32 of the loudest animals on Earth

Some of the world's animals produce ear-splitting sounds — and some the loudest out there may come as a surprise.

Listening to the sounds of nature is known to make people feel more relaxed, helping reduce stress and anxiety as well as improving mood and productivity. But the calls of some animals are not so peaceful, reaching levels that could cause permanent damage to our hearing.

From the tiniest bugs with ear-piercing shrieks to giants of the ocean that are as loud as jet engines, here are 32 of the loudest animals on Earth.

Blue whales

The blue whale claims the title for not only being the largest animal in the natural world — it is also the loudest. It can emit calls — or long rumbling "songs" that hit 188 decibels — louder than a jet engine and loud enough to damage human eardrums. Blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) are mostly solitary marine mammals, only coming together to mate or migrate. They use their deafening call to communicate in the vast oceans, with their song heard up to 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) away. Scientists have recorded a decline in tonal song by blue whales, but the reason why still remains a mystery.

Sperm whales

Diving to depths of over 10,000 feet (3,050 meters), sperm whales are another whale species that emit loud clicks similar to Morse code to communicate. Using echolocation to hunt for prey such as giant squid, sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) emit short bursts of high-pitched clicks, known as codas, which can reach 230 decibels. Although this noise is louder than the blue whale call, it lasts a fraction of the time. A 2024 study has found evidence that sperm whales communicate using a complex "phonetic alphabet" and could be using different types of vocalizations to communicate.

Bowhead whales

Another marine mammal that uses long, rumbling songs and moans to communicate at volume across Arctic waters is the bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus). With the longest baleen — or filter-feeding system —of all baleen whale species, bowhead whales can reach up to 15 feet (4.6 m) in length.

Their calls can reach up to 159 decibels and their complex vocalizations range from longer moans to shorter calls, which vary in intensity and frequency. A 1987 study found evidence of 20 repeated phrases in songs of bowhead whales off the coast of Alaska, with one phrase lasting up to 146 seconds.

Greater bulldog bats

The loudest species in the bat family Noctilionidae, the greater bulldog bat (Noctilio leporinus) can emit loud "chirps" of up to 140 decibels. Using echolocation to track and hunt for fish in rivers and ponds, it is sometimes known as the "fisherman bat." Although the frequency of its call is too high for the human ear to detect, it has a similar intensity to that of a gunshot. The greater bulldog bat emits this loud noise when it flies to communicate with other bats. It is also the third loudest animal in the world.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Lesser bulldog bats

Around half the size of the greater bulldog bat, another noisy bat is the lesser bulldog bat (Noctilio albiventris), which can emit chirps of up to 137 decibels. Although the frequency is too high for human hearing to detect, it would be deafening at a lower frequency.

Scientists recording bats species in Panama found evidence that the lesser bulldog bat call could be louder still, with bats recorded emitting the highest frequency call traveling further than the lower frequency calls, suggesting that directionality played a role in noise levels.

African cicadas

Cicadas are the loudest insects in the world — particularly when they emerge from the ground en masse to take part in a noisy, mating frenzy. All male cicada species use powerful, drum-like membranes in their bellies, known as tymbals, to emit loud mating calls to attract females. The African cicada (Brevisana brevis) wins the accolade of being the loudest cicada, with its song reaching up to 107 decibels, equivalent to a power mower.

A 2003 study found evidence that African cicadas warm up before calling, suggesting that they rely on muscle power to emit their fierce mating cry.

Synalpheus pinkfloydi

Named after the legendary rock band Pink Floyd by music-loving scientists, Synalpheus pinkfloydi, is a snapping shrimp species that was only discovered in 2017. When this shrimp uses its huge, pink claw to grab and kill small fish prey, it creates a noise that reaches 210 decibels — louder than the average rock concert.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), by quickly closing their large claws, a small, high-pressure bubble is formed which it quickly pops, creating a loud sonic boom. This stuns fish, which it then catches and eats.

Lions

The lion's roar is a distinctive and easily-recognized sound that strikes fear into prey. It's the loudest roar of all big cat species, reaching up to 114 decibels, and can be heard up to 5 miles (8 km) away. Lions (Panthera leo) have a square and flat larynx, which enables air to pass through more easily and roar with ease.

