13 of the most venomous sea creatures lurking in the water

From blue-ringed octopuses to stonefish, here are some of the most venomous, deadly species in our planet's oceans.

Earth's oceans are home to some of the most venomous species on Earth, delivering stings and bites that can kill a human in minutes. And venomous marine critters will become more common as climate change enables creatures like box jellyfish and sea snakes to gain a foothold in new regions.

But what are the most venomous species in the sea? Here's a list of some of the deadliest sea creatures on Earth.

Blue-ringed octopuses (Hapalochlaena)

There are four known species of blue-ringed octopus, all of which are highly venomous and can kill a human within just a few minutes. The venom contains a neurotoxin called tetrodotoxin, which is 1,000 times more potent than cyanide — and there is no antivenom available to counteract it. Tetrodotoxin is found throughout the octopuses' tissues, not just in specific venom glands, which makes these creatures among the few animals that are both poisonous and venomous.

Blue-ringed octopuses are found in tropical and subtropical waters of the Indian and Pacific oceans. This species gets its name from its beautiful but fear-inducing rings — the markings only appear when the octopuses feel threatened or are about to dispense their lethal venom.

Bites are often painless, but the venom causes paralysis that can lead to respiratory failure. The effects can occur rapidly or more slowly, so death can occur anywhere between 20 minutes and 24 hours after the toxin enters the body, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Three people are known to have died from blue-ringed octopus bites.

