Why do cats make a weird face after smelling something?

"Stink face" seems silly to us, but for cats it's a serious way to gather social information through smell.

When a cat sniffs something, it sometimes adopts a strange facial expression, seemingly shocked by the smell of a stinky object.

So why do cats really make this weird "stink face?" Turns out it has nothing to do with unpleasant odors — it's actually a sign that they're analyzing chemical signals in their environment.

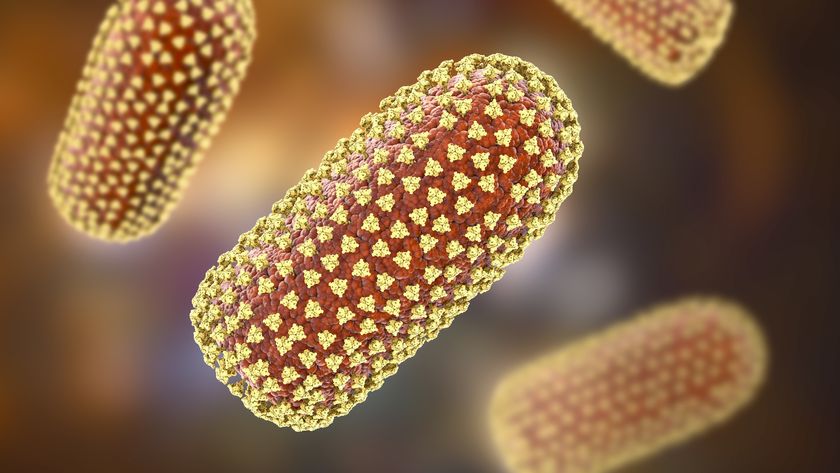

Many animals, including wild and domestic cats, release pheromones — chemical signals used for communication between members of the same species. To detect and decipher these invisible messages, our feline friends rely on a special sensory organ in the roof of their mouths called the vomeronasal organ or "Jacobson's organ."

This organ is separate from the olfactory system (i.e. the nose), which detects odors but not pheromones, Alex Taylor, cat wellbeing and behavior advisor at International Cat Care, told Live Science in an email.

When a cat encounters pheromones, it processes them differently from odors. The cat instinctively opens its mouth slightly, lips curled back, displaying a behavior called the "Flehmen response." This expression makes it easier for pheromone molecules to reach the vomeronasal organ, enhancing the cat's ability to sense important chemical cues.

"This can look like the cat is grimacing, but there is no emotional aspect to this behaviour – the cat is just detecting and processing pheromones," Taylor said.

Related: Why do cats 'chatter'?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cats use pheromones to communicate various messages: they can use them to mark territory without engaging in fighting or to strengthen the bond between mothers and kittens, Taylor explained. Pheromones also convey information about sexual status, indicating when a cat is in heat, said Mikel Delgado, a senior research scientist at Purdue University Veterinary College of Medicine in Indiana.

Pheromones are secreted by specialized glands located in multiple areas around a cat's body, including the chin, cheeks, the space between eyes and ears, edges of the lips, base of the tail, around the genitals and anus, between the paws and between the teats, Taylor said.

When cats rub their faces on furniture, scratch surfaces, spray urine or defecate, they leave behind chemical messages for other cats, Delgado told Live Science in an email. Later, other cats use their vomeronasal organ to analyze these scent marks and gather information about their feline neighbors.

During the Flehmen response, pheromone molecules enter a cat's mouth — either through licking or inhalation — and dissolve in saliva. They then travel through two passages in the roof of the mouth, known as the nasopalatine ducts, which lead to the pair of fluid-filled sacs that make up the vomeronasal organ, Taylor said.

