Pet cats arrived in China via the Silk Road 1,400 years ago, ancient DNA study finds

How and when domestic cats arrived in China has been a mystery. A new analysis of cat DNA suggests traders and diplomats likely carried the pets with them along the Silk Road 1,400 years ago.

China's first pet cats arrived in the country around 1,400 years ago — likely via the famous Silk Road trading route, ancient feline DNA reveals.

This new research — hailed as a "knockout study" — places the arrival of domestic cats in East Asia several hundred years later than previous studies. And it appears that the kitties were an instant hit with the local elite.

"Cats were initially regarded as prized, exotic pets," study co-author Shu-Jin Luo, a principal investigator at the Laboratory of Genomic Diversity and Evolution at Peking University in China, told Live Science in an email. "Cats' mysterious behaviors — alternating between distant and affectionate — added an air of mystique."

Modern domestic cats (Felis catus) descend from African wildcats (Felis silvestris lybica). Previous research suggests these felines began living alongside humans in the Middle East roughly 10,000 years ago, before evolving and then spreading to Europe about 3,000 years ago, according to the new study.

Around A.D. 600, merchants and diplomats first transported domestic cats in small crates and cages from the eastern Mediterranean through Central Asia, Luo said. These traders and officials brought just a handful of the pets to China, offering them as tribute to members of the elite, she said.

Related: Lasers reveal secrets of lost Silk Road cities in the mountains of Uzbekistan

Archaeological evidence shows that long before the arrival of domestic cats in China, people in rural Chinese communities lived alongside native leopard cats (Prionailurus bengalensis). Researchers have previously found leopard cat bones dating to 5,400 years ago in an ancient farming village in the northwestern Shaanxi province, indicating that humans and cats co-existed in settlements together.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But this relationship was not equivalent to cat domestication, the authors of the new study argued. Moreover, the common assumption that cat domestication took place in China during the Han Dynasty between 206 B.C. and A.D. 220 also lacks support, as there are no archaeological remains of pet cats from that period. Therefore, a complete re-evaluation of when and how domestic cats came to China is required, the researchers said in the study.

'A highly challenging task'

To address these questions, Luo and her colleagues analyzed 22 feline remains from 14 archaeological sites in China spanning a period of about 5,000 years. The researchers first sequenced nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in the bones to determine each species. Then, the researchers compared these results with previously published data from 63 nuclear and 108 mitochondrial genomes that summarize the evolution of cat genetics worldwide.

"This is by far the largest and most comprehensive study on small felids living closely with humans in China," Luo said. "Assembling the archaeological samples of cat remains from China across this time period [was] a highly challenging task."

Fourteen of the 22 feline bones from China belonged to domestic cats, according to the study, which was uploaded Feb. 5 to the preprint database BioRxiv and has not yet been peer reviewed. The oldest of these pet cat remains originated from Tongwan City in Shaanxi and was radiocarbon dated to A.D. 730, suggesting that domestic cats arrived in China long after the Han Dynasty had ended.

The 14 domestic cats in the sample all shared a genetic signature in their mitochondrial DNA known as clade IV-B. This signature is rare among domestic cats from Europe and Western Asia, but the researchers found a close match in the previously published data about a cat that lived sometime between A.D. 775 and 940 in the city of Dhzankent, Kazakhstan.

The Dhzankent cat is the oldest-known domestic cat along the Silk Road, offering tantalizing clues about the origins of domestic cats in China. The Silk Road's heyday lasted between A.D. 500 and 800, hinting that merchants likely transported the kitties to East Asia along this route.

Rare coat colors

The cats that merchants and diplomats initially gifted to the Chinese elite were likely all-white cats or mackerel-tabby cats with white patches, the researchers noted in the study. DNA from the Tongwan City cat suggested it was a healthy male with a long tail and short, either all-white or partially white fur, they said. Even today, the proportion of white cats is higher in East Asia than elsewhere in the world, the researchers added.