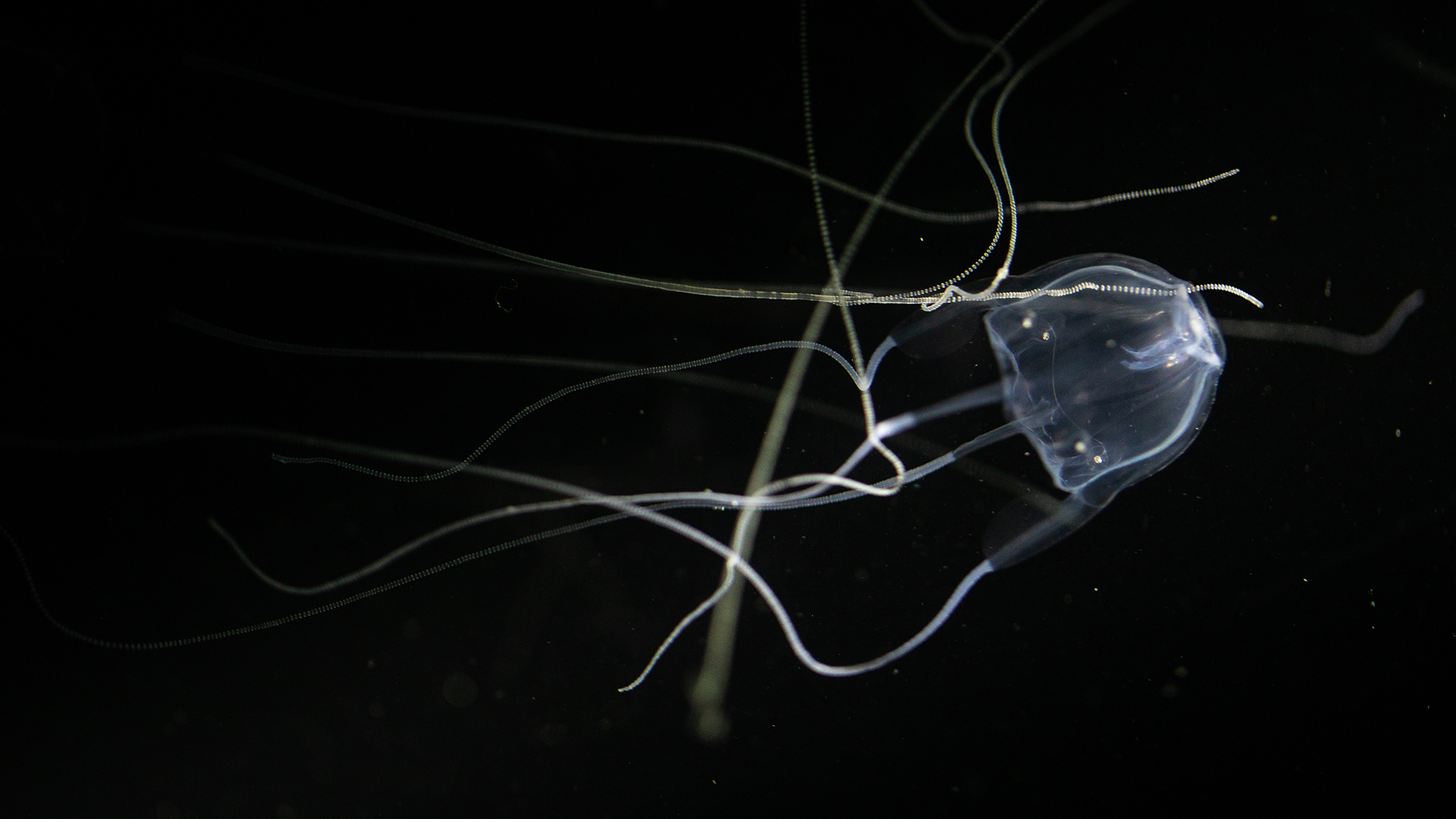

Australian box jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri)

Australian box jellyfish are considered some of the most dangerous animals in the ocean to humans. They live around northern Australia and Southeast Asia. Their tentacles are up to 10 feet (3 meters) long, and they have transparent bells measuring around 12 inches (30 centimeters).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Venom is injected via specialized cells in the tentacles called nematocysts. Their stings are incredibly painful and can cause paralysis and heart failure within minutes if enough venom is injected. They are known to have killed over 70 people in the last century — but the number of fatalities is likely far higher due to a lack of available data.

Irukandji box jellyfish (Carukia barnesi)

Of the 50 or so known box jellyfish species, the Irukandji is one of the most well-known and even has a syndrome named after it — the Irukandji syndrome. The name "Irukandji" comes from the Aboriginal people in the Cairns area of Australia, where the species occurs frequently. The species is very small, growing to only 0.8 inch (2 cm) in diameter and with only four tentacles, but it packs a mighty punch. And it's not only the tentacles that pose a risk — the bell also contains venom-containing nematocysts.

The sting itself is mild, but more serious symptoms can set in between 20 and 40 minutes later. These include severe pain, muscle cramping, high heart rate and blood pressure, fluid in the lungs and potentially life-threatening cardiac complications. There are between 50 and 100 hospitalizations due to Irukandji syndrome in Australia each year.

Twenty five species of box jellyfish can cause Irukandji syndrome, but Carukia barnesi is the one usually associated with it.