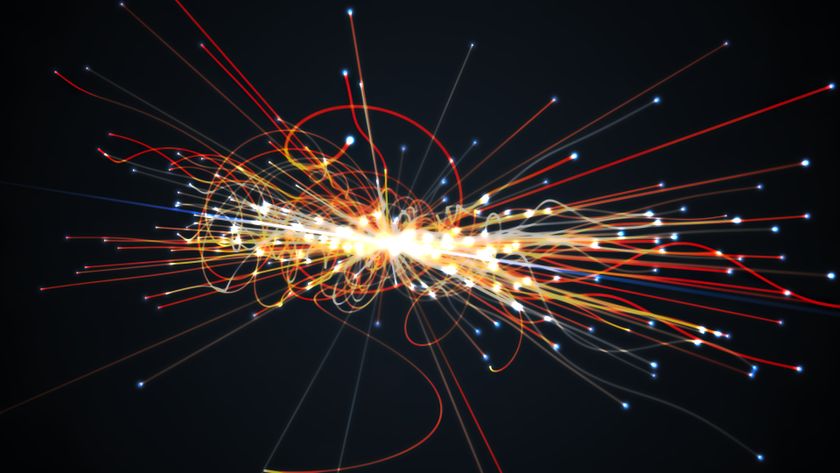

When pheromone molecules reach the vomeronasal organ, they trigger nerve signals that travel to specific areas of the brain, namely the amygdala region of the hypothalamus and a region that controls sexual, feeding and social behaviors, Taylor said. In this way, chemical cues picked up by the vomeronasal organ directly influence a cat's behavior.

Unlike odors, the meaning of which is learned and can change with new experiences, pheromones trigger instinctive responses. A cat doesn't need to "learn" what a pheromone means — the knowledge is hardwired into its biology, Taylor said. While responses to pheromones are automatic, they can still be influenced by factors such as a cat’s development, surroundings, past experiences, and internal state like hormone levels, according to a review published in the Journal of Comparative Physiology A.

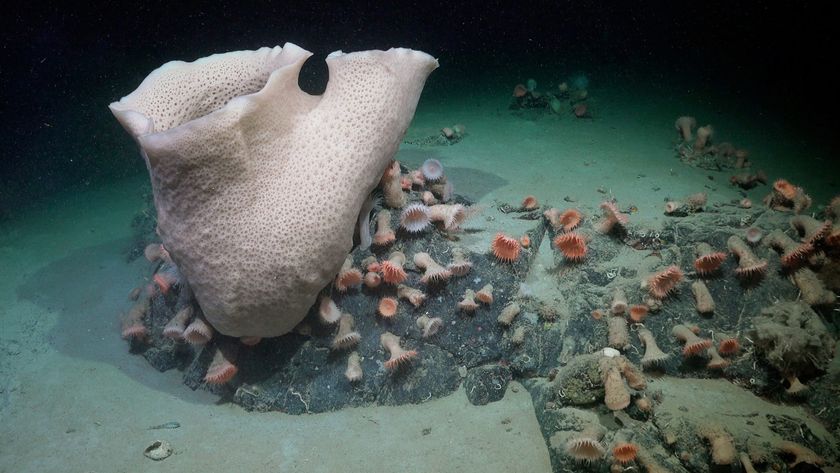

The vomeronasal organ isn't unique to cats. A range of animals, everything from rodents to reptiles, also use this second sense of smell to detect pheromones.

"The advantage of the Jacobson's organ is that animals can detect a wider range of molecules in the environment than animals lacking that organ," Jonathan Losos, an evolutionary biologist at Washington University in St. Louis, told Live Science in an email.

"Dogs are famous for their keen sense of smell, but that refers to their capabilities in their nasal passage," Losos said. "Cats have three times as many different types of scent detectors in the Jacobson's organ as dogs, which leads some experts to suggest that, overall, cat sense of smell may be comparable to that of dogs."

An evolutionary remnant of the vomeronasal organ, is even found in humans within the nasal septum, but there's no strong evidence that this vestigial version plays a role in chemical communication today.

For cats however, the vomeronasal organ is a powerful tool that enables them to interpret important social information in their environment. To quote Scottish novelist and poet Sir Walter Scott: "Cats are a mysterious kind of folk. There is more passing in their minds than we are aware of."

Clarissa Brincat is a freelance writer specializing in health and medical research. After completing an MSc in chemistry, she realized she would rather write about science than do it. She learned how to edit scientific papers in a stint as a chemistry copyeditor, before moving on to a medical writer role at a healthcare company. Writing for doctors and experts has its rewards, but Clarissa wanted to communicate with a wider audience, which naturally led her to freelance health and science writing. Her work has also appeared in Medscape, HealthCentral and Medical News Today.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.