Do all animals go through adolescence?

All species experience the bodily changes of puberty, but the social lessons that define the shift from childhood to adulthood are more nuanced.

Looking back on our teenage years often elicits a grimace — it's an awkward time, full of social faux pas, uncertainty and acne — but it's one that we all must pass through on our way to adulthood.

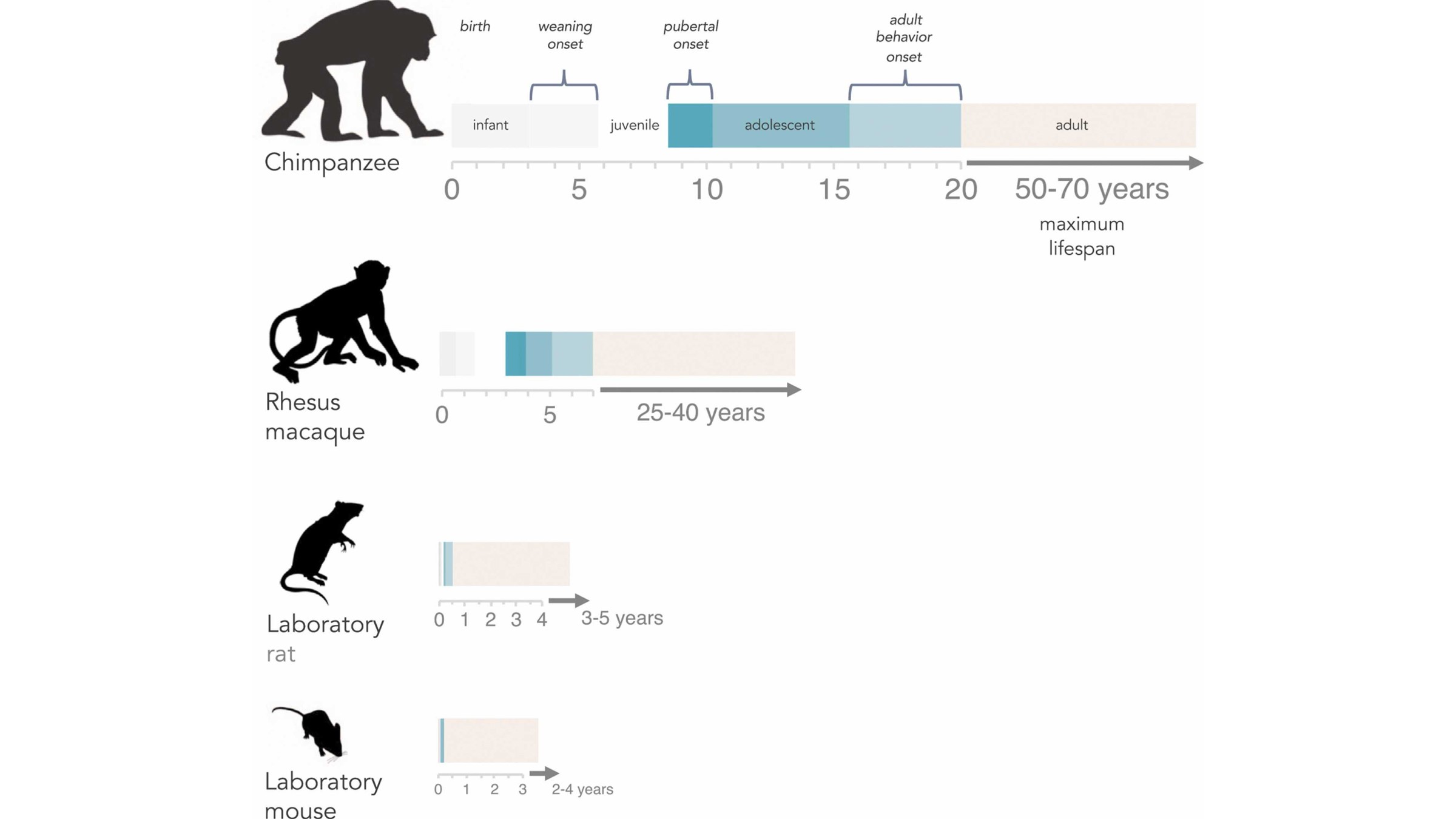

But do other animals also experience adolescence? This period of life comprises both physiological and social changes. Unquestionably, other animals experience puberty, the cascade of hormonal and physiological changes that enable mating. But researchers such as Dr. Barbara Natterson-Horowitz, a cardiologist and evolutionary biologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Harvard University, argue that most, if not all, animals experience a period of adolescence too — what Natterson-Horowitz calls "wildhood" — that also includes the social shifts that youngsters must navigate as they transition into adulthood.

For a long time, adolescence was thought to be unique to humans, Natterson-Horowitz told Live Science. "But the more you peel that back, the more you find that while there are certain aspects of adolescence that are uniquely human, that period of transition that starts with the onset of puberty and ends when a mature adult emerges — that's universal."

Perhaps not surprisingly, in the species that are most closely related to us, such as chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), some of these changes are easily recognizable to humans. Aaron Sandel, a biological anthropologist and primatologist at the University of Texas at Austin, published a paper showing that young chimps experience a growth spurt that leaves them clumsy as they adjust to their new bodies.

Related: Do any animals know their grandparents?

During adolescence, young Laysan albatross (Phoebastria immutabilis) learn intricate courtship behaviors by watching experienced adults and then practicing with their peers. — Barbara Natterson-Horowitz

At the same time, these juveniles are learning to integrate into adult society. They begin spending less time with their parents and more time with their peers, including members of the opposite sex. Young male chimps aren't aggressive during this time, deferring instead to the guidance of older adult chimps that serve as mentors and teach them social cues. "It's a period where you're really attentive to what will give you status and you're really attentive to what it means to be an adult," Sandel said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But do these characteristics extend beyond our closest relatives? Indeed, scientists have documented forms of adolescence across the animal kingdom that highlight how common this period may be.