Portuguese men o'war (Physalia physalis)

Often mistaken for a jellyfish, the Portuguese man o' War is actually a venomous siphonophore, which is made up of a colony of specialized individuals known as zooids that work together as one unit. A Portuguese man o' war is composed of four different parts, or polyps — bladder, tentacles, digestive and reproduction.

The topmost polyp forms the blue-purple gas-filled bladder that sits above the water and gives the species its name — it is thought to resemble an old warship.

Like jellyfish, Portuguese men o' war also have stinging tentacles that can be about 30 feet (10 m) long and are used to catch and paralyze fish. These tentacles can cause a painful sting when touched by humans, even when a Portuguese man of war is dead. The stings can cause shock and fever. Deaths have been recorded, but cases are extremely rare.

Geography cone snail (Conus geographus)

There are more than 1,000 species of cone snails, which vary in size and have conical-shaped shells. These mollusks are predatory and have venom-filled, harpoon-like modified teeth that they use to paralyze their prey — usually small fish, invertebrates and other cone snails.

Not all cone snails are dangerous to humans, but one species found in the reefs of the Indo-Pacific definitely is. Geography cone snails can grow up to 6 inches (15 cm) long. They are estimated to have more than 10,000 active compounds in their venom, and a sting can cause respiratory paralysis resulting in death. According to a study published in 2016 in the International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, geography cone snails have been responsible for about 15 deaths in the last 30 years.