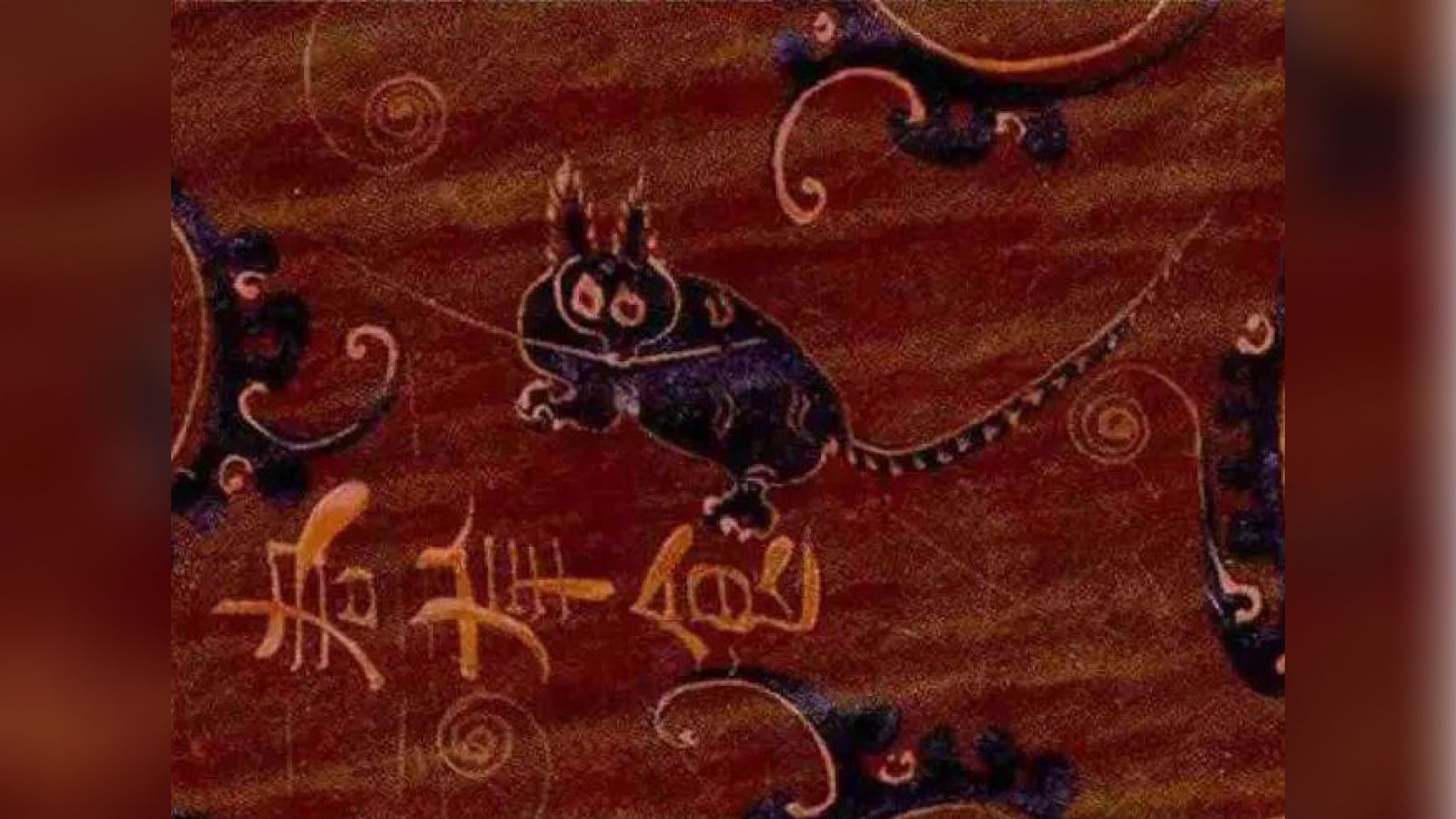

Domestic cats became so popular following their introduction to China that people incorporated them into Chinese folk religion, Luo said. "Ancient Chinese people even performed specific religious rituals when bringing a cat into their homes, viewing them not as mere possessions but as honored guests," she said.

Melinda Zeder, an archaeozoologist at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History who was not involved in the new research, told Science magazine that the work offers valuable insights into how domestic cats made it to China. "Tying them to the Silk Road is really boffo," Zeder said. "It's a knockout study."

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.