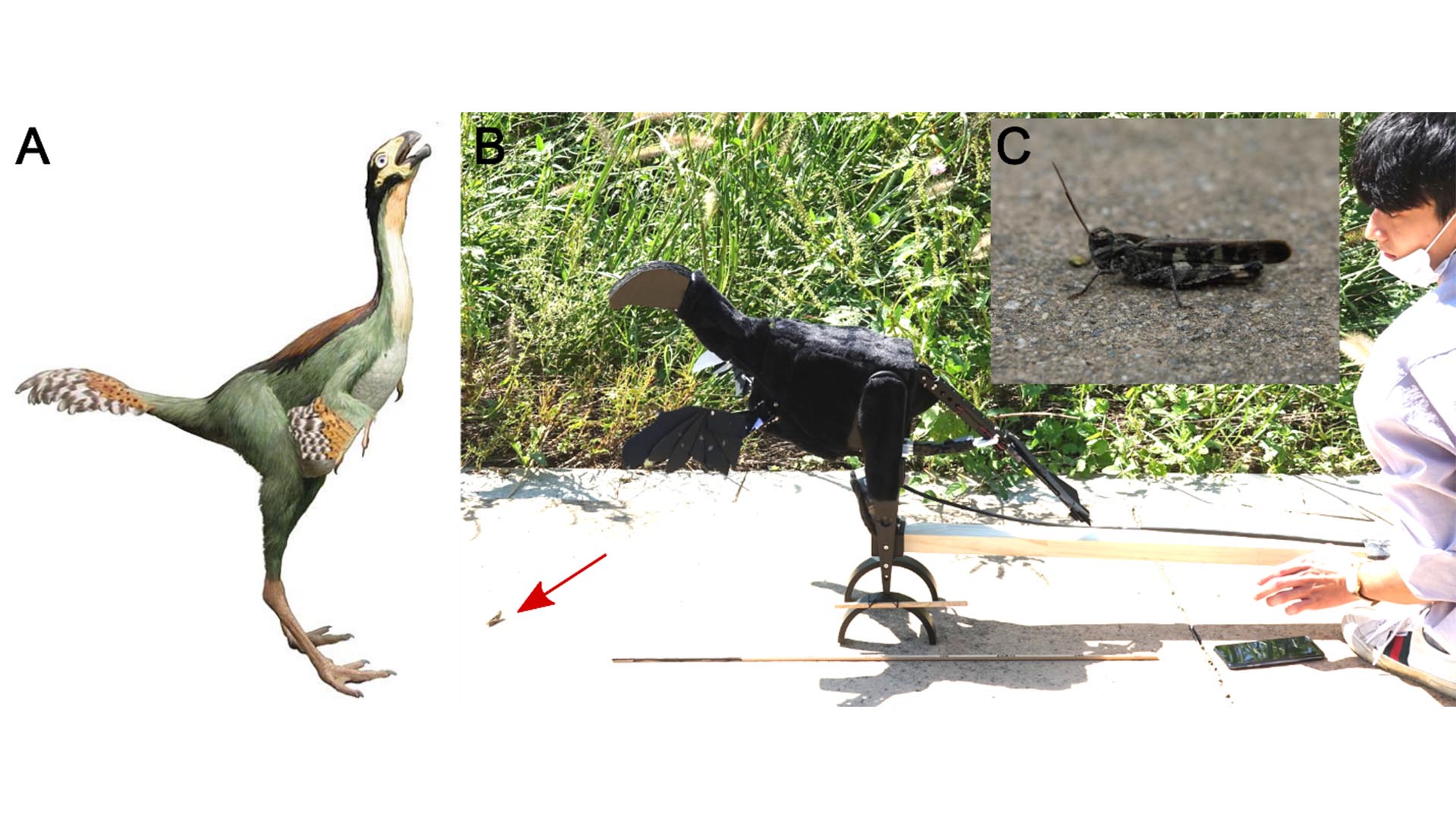

Scientists say their robot dinosaur could help explain the evolution of wings. But 1 expert says the study is flawed.

The robot faced up against grasshopper prey. But did the dinosaur it mimics actually eat insects?

A robot dinosaur is helping scientists peer into our prehistoric past to learn why some dinosaurs evolved feathered wings before they could fly. But one expert is skeptical that this robot can reveal much about the ancient predators, because there isn't yet evidence that the dino ate the prey these researchers tested.

Researchers built a metal robot with black felt and wheels, nicknamed Robopteryx, to resemble Caudipteryx, a peacock-size dinosaur with tiny feathered wings that roamed Earth about 125 million to 122 million years ago during the Early Cretaceous period (145 million to 100.5 million years ago). The researchers unleashed a flapping Robopteryx on a group of grasshoppers to test whether feathered-but-flightless dinosaurs may have evolved early wings to flush out prey from their hiding spots, according to a study published Thursday (Jan. 25) in the journal Scientific Reports.

"We propose that using plumage to flush prey could increase the frequency of chases after escaping prey, thus amplifying the importance of proto-wings and tails in maneuvering for successful pursuit," study author Sang-im Lee, an integrative animal ecologist at the Daegu Gyeongbuk Institute of Science and Technology in South Korea, said in a statement. "This could lead to the development of larger and stiffer feathers as these would enable more successful pursuits and more pronounced visual flush-displays."

Several modern-day birds, such as the greater roadrunner (Geococcyx californianus), use this "flush-pursuit" strategy. During their experiment, the researchers maneuvered a version of Robopteryx without wings near grasshoppers, and less than half of the insects dashed from the machine. In a separate trial, they added wing-like structures made of black-colored paper and sent Robopteryx flapping toward the grasshoppers. This time, 93% of the insects fled, which they believe shows that proto-wings may have been useful for dinosaurs when trying to reveal prey.

The problem? Scientists still aren't sure if Caudipteryx and other dinosaurs with proto-wings ate insects.

"I think it's great to see hypotheses like these tested quantitatively," Jingmai O'Connor, an associate curator of fossil reptiles at the Field Museum in Chicago who was not involved in the new study, told Live Science in an email. "However, I think it's worth noting that there is no actual evidence that any of these non-volant [flightless] feathered dinosaurs with protowings, like Caudipteryx and Anchiornis, were insectivorous!"

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"That is the only hiccup with this hypothesis but one that should certainly be considered," she added.

O'Connor led a 2019 analysis that compiled data from thousands of fossils from dinosaurs most closely related to birds to determine how the modern avian digestive system evolved. The researchers found that Caudipteryx seems to have eaten mostly plants, and Anchiornis — another flightless dinosaur with early wings — primarily ate lizards and fish.

"I think it means that the jury is still out on what protowings were for," O'Connor said. "Until we have supporting evidence these dinosaurs ate insects, it all remains highly hypothetical."

However, another paleontologist thinks these ancient dinosaurs may have had a more extensive diet than we can know for sure.

"The preservation of stomach content in extinct dinosaurs is very rare," Fion Ma, a vertebrate paleontologist at the National Museum of Natural History who was not involved in the new study, told Live Science in an email. "While there is no direct evidence indicating that feathered dinosaurs like Caudipteryx and Anchiornis hunted insects, I would not rule out such a possibility, as some of them were likely opportunistic feeders."

She added that she is "curious to see the experiment replicated using other animals, such as lizards, as fossil evidence shows that they were part of the diets of Anchiornis and Microraptor."

Kiley Price is a former Live Science staff writer based in New York City. Her work has appeared in National Geographic, Slate, Mongabay and more. She holds a bachelor's degree from Wake Forest University, where she studied biology and journalism, and has a master's degree from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.