Stonefish (Synanceia)

Stonefish are a highly venomous group of fish that camouflage themselves among coastal reefs in the Indian and Pacific oceans. Stonefish have dorsal spines containing venom that is released under pressure — such as when someone steps on them. When injected into a human, it causes excruciating pain and swelling.

Dozens of people are stung by stonefish in Australia every year. While most are mild cases requiring a short hospital stay, extreme cases can result in respiratory difficulties, convulsions, heart failure and death. In 2018, an 11-year-old boy died after a stonefish sting led to pulmonary edema.

Red lionfish (Pterois volitans)

With gorgeous red and white stripes, fan-like fins and dorsal spines, red lionfish are a wonder to behold — but at a distance. Those dorsal spines contain venom that can cause nausea, breathing difficulties and paralysis in humans. However, they rarely cause death.

The species is native to the South Pacific and Indian oceans but has become highly invasive in the Caribbean and southeastern U.S. coast. It preys on native fish and has no known predators to keep its population in check. It can also reproduce all year round. It's estimated that a mature female can produce 2 million eggs every year. In Florida, chefs are working with divers to promote eating lionfish as a way to reduce their numbers.

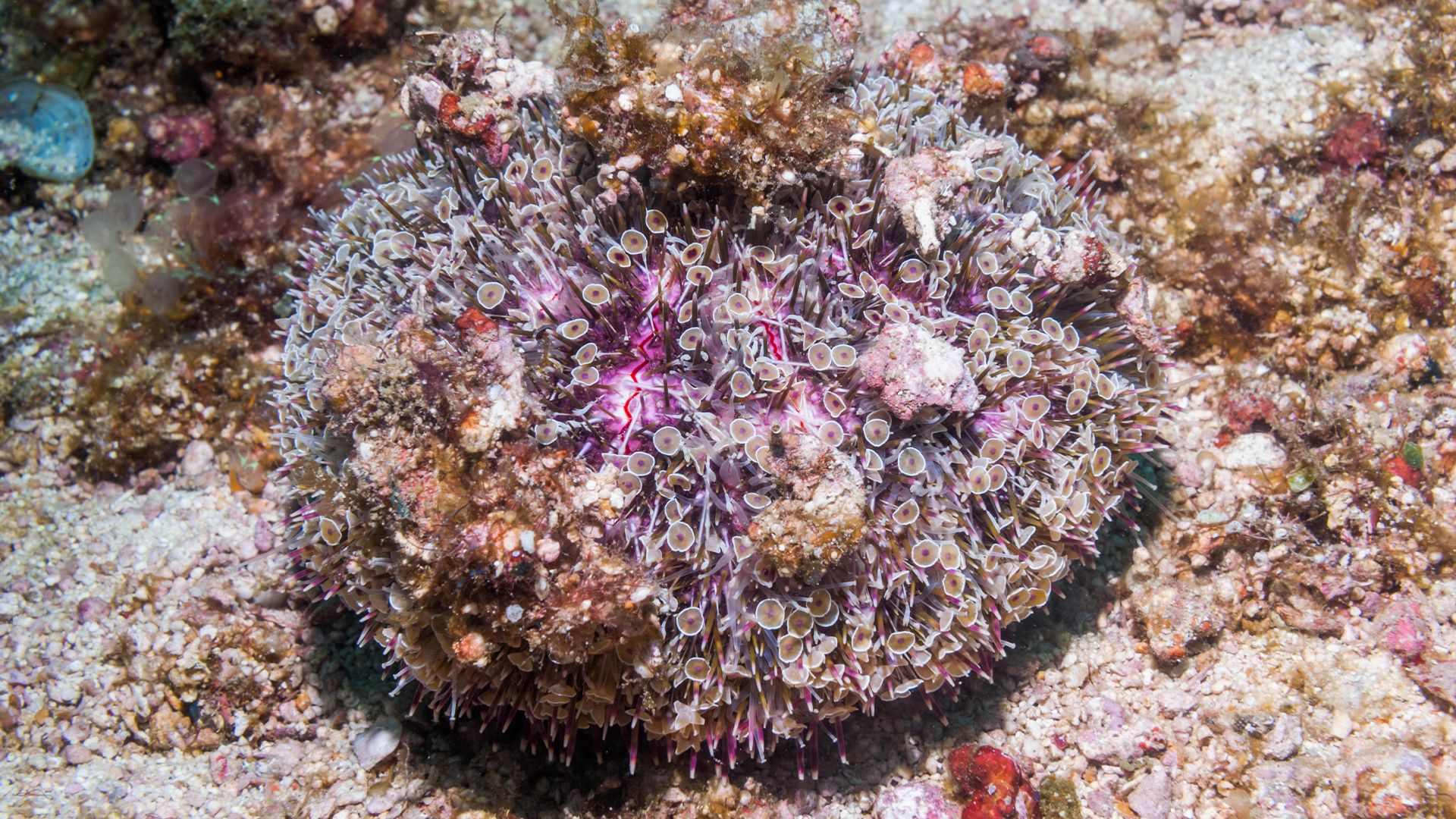

Flower urchin (Toxopneustes pileolus)

Crowned the world’s most dangerous urchin species by Guinness World Records, flower urchins contain venom in their spines and appendages. For humans, this venom is very dangerous: After being stung, symptoms include paralysis, respiratory problems and severe pain.

Flower urchins can grow to be up to 15 inches (28 cm) in diameter and are found in seagrass, coral reefs and rocky or sandy environments of the Indo-West Pacific.

Striped pyjama squid (Sepioloidea lineolata)

These dapper cephalopods double the danger level by being both venomous and poisonous. The venom comes from their bite and contains the neurotoxin tetrodotoxin. These creatures also produce a poisonous slime to deter predators.

Despite the name, they are actually not squids. Instead they are cuttlefish. Found in Australia, they only grow to two inches (5 cm) long and are also known by the alternative name of striped dumpling squids.