A sociable big cat, male lions in particular roar to signal dominance, while the females use it to scare off intruders. Both sexes roar to communicate with others in the pride.

In a 2020 study, scientists were able to apply a pattern recognition algorithm to identify individuals by their roar with 91.5% accuracy.

Howler monkeys

The world’s loudest primate, howler monkeys can emit a call — or piercing scream — that can reach up to 90 decibels and be heard up to 3 miles (4.8 km) away.

A 2015 study found that the bigger the testicles in male howler monkeys (Alouatta palliata), the softer their voice. Scientists also found that testes size depends on what sort of society they live in. Where there are multiple males in a group, testes tended to be bigger. When the group consists of one male and multiple females, the male had smaller balls but a booming voice.

Mole crickets

Mole crickets are large, noisy insects commonly found in agricultural fields and grasslands in Australia. To amplify their song, the male mole crickets (Gryllotalpa orientalis) create sound chambers, also known as "calling burrows"and emit a loud "churring" sound to attract females, which fly in to find a mate. The females don't sing but are attracted by the serenading vibrations and churring noise, which can reach 26 decibels.

Hippos

A huge, water-loving land mammal, the common hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius) is a noisy and aggressive species native to Africa. The third-largest land mammals after elephants and white rhinos, hippos are very loud animals, with their signature "wheeze honk" and bellowing call heard more than a half-mile (0.8 km) away, Live Science previously reported.

According to the San Diego Zoo, hippos use subsonic vocalizations to communicate, which have been measured at 115 decibels — around the same volume if you were standing 15 feet (4.6 m) from speakers at a rock concert.

A 2022 study found evidence that hippos can recognize friends from foe by carefully listening to the wheeze honk.

Spotted hyenas

Spotted hyenas use a noisy, raucous giggle when they are feeling threatened or in direct conflict over a kill. The spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta) is the noisiest member of the Hyaenidae family and is known for its giggly and "whooping" behavior. According to scientists, the pitch and variability of hyena laughter could be used to indicate social status and age. Younger hyenas were found to have higher-pitch vocalizations compared to older, more dominant females, and each vocalization is unique to the individual.

Tiger pistol shrimps

One of the loudest creatures of the natural world, the tiger pistol shrimp (Alpheus bellulus) can create a noise up to 200 decibels — louder than a gunshot and deafening to the human ear. It uses its huge claw to snap, creating a high-speed water jet bubble, which emits a sonic shockwave and stuns prey. According to the Ocean Conservancy, these bubbles can reach speeds of 60 mph (97 km/h).

According to marine biologists, warmer oceans caused by climate change could increase the volume and number of “snaps” heard, because cold-blooded animals, such as tiger pistol shrimp, increase activity levels as their body temperatures go up.

Water boatmen

Water boatmen, also known as backswimmers, are surprisingly noisy insects commonly found in freshwater rivers and ponds. According to scientists, relative to its tiny body size, the water boatman species Micronecta scholtzi is louder than any other animal, thanks to its "singing penis," with its song reaching up to 99.2 decibels.

Using a process called stridulation, the male water boatman (Corixidae) emits a loud song by rubbing its penis against its abdomen to attract female mates. Although the sound of strumming water boatmen is audible to the human ear, much of the sound is lost when transferring from water to air.

Salmon-crested cockatoos

An intelligent species with distinctive pink plumes, the salmon-crested cockatoo, also known as Moluccan cockatoo, is a noisy bird. Native to eastern Indonesia, it is the loudest member of 21 species of parrots belonging to the family Cacatuidae. Salmon-crested cockatoos (Cacatua moluccensis) emit a squawking noise that can reach up to 129 decibels — as loud as an aircraft taking off.

According to researchers, squawking loudly allows the birds to communicate in dense forest canopies and form social connections.

Northern elephant seals

With a prominent nose that resembles an elephant trunk, the northern elephant seal (Mirounga angustirostris) is a huge marine mammal — and the second largest seal in the world after the southern elephant seal. Dwelling in the coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean, they migrate twice a year to find new feeding and breeding grounds between California and Mexico.

Males emit a loud, powerful guttural vocalization, which can reach 131 decibels, to identify individuals and determine dominance during breeding season. A 2021 study found that females are able to identify their pups' vocalizations just two days after birth.

