This transparent sea creature can age in reverse

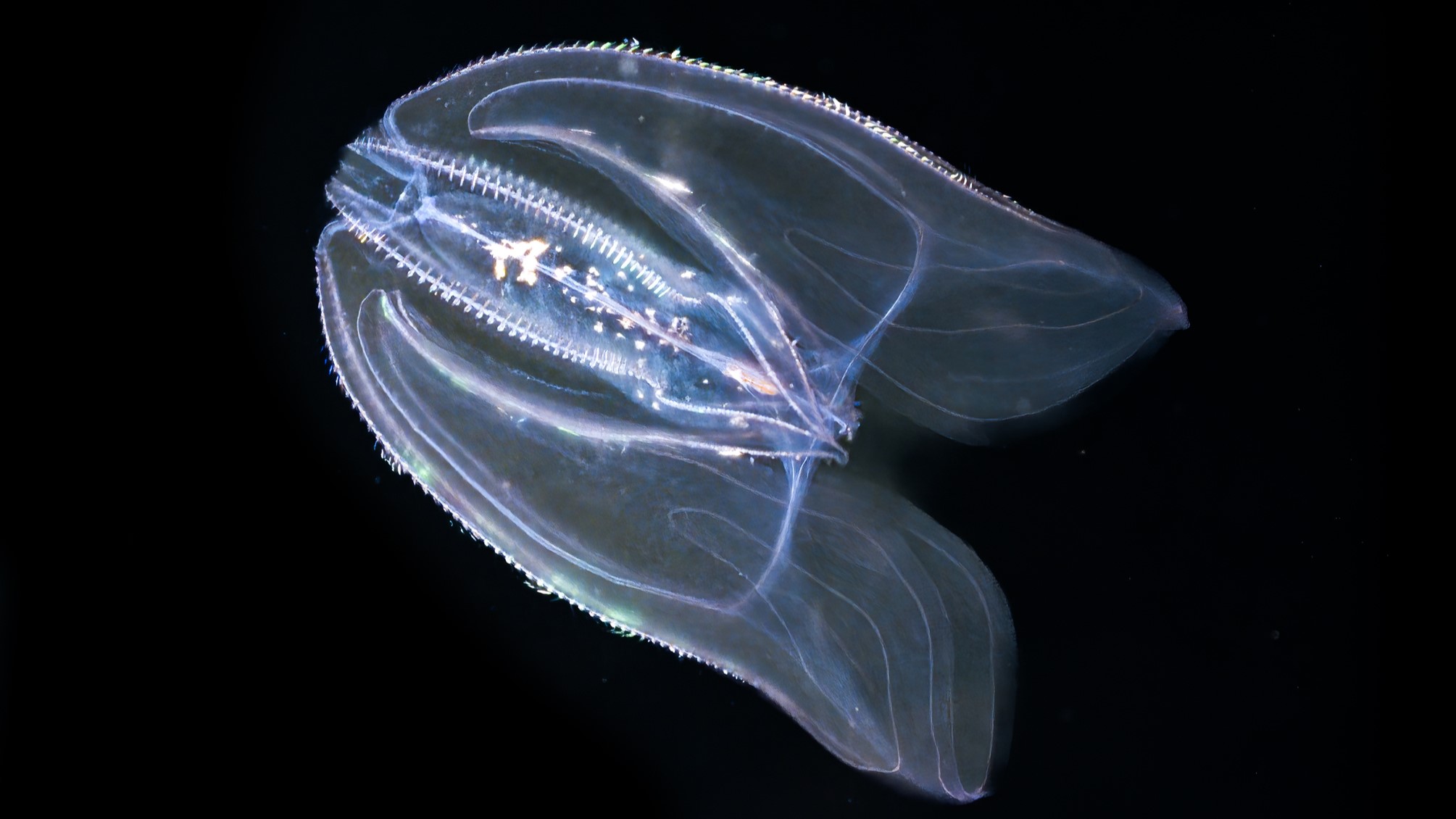

The sea walnut, a type of comb jelly that has become invasive in parts of Europe and Asia, can transform from a sexually mature adult back into its larval form when times are tough.

An Atlantic comb jelly known as the "sea walnut" has the ability to reverse its own aging process, a new study suggests.