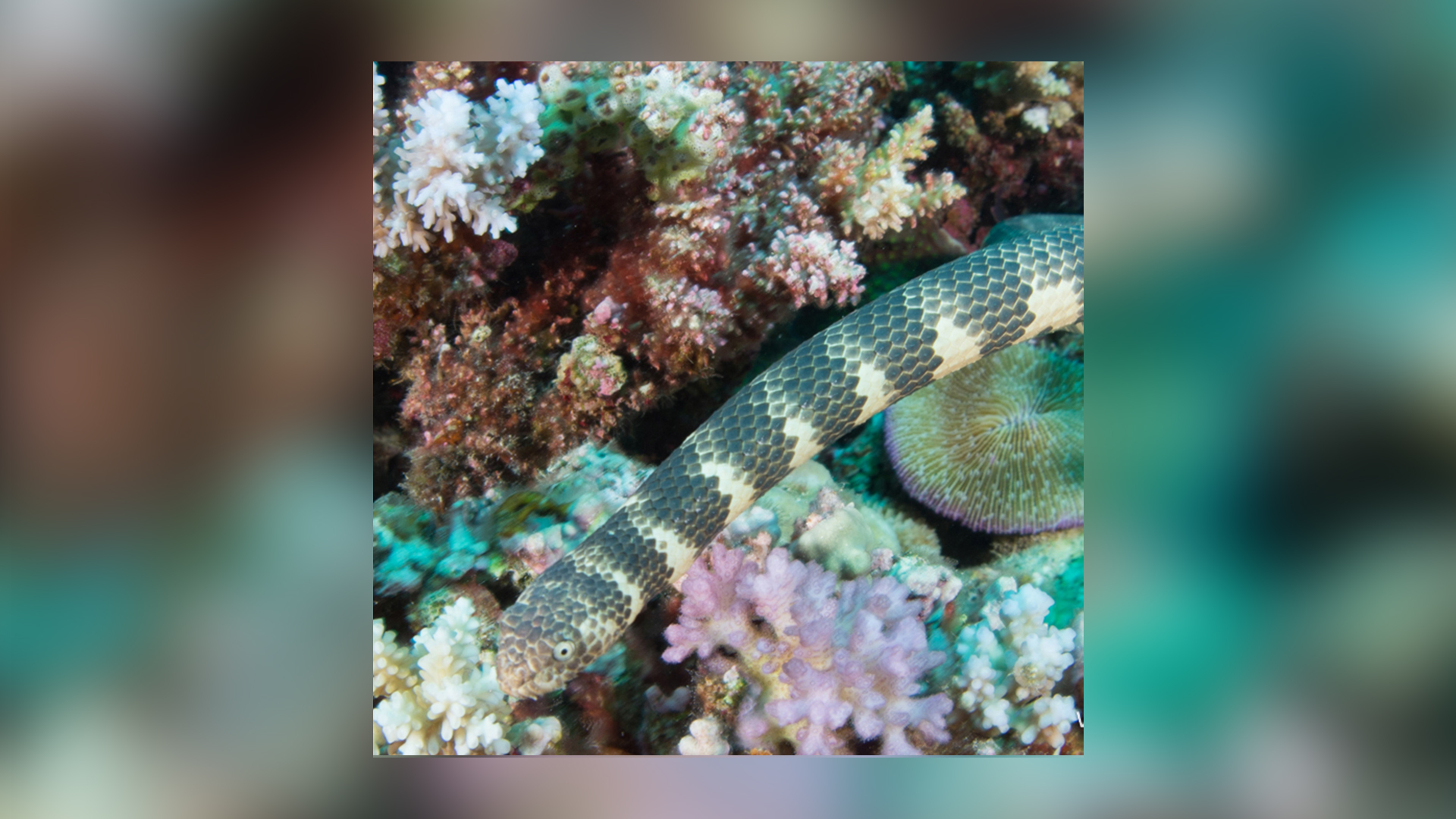

Dubois' sea snake (Aipysurus duboisii)

There are more than 60 species of sea snakes, most of which are venomous. Several of these species are particularly dangerous to humans, such as the Dubois' sea snake, which is found in Australia, Papua New Guinea and New Caledonia. Also known as the reef shallows snake, this species can spend between 30 minutes and two hours underwater hunting for fish. It is the most venomous marine snake in the world and is one of the top three most venomous snakes overall. Its bite is mild because of its tiny fangs, but its venom can cause nausea, vomiting, dizziness, collapse and convulsions.

Beaked sea snake (Enhydrina schistosa)

Venomous beaked sea snakes, also known as hook-nosed sea snakes or Valakadyn sea snakes, grow to an average of 3.9 feet (1.2 m) long and are found in both the sea and freshwater lakes in and near the Indian Ocean.

In a review of sea snake bites in the Malay Peninsula, beaked sea snakes were found to be responsible for half of all bites, with fishers in areas where the species is endemic the most common victims. Their venom is more potent than that of a cobra.

Japanese pufferfish (Takifugu rubripes)

The majority of pufferfish species are toxic, with their skin and organs accumulating tetrodotoxin through bacteria in their diet. The Japanese pufferfish is one of the best-known pufferfish species due to it being commercially farmed for human consumption.

Pufferfish meat is considered a delicacy in Japan, where it is called "fugu." This expensive dish requires incredibly skilled preparation from certified chefs: If incorrectly prepared it can lead to death. Around 50 people die from pufferfish poisoning in Japan every year.