Southern elephant seals

The world's largest pinniped (seal) species, southern elephant seals weigh around 40%more than northern elephant seals, with adult males weighing around 2,200 to 4,000 kilograms (5,000 to 9,000 lbs) on average. Found in the Antarctic, aggressive male bulls often emit a loud, guttural roar before starting a bloody combat during mating season, when they return from the ocean to land to breed.

Southern elephant seals (Mirounga leonine) amplify their vocalizations by inflating their trunk-like noses with air, enabling them to emit a bellowing sound.

Atlantic spotted dolphins

Mostly found in the warmer waters of the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic dolphins (Stenella frontalis) are known for being acrobatic swimmers that leap out of the water. In a 2014 study, which compared the frequency and volume of whistles between bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) and Atlantic spotted dolphins, researchers recorded the whistles from Atlantic dolphins reaching up to 163 decibels — the same volume as a rifle firing. However, the Atlantic spotted dolphin whistle duration lasted longer.

A separate 2018 study found that the dolphins used biphonation, when two sounds are produced simultaneously, in its vocalizations to communicate.

Bottlenose dolphins

Bottlenose dolphins, like Atlantic spotted dolphins, can also produce a loud whistle that measures up to 163 decibels from 1 meter (3 ft) away. Highly intelligent and sociable, bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) make two sounds to communicate — loud whistles and clicks.

The dolphins use clicking for echolocation to navigate, search for prey and communicate within their pod in the ocean. In a 2021 study, researchers found that bottlenose dolphins can use vocal signals to communicate and work together collaboratively to hunt. While a 2022 study found evidence of more whistles in group foraging dolphins than solo foragers.

Screaming pihas

Despite its small size, screaming pihas (Lipaugus vociferans emit a loud and piercing call thatcan reach 116 decibels, making it the second loudest bird on record. This aptly-named wild gray songbird is found in tropical forests and rainforests in the Amazon and parts of northern South America.

White bellbirds

White bellbirds (Procnias albus) take the top spot as the loudest wild bird in the world, with researchers finding evidence that they can emit a call up to 125 decibels. The study found that male white bellbirds are the louder sex, emitting deafening vocal signals at a close range with the aim of attracting a female mate.

In a statement, study co-author and professor of biology at the University of Massachusetts Jeffrey Podos said: "We saw that the males sing only their loudest songs. Not only that, they swivel dramatically during these songs, so as to blast the song's final note directly at the females."

Common coquí

Considered to be the loudest frog in the world, male common coquí (Eleutherodactylus coqui) emit loud mating calls at night, which can reach up to 90 decibels. The first part of the call "co" is used to deter competing males, while the second part "kee" is to attract females. According to a 2014 study, a rise in temperature caused by climate change could be causing the chirps produced by the male frogs to become higher pitched and shorter. A 2024 study found evidence to show coquí that adjust their behavior to the environment were more likely to survive in a non-native habitat.

Coquí are an invasive species in Hawaii, where they are so loud they are considered noise pollution. Numbers have reached up to 55,000 frogs per hectare and there are no natural predators to keep them under control.

Roosters

The crow of a cockerel or rooster (Gallus gallus domesticus) can reach 142 decibels, according to a 2018 study. Scientists found that the rooster's eardrum is protected by a flap of soft tissue, which acts as a natural ear protector so it doesn't deafen itself.

Although commonly associated with their early morning crow, which begins at sunrise, cockerels crow throughout the day to communicate with their flock, assert dominance and warn off predators.

Gray wolves

The distinctive howl of a wolf (Canis lupus) can often be heard up to 10 miles (16 km) away. Their howl is used to communicate with the pack and warn off potential intruders to their territory. Using a computer algorithm to determine howl type and frequency, scientists identified 21 different howl vocalizations, enabling them to identify the howl of the three main wolf species and some of the approximately 40 wolf subspecies.

A 2013 study found that wolves howl most frequently to individuals in their pack that they have a close social connection with, rather than strangers. When wolves howl together in a chorus, scientists found evidence of six types of complex vocalizations used among the pack.

Kakapos

A large, flightless bird native to New Zealand, the kakapo — also known as the owl or night parrot — is a critically endangered species, despite conservation efforts.

