'If it weren't for that asteroid, they might still share this planet': Dinosaurs weren't doomed before the asteroid hit, new study suggests

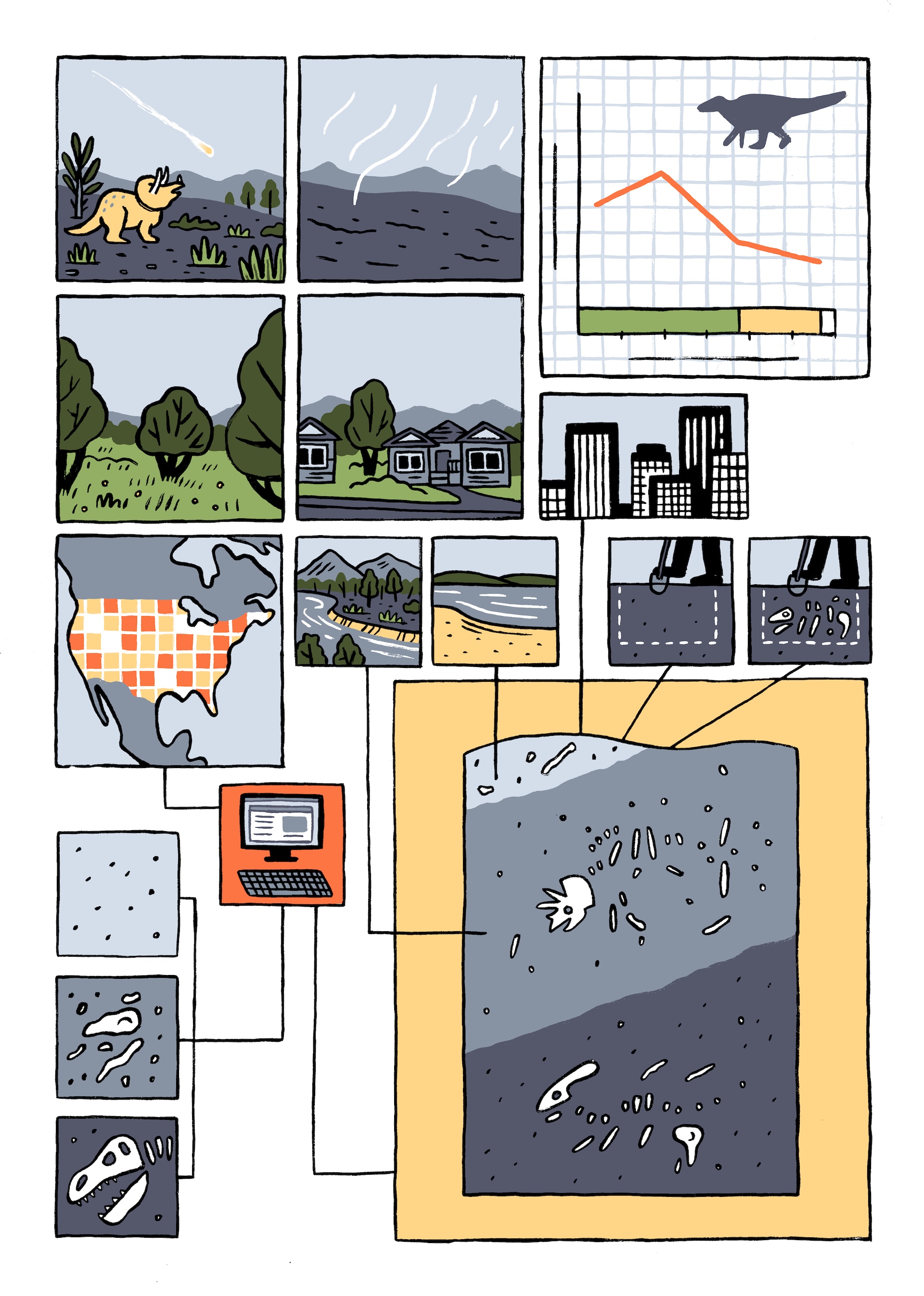

The dinosaurs were not in decline before the asteroid hit, a new study finds. Instead, poor fossilization conditions and unexposed late Cretaceous rock layers mean they're either not preserved or hard to find.

Dinosaurs weren't in decline when an asteroid smashed into Earth and wiped them out, scientists say. Instead, the idea that dinosaur diversity was declining before the asteroid struck 66 million years ago is likely based on faulty fossil data, according to a study that looked at nearly 18 million years of fossil evidence.

Fossil discoveries have long indicated that dinosaurs were shrinking in numbers and diversity prior to the asteroid impact at the end of the Cretaceous period. Previously, some researchers believed this was a sign that dinosaurs were already on the road toward extinction even before the cataclysmic encounter with a space rock. However, this idea has long been controversial, with other researchers arguing that dinosaur diversity was doing just fine at the time of their demise.

"It's been a subject of debate for more than 30 years — were dinosaurs doomed and already on their way out before the asteroid hit?" study lead author Chris Dean, a paleontologist at University College London, said in a statement.

Now, new research published Tuesday (April 8) in the journal Current Biology suggests that the apparent rarity of dinosaurs before their extinction may simply be due to a poor fossil record.

The scientists studied records of around 8,000 fossils from North America dating to the Campanian age (83.6 million to 72.1 million years ago) and Maastrichtian age (72.1 million to 66 million years ago), focusing on four families: the Ankylosauridae, Ceratopsidae, Hadrosauridae and Tyrannosauridae.

At face value, their analysis showed that dinosaur diversity peaked around 76 million years ago, then shrank until the asteroid strike wiped out the nonavian dinosaurs. This trend was even more pronounced in the 6 million years before the mass extinction, with the number of fossils from all four families decreasing in the geological record.

However, there is no indication of environmental conditions or other factors that would explain this decline, the researchers found. All of the dinosaur families were widespread and common, according to models developed by the researchers — and thus at low risk for extinction, barring a catastrophic event such as the asteroid impact.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rather, the Maastrichtian may have had poorer geological conditions for fossilization, the researchers suggested. Events such as the retreat of the Western Interior Seaway, which once ran from the Gulf of Mexico up through the Arctic, and the rise of the Rocky Mountains starting around 75 million years ago, may have impeded or disrupted fossilization, making it appear as if there were fewer dinosaurs and less diversity during that time.

The team also found that geological outcrops from the Maastrichtian of North America were not exposed, or were covered by vegetation. In other words, rock from this time that might hold dinosaur fossils was not readily accessible to researchers who were searching for the remains. Because half of the known fossils from this period are from North America, the study's findings may have global implications as well.

Among the 8,000 fossil records examined, the team found that Ceratopsians — a group that includes horned dinosaurs like Triceratops and its relatives — were the most common, probably because they inhabited plain regions that were most conducive to preservation during the Maastrichtian. Hadrosaurians — duck-billed dinosaurs — were the least common, possibly due to their preference for rivers. Reductions in river flow may have led to fewer depositions of sediment that could have preserved these dinosaurs, the researchers wrote in the study.

"Dinosaurs were probably not inevitably doomed to extinction at the end of the Mesozoic [252 million to 66 million years ago]," study co-author Alfio Alessandro Chiarenza, a paleontologist at University College London, said in a statement. "If it weren't for that asteroid, they might still share this planet with mammals, lizards, and their surviving descendants: birds."

Richard Pallardy is a freelance science writer based in Chicago. He has written for such publications as National Geographic, Science Magazine, New Scientist, and Discover Magazine.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.