Walking whale ancestor named after Egyptian god of death

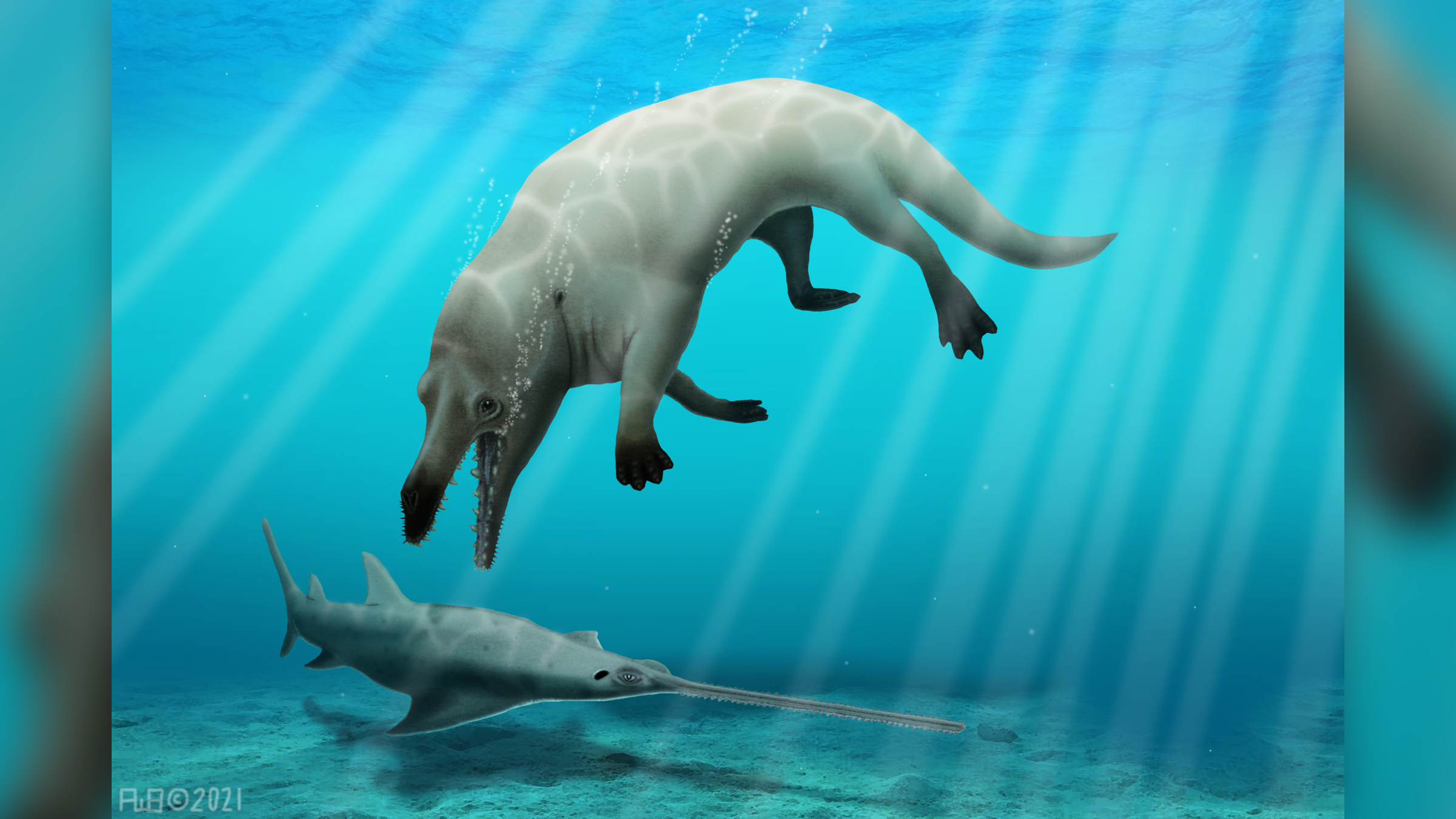

The semiaquatic whale walked on land and swam in water.

A semiaquatic whale that lived 43 million years ago was so fearsome, paleontologists have named it after Anubis, the ancient Egyptian god of death.

The newly discovered 10-foot-long (3 meters) species, dubbed Phiomicetus anubis, was a beast; When it was alive more than 43 million years ago, it both walked on land and swam in the water and had powerful jaw muscles that would have allowed it to easily chomp down on prey, such as crocodiles and small mammals, including the calves of other whale species.

What's more, the whale's skull bears a resemblance to the skull of the jackal-headed Anubis, giving it another link to the death deity, the researchers observed. "It was a successful, active predator," study lead author Abdullah Gohar, a graduate student of vertebrate paleontology at Mansoura University in Egypt, told Live Science. "I think it was the god of death for most animals that lived alongside it."

Related: Photos: Orcas are chowing down on great-white-shark organs

Although today's whales live in the water, their ancestors started out on land and gradually evolved into sea creatures. The earliest known whale, the wolf-size Pakicetus attocki, lived about 50 million years ago in what is now Pakistan. The new discovery of P. anubis sheds more light on whale evolution, said Jonathan Geisler, an associate professor of anatomy at the New York Institute of Technology who was not involved with the study.

"This fossil really starts to give us a sense of when whales moved out of the Indo-Pakistan ocean region and started dispersing across the world," Geisler told Live Science.

