Science news this week: The many faces of cats and an impending solar maximum

Nov. 5, 2023: Our weekly roundup of the latest science in the news, as well as a few fascinating articles to keep you entertained over the weekend.

This week in science news, we find out what your cat's face might be telling you, gear up for an impending solar maximum and discover the gruesome answer to the "mermaid" mummy mystery.

Cats, mysterious creatures that they are, always seem to be up to something, but we're never completely sure what's going on in those feline brains. Scientists' curiosity into what cats might be thinking led to a study of the felines in cat cafes, which revealed they have nearly 300 different facial expressions — but can they recognize themselves in the mirror?

Even more astounding animal discoveries this week took us further back in time, to 100,000-year-old mammoth bones in a Russian river, a mosasaur with "angry eyebrows" that lived 80 million years ago, and flesh-eating 'killer' lampreys that lived 160 million years ago in what is now China.

Closer to our own epoch, no doubt the art world will be "rocked" by the news of ancient petroglyphs rising from the drought-stricken Amazon River, or 500-year-old cave art discovered in Puerto Rico.

In space news this week, we found out about protoplanets, a massive solar eruption and an 'impossible' aurora. There was also a frank admission that scientists got their solar cycle predictions wrong, and that we are fast approaching the sun's explosive peak. What does that look like? Well we won't have to wait long for the solar maximum to find out.

In health news, an RSV drug shortage prompted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to adjust recommendations, while scientists learned that a person's epigenetic "clock" may reveal how much a person's memory function has declined over time. Researchers also predicted the effectiveness of Chinese medicine and claimed to have discovered CBD in a plant that's not cannabis.

And finally, a mysterious, malevolent-looking "mermaid" mummy from Japan has been perplexing scientists for more than 100 years. Now we have an idea of what it is — a gruesome Frankenstein's monster of fish, monkey and lizard parts.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Follow Live Science on social media

Want more science news? Follow our Live Science WhatsApp Channel for the latest discoveries as they happen. It's the best way to get our expert reporting on the go, but if you don't use WhatsApp we're also on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), Flipboard, Instagram, TikTok and LinkedIn.

Picture of the week

The skeletal and heart muscle cells of mammals are made up of building blocks known as sarcomeres. These contain thick and thin filaments, called myosin and actin respectively, that interact and enable the muscle to contract. This stunning, multicolored image is the clearest picture to date of what the thick filaments in mammalian heart tissue look like.

The image was taken using a cutting-edge technique known as cryo-electron tomography, or cryo-ET, which helps scientists to paint a clearer picture of the appearance of large molecules within living cells. The team behind it, from the Max Planck Institute (MPI) of Molecular Physiology in Germany, says that it is the world's first true-to-life 3D image of the thick filament in mammalian heart tissue, and that a better understanding of how muscles work could accelerate the development of new therapies to treat heart and muscle disorders.

"Our aim is to paint a complete picture of the sarcomere one day," Stefan Raunser, a director of structural biochemistry at the MPI of Molecular Physiology, said in a statement. "The image of the thick filament in this study is 'only' a snapshot in the relaxed state of the muscle. To fully understand how the sarcomere functions and how it is regulated, we want to analyze it in different states e.g. during contraction," he said.

Sunday reading

- Get your eyes on the skies for the Taurid meteor shower this week.

- When is a dragon not a dragon? When it's an earless monitor lizard, of course.

- Ever wonder why you have a four-pack when others sport six- or even eight-packs?

- These six images show the moment when parasites burst from their hosts — and they're scary.

- Speaking of scary things, this astronaut's photo looks like a skull in a volcano.

- Dentists recommend brushing your teeth twice a day, here's why.

- We know trees are green, but why is the sky blue?

- Watch this monstrous "sea devil" goosefish walk along the bottom of the ocean.

- From bats to hornbills, here are some animals that have historically been associated with death.

Live Science long read

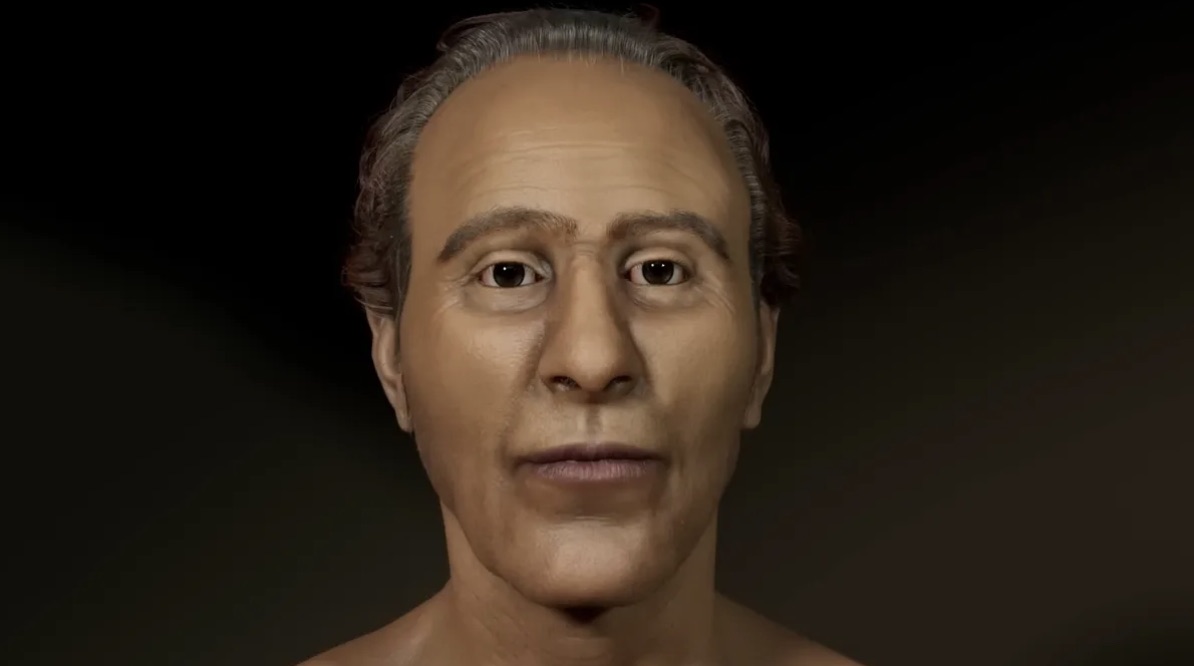

This man was Ramesses II, one of ancient Egypt's most powerful pharaohs. The 19th-dynasty king ruled for 66 years, beginning in 1279 B.C., and his likeness has been chiseled into colossal statues and printed in textbooks around the world. But until recently, only those who met the man knew what he really looked like.

But earlier this year, researchers digitally reconstructed the iconic king's face using a computed tomography (CT) scan of the pharaoh's mummified skull. The final image brought the long-dead ruler back to life.

For decades, researchers have created facial approximations of people from the past, from iconic historical figures like King Tut and English king Henry VII to ordinary individuals lost to time, such as an Incan "ice maiden," an unnamed Stone Age woman and a Neanderthal man.

But how well do these approximations capture what the people looked like in life? And is there any way to measure their accuracy?

Alexander McNamara is the Editor-in-Chief at Live Science, and has more than 15 years’ experience in publishing at digital titles. Before Live Science, he had editor roles at New Scientist and BBC Science Focus.

- Emily CookeStaff Writer