads Unearthed in Croatia

Artificial cranial deformation has been practiced in various parts of the world.

Archaeologists have unearthed three ancient skeletons in Croatia — and two of them had pointy, artificially deformed skulls.

Each of those skulls had been melded into a different shape, possibly as a way to show they belonged to a specific cultural group.

Artificial cranial deformation has been practiced in various parts of the world, from Eurasia and Africa to South America. It is the practice of shaping a person's skull — such as through using tight headdresses, bandages or rigid tools — while the skull bones are still malleable in infancy.

Ancient cultures had different reasons for the practice, from indicating social status to creating what they thought was a more beautiful skull. The earliest known instance of this practice occurred 12,000 years ago in ancient China, but it's unclear if the practice spread from there or if it emerged independently in different parts of the world, according to a previous Live Science report.

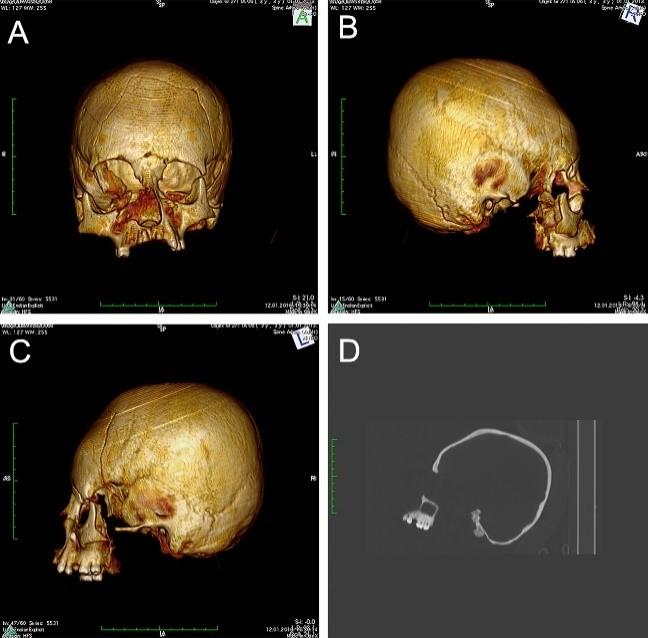

In this case, archeologists found these three skeletons in a burial pit in Croatia's Hermanov vinograd archeological site in 2013. Between 2014 and 2017, they analyzed the skeletons using various methods, including DNA analysis and radiographic imaging— a method that involves using radiation to view the inside of an object such as a skull.

Related: In Images: An Ancient Long-headed Woman Reconstructed

Their analysis revealed that the skeletons were all males who had died between ages 12 and 16. They all showed evidence of malnutrition, but that's not necessarily how they died. They could have had "some kind of disease that killed them quickly and didn't leave any traces on their bones," such as plague, said senior author Mario Novak, a bioarchaeologist at the Institute for Anthropological Research in Zagreb, Croatia.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The archaeologists didn't find artifacts in the burial that could have revealed the boys' social status, Novak said.

Analysis also revealed that the three had lived between A.D. 415 and 560, a time that corresponds to the Great Migration Period, which is "a very turbulent period in Europe's history," Novak told Live Science. Right after the fall of the Roman Empire, completely new populations of people and cultures began to arrive in Europe and become the basis for modern European nations. "In other words, this period set the foundations of Europe as we know it today," Novak said.

Indeed, DNA analysis of the ancient trio revealed that one of them had a West Eurasian ancestry, another a near-Eastern ancestry and the third an East Asian ancestry.

The boy who was of near-Eastern ancestry had a circular-erect type cranial deformation, which means that the frontal bone behind the forehead was flattened and the height of the skull was "significantly increased," Novak said. The boy who likely came from West Eurasia didn't have any skull deformation, and the boy with East Asian ancestry had a skull with an "oblique" deformation, which means the skull was elongated diagonally upward.

"We propose that different skull deformation types in Europe were used as a visual indicator of association with a certain cultural group," Novak said. As of yet, it's unclear what cultural groups they belonged to, though the East Asian boy could have been a Hun.

Now, Novak and his team hope to find more samples of cranial deformation from Europe to understand this phenomenon on a larger scale.

The findings were published yesterday (Aug. 21) in the journal PLOS One.

- In Photos: 'Alien' Skulls Reveal Odd, Ancient Tradition

- In Photos: Amazing Human Ancestor Fossils from Dmanisi

- In Photos: 13-Million-Year-Old Primate Skull Discovered

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.