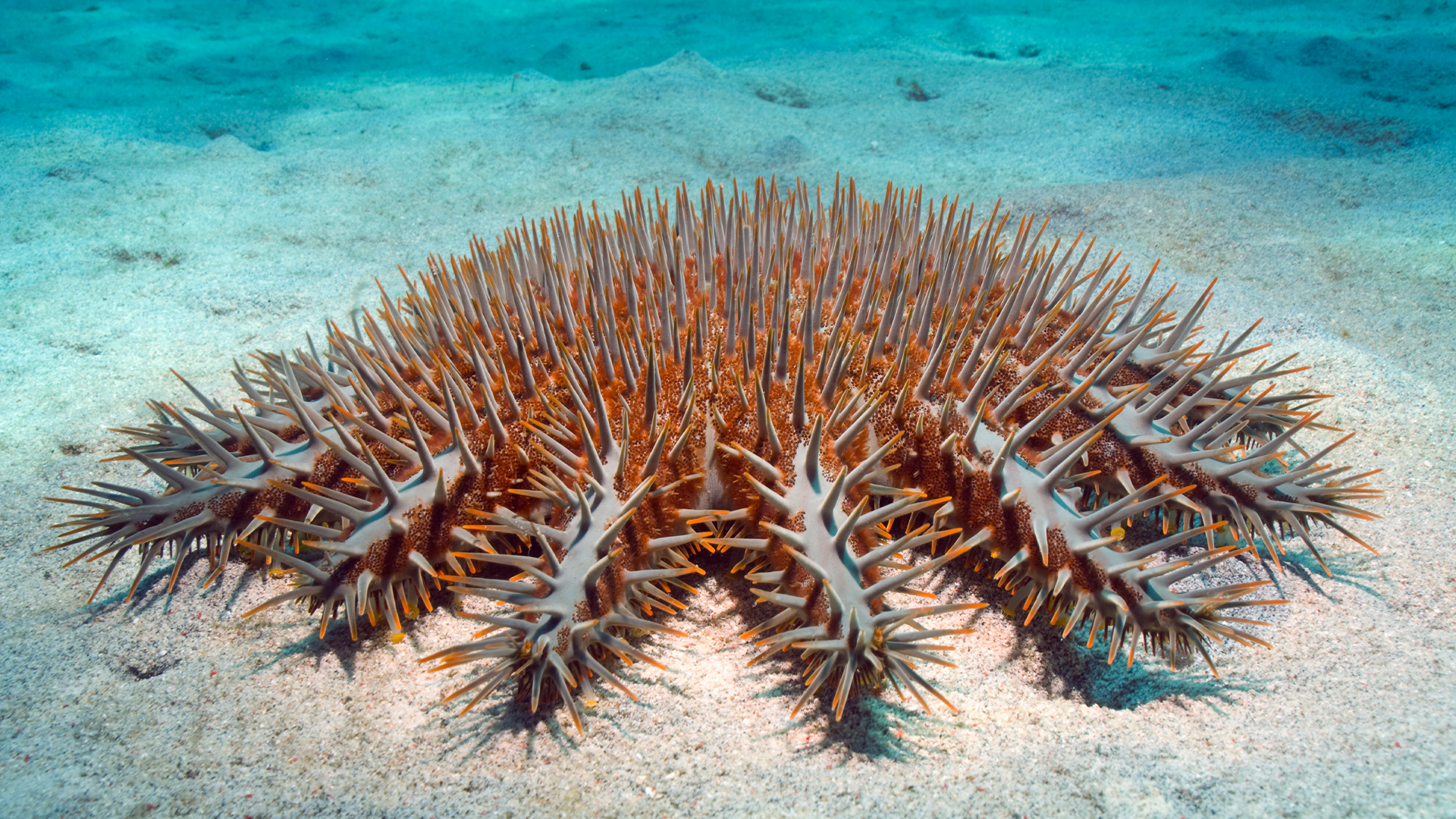

Crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci)

Crown-of-thorns starfish — or COTS for short — are found on reefs in the Indo-Pacific region, including the Great Barrier Reef. They are covered in spikes that contain venomous toxins. They are also enormous, reaching up to 3 feet (1 m) wide. They feed by extruding their stomachs and wrapping them around corals to digest the tissues.

If stung, COTS venom can lead to pain, vomiting, swelling and in rare cases, anaphylactic shock and death.

Megan Shersby is a naturalist, wildlife writer and content creator. After graduating from Aberystwyth University with a BSc (Hons) degree in Animal Science, she has worked in nature communications and the conservation sector for a variety of organisations and charities, including BBC Wildlife magazine, the National Trust, two of the Wildlife Trusts and the Field Studies Council. She has bylines in the Seasons anthologies published by the Wildlife Trusts, Into The Red published by the BTO, and has written for the BBC Countryfile magazine and website, and produced podcast episodes for its award-winning podcast, The Plodcast.