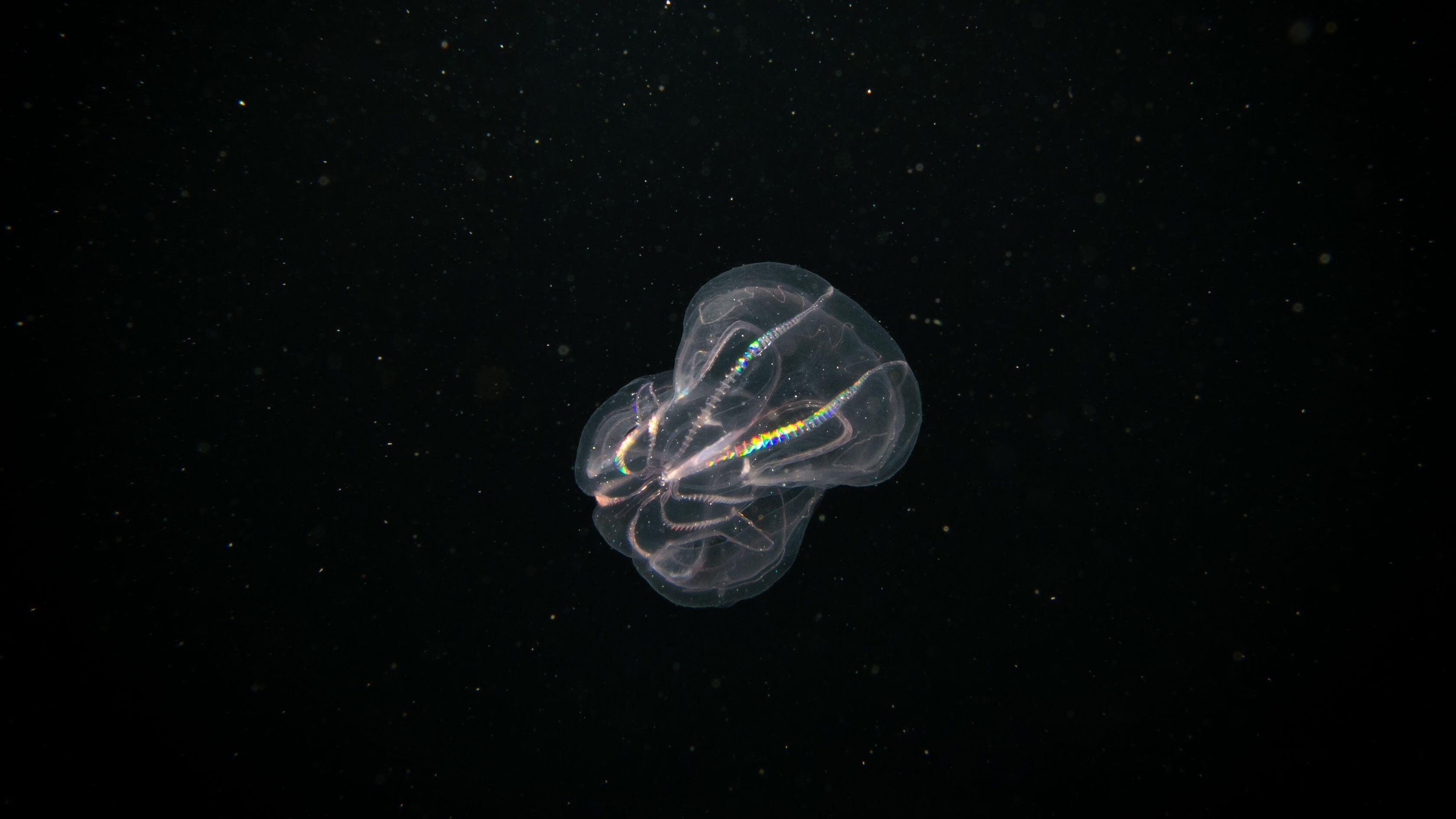

When food is scarce or the sea creature is injured, the gelatinous invertebrate can develop backward into its larval form, which has two tentacles to catch food. The adult form, which looks like a small pair of transparent lungs, lacks these tentacles.

The sea walnut (Mnemiopsis leidyi) is the third-known animal species, and the first-known comb jelly (Ctenophora), that can revert to an earlier life stage after already reaching adulthood, according to the study, which was published Aug. 10 on the preprint database BioRxiv. (It has not yet been peer-reviewed).

Scientists previously showed that a handful of cnidarians — a group that includes jellyfish, sea anemones and corals — can develop backward, but only before reaching sexual maturity. The two other documented species that can develop backward as adults are the so-called immortal jellyfish (Turritopsis dohrnii) and the dog tapeworm (Echinococcus granulosus).

Age reversal in comb jellies "confirms that reversal development might be more widespread than previously thought," researchers wrote in the study, which builds on previous work investigating the sea walnut's hardiness.

Related: Extreme longevity: The secret to living longer may be hiding with nuns... and jellyfish

The sea walnut is native to the western Atlantic Ocean, but the species has spread to become an invasive nuisance in Europe and Asia. M. leidyi can survive in the ballast water of ships for weeks despite the lack of food, which is how researchers think the comb jellies made it across the Atlantic. The species is now found in the Black and Caspian seas, where it has contributed to the collapse of fisheries by competing with native creatures for food, as well as in the Mediterranean, Baltic and North seas.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To shed light on the sea walnut's survival tactics, the researchers carried out experiments in which they starved one group of comb jellies and physically injured another by removing tissue from their lobes. (Like other ctenophores, sea walnuts can regenerate entirely from even a small chunk of flesh. The same researchers previously found that the sea walnut's nervous system is fused, which may confer some advantage for tissue repair and healing.)

Starved and amputated sea walnuts shrunk into tiny blobs, but they didn't die. When the researchers fed both groups again, they observed that 13 out of the 65 comb jellies tested had grown tentacles, a sign they had regressed to the larval stage.

Co-author Joan J. Soto-Angel, a marine biologist and postdoctoral fellow at the University of Bergen in Norway, told Science that the jellies used their tentacles to capture food to which they would not have had access as adults, tapping into a new ecological niche. With enough food, the comb jellies eventually reached their original size again and regrew their lobes. The creatures even regained their ability to reproduce, according to the study.

Finding a third animal capable of aging in reverse "was quite a surprise," Soto-Angel said. The process by which M. leidyi regresses to its larval form is different from how the immortal jellyfish does it, he said, but both animals could help researchers understand aging better.

Comb jellies are also one of the oldest extant animal lineages and possibly the sister group to all animals, making them a unique model to study evolution.

It remains unclear whether the comb jellies really turned back the clock on their age, or whether they simply shrunk, Yoshinori Hasegawa, a zoologist at the Kazusa DNA Research Institute in Japan who was not involved in the research, told Science. “It looks like an imperfect rejuvenation,” Hasegawa said.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.