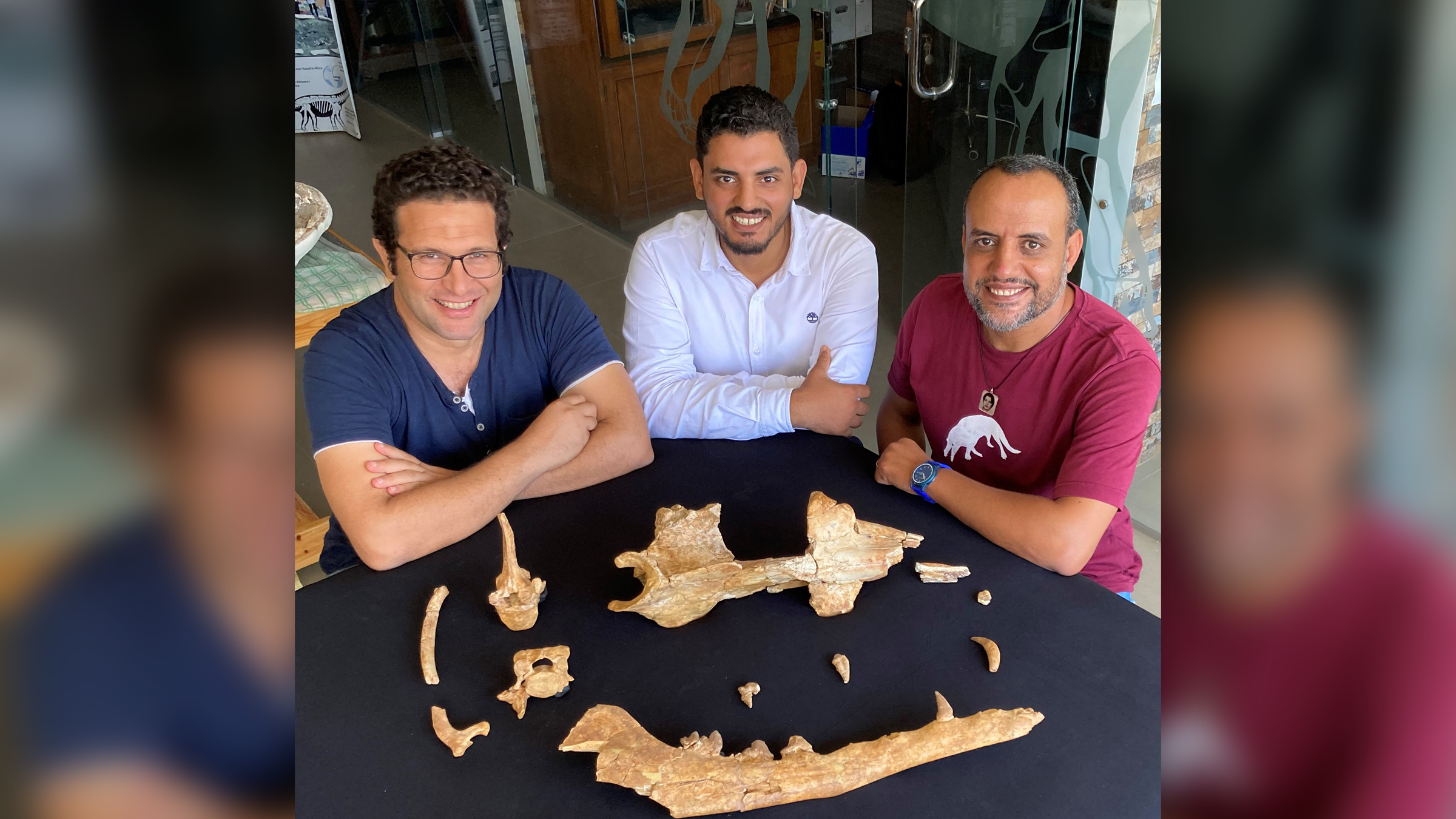

Paleontologists discovered the fossil remains of P. anubis in 2008, during an expedition in Egypt's Fayum Depression — an area famous for sea life fossils, including those of sea cows and whales, dating to the Eocene epoch (56 million to 33.9 million years ago). The expedition was led by study co-researcher Mohamed Sameh Antar, a vertebrate paleontologist with the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency, making this the first time that an Arab team has discovered, scientifically described and named a new species of fossil whale, Gohar said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By analyzing the whale's partial remains — pieces of its skull, jaws, teeth, vertebrae and ribs — the team discovered that the 1,300-pound (600 kilogram) P. anubis is the earliest (or most "primitive") whale in Africa from a group of semiaquatic whales known as the protocetids.

P. anubis's remains revealed that the protocetid whales had evolved a few new anatomical features and feeding strategies. For instance, P. anubis had long third incisors next to its canines, "which suggests that incisors and canines were used to catch, debilitate and retain faster and more elusive prey items (e.g. fish) before they were moved to the cheek teeth to be chewed into smaller pieces and swallowed," the researchers wrote in the study.

Moreover, big muscles on its head would have given it a powerful bite force, allowing it to capture large prey through snapping and biting. "We discovered how [its] fierce, deadly and powerful jaws were capable of tearing a wide range of prey," Gohar said.

P. anubis wasn't the only fossil whale from the middle Eocene of Egypt. Its fossils came from the same area as a previously discovered Rayanistes afer, an early aquatic whale. This finding suggests that the two early whales lived in the same time and place, but likely occupied different niches. It's even possible that P. anubis hunted R. afer calves, making its "Anubis" name all the more appropriate, Gohar said.

Granted, to some animals, P. anubis was prey. The ribs of the newly described whale have bite marks that "suggest it was once bitten severely by sharks," Gohar said. However the marks indicate that the sharks were small, and likely not large enough to kill the whale; rather, these sharks were likely scavenging its carcass.

Gohar and colleagues analyzed the fossils in the lab of Hesham Sallam, founder of the Mansoura University Vertebrate Paleontology Center and the study's senior author. The study was published online Wednesday (Aug. 25) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.