Both the male and female kakapo (Strigops habroptilus) use loud high-pitched vocalizations known as a skraak calls to communicate.Males make a deep honking or booming call similar to a foghorn to attract a mate to their "lek," a type of bowl-shaped communal area created by the males, which helps amplify their calls.

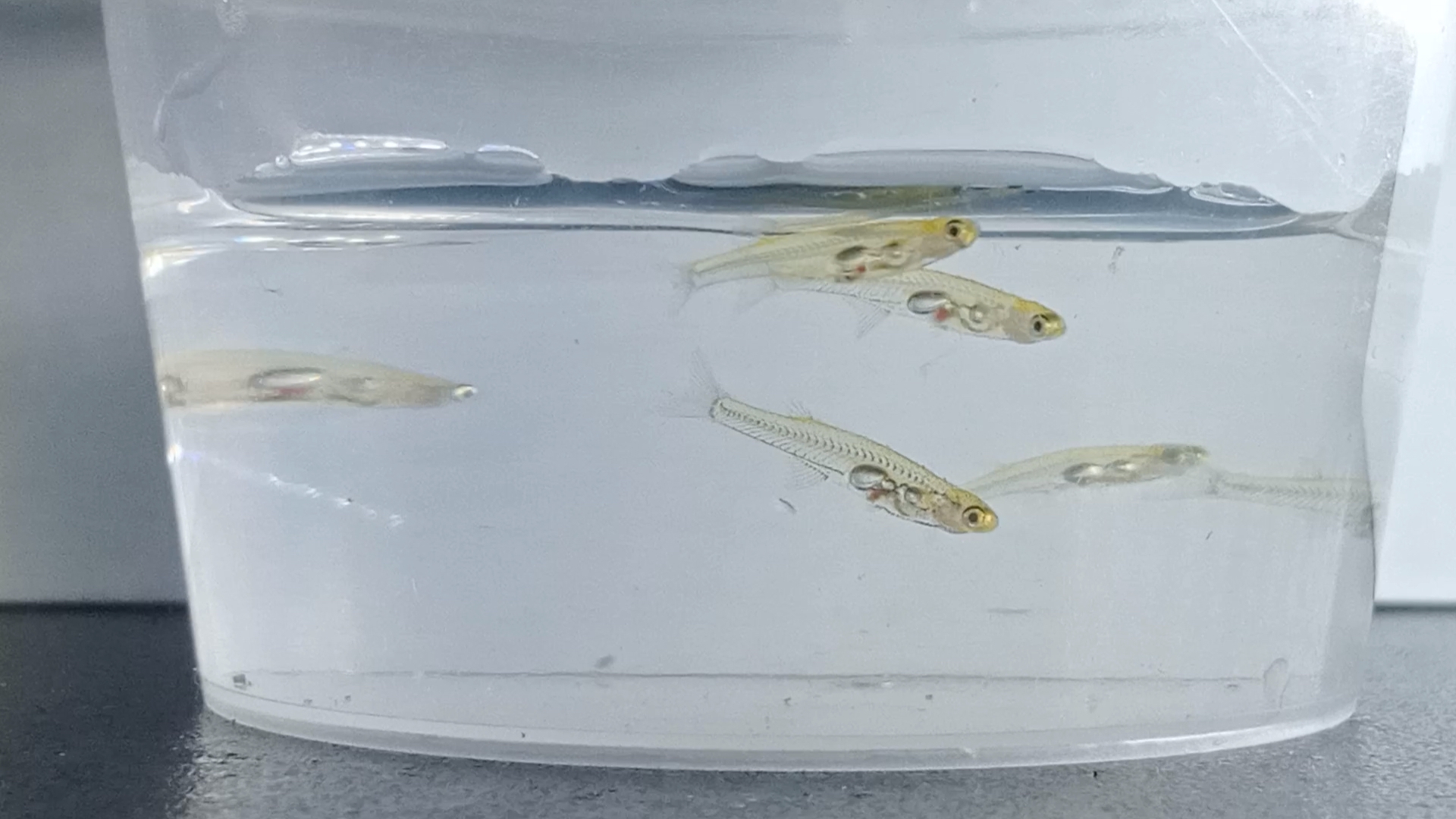

Danionella cerebrum

Only described in 2021, Danionella cerebrum is a tiny cyprinid fish species that emits a clicking sound that can exceed 140 decibels. Measuring just 12 millimeters (0.5 inches), it is the loudest fish relative to its body size ever recorded.