Christine Ribic, a landscape ecologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, found that young grassland birds buck the "early bird gets the worm" trend and instead sleep late into the day, "mooching food off of their parents for as long as possible" before they finally go out on their own. Even after fledgling, young birds are not always self-sufficient. Other researchers have noted that, in challenging years, juvenile Gentoo penguins (Pygoscelis papua) return to their parents for help, mirroring a trend of young adults moving back in with their parents amid an economic downturn.

Animal experiments have also demonstrated how juveniles become more tolerant of risk. Young rats raised on the same nutritious diet as their mothers will intentionally choose to eat less-tasty foods, or even ones that make them sick, to fit in with a group of peers, and adolescent mice drink more alcohol among peers than they do when alone. When in groups, many animals — including fish, gazelles and bats — engage in predator inspection, in which packs of juveniles intentionally approach a predator. This group think is the same reason new drivers usually aren't allowed to drive with their friends in the car for a period of time after getting their license.

While we should be mindful of projecting our own biases and judgments onto other animals, probing these links between humans and their wild kin can be unifying and may help us navigate our own challenges, Natterson-Horowitz said.

"It really is recognizing that whatever struggles you may be going through, there's an animal and an evolutionary story behind them — that actually, adolescence has a function," which is to help animals survive and thrive in adulthood," she said. "Their struggles are not exactly the same as humans', but there are some pretty remarkable similarities in what they're going through."

Amanda Heidt is a Utah-based freelance journalist and editor with an omnivorous appetite for anything science, from ecology and biotech to health and history. Her work has appeared in Nature, Science and National Geographic, among other publications, and she was previously an associate editor at The Scientist. Amanda currently serves on the board for the National Association of Science Writers and graduated from Moss Landing Marine Laboratories with a master's degree in marine science and from the University of California, Santa Cruz, with a master's degree in science communication.