According to a 2024 study, the fish has a complex sound production system, which enables it to make a sound equivalent to a jet engine. It does this using a swim bladder, a gas-filled organ, which it uses to beat a powerful rhythm by using a strong muscle, its ribcage and a cone-shaped cartilage that acts as a drumstick. Why it emits such a loud noise is a mystery.

Chacma baboons

Chacma baboons are highly sociable large primates described as having dog-like snouts and large canines. Found mostly in southern Africa, chacma baboons (Papio ursinus) use over 30 vocalizations to communicate. Their booming barks reach up to 90 decibels. Adult males have been found to begin calling later in life than females.

Researchers have found that females are more likely to grunt quietly.Dominant males give a loud double bark to assert authority, while both sexes emit screeching, clicking and chattering noises of varying volume, according to the Primate Conservancy.

Oilbirds

A small, nocturnal fruit-eating bird found in South America, the oilbird (Steatornis caripensis) can emit up to 100 decibels with its acoustic clicks and calls echoing around its cave habitat. Emitting loud clicks, it uses echolocation to navigate the pitch-black cave system. A 2017 study found that oilbirds' echolocation signals are beyond their best hearing range.

Unlike bats which also use echolocation to navigate and are too high-frequency for humans to detect, the call of the oilbird can be clearly heard by the human ear — particularly when thousands of oilbirds roost together.

Common ostriches

A large, flightless bird known for its incredible running ability, the common ostrich (Struthio camelus) uses a variety of loud vocalizations to communicate, including snorts and guttural sounds.

Found in parts of southern, eastern and northern Africa, male ostriches can emit a loud booming noise by inflating their necks up to three times the original size to create a powerful noise that can reach up to 114 decibels.

According to research published in 2016, ostriches' closed-mouthed mating vocalizations may be similar to how dinosaurs sounded. "To make any kind of sense of what nonavian dinosaurs sounded like, we need to understand how living birds vocalize," study co-author Julia Clarke, geobiologist at The University of Texas at Austin, said in a statement. "This makes for a very different Jurassic world. Not only were dinosaurs feathered, but they may have had bulging necks and made booming, closed-mouth sounds."

African elephants

The largest land mammals in the world, African elephants (Loxodonta africana) use their enormous trunks to breathe, drink, eat, lift small objects and even convey affection. They also use it to trumpet at volume to communicate with others in the herd and warn against intruders.

Measuring up to 7 feet (2.1 m) in length, the elephant's trunk can weigh up to 140 kg (310 lbs) and has around 40,000 muscles, making it a powerful instrument that can trumpet at volumes of up to 117 decibels, researchers from Cornell University’s Elephant Listening Project found. African elephants most commonly "rumble" and scientists found in 2005 that the variation in rumbles reflect the individual identity and emotional state of the elephant. A 2021 study also found that African elephants display vocal creativity and the ability to learn and imitate new sounds.

American bullfrog

A large frog thatdwells in freshwater ponds and rivers, the American bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) makes a loud “mooing” vocalization like a cow or bull and can commonly reach a volume of 110 decibels. Native to North America, it is a non-native species in the U.K. that poses a threat to native frog species.

According to a 2012 study into amphibians and how they perceive sound, frogs produce loud vocalizations to attract females and protect mating sites against rival males. During breeding season, male bullfrogs form a loud chorus to signal their eagerness to mate.

Indian Peafowl

A bird known for its flamboyant appearance, the Indian peafowl, also known as the common peacock, makes loud mewing-like sounds to communicate with and entice a potential partner during mating season.

A 2013 study found that in addition to "singing," male Indian peafowl (Pavo cristatus) loudly call before mating to attract distant female peacocks. The males continued calling during and after mating to warn off potential love rivals.

In many residential areas, peacocks can pose a noise problem, with many local authorities and councils receiving complaints during mating season.

Carys Matthews is a freelance writer for Live Science and has a passion for the natural world. Most recently the group digital editor of BBC Wildlife and BBC Countryfile Magazine, she writes about the outdoors, nature and health and fitness. Prior to this she has worked for a number of sports and environmental titles in the U.K.