Elephants' giant, hot testicles could stop them getting cancer

Scientist claims elephants' cancer-preventing genes may have evolved to protect their sperm from the scorching hot habitats they live in.

Elephants rarely get cancer, and their giant, hot testicles might provide a clue as to why.

The idea comes down to a protein called p53, which helps prevent DNA damage in cells — including damage that could turn a normal cell into a cancerous cell.

Elephants, unlike humans, have multiple copies of the gene that encodes p53 — meaning, the gene that provides the “recipe” for the body to make the protein. Fritz Vollrath, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Oxford, said this could help to protect their sperm from hot temperatures.

This hypothesis starts with "Peto's paradox," Vollrath told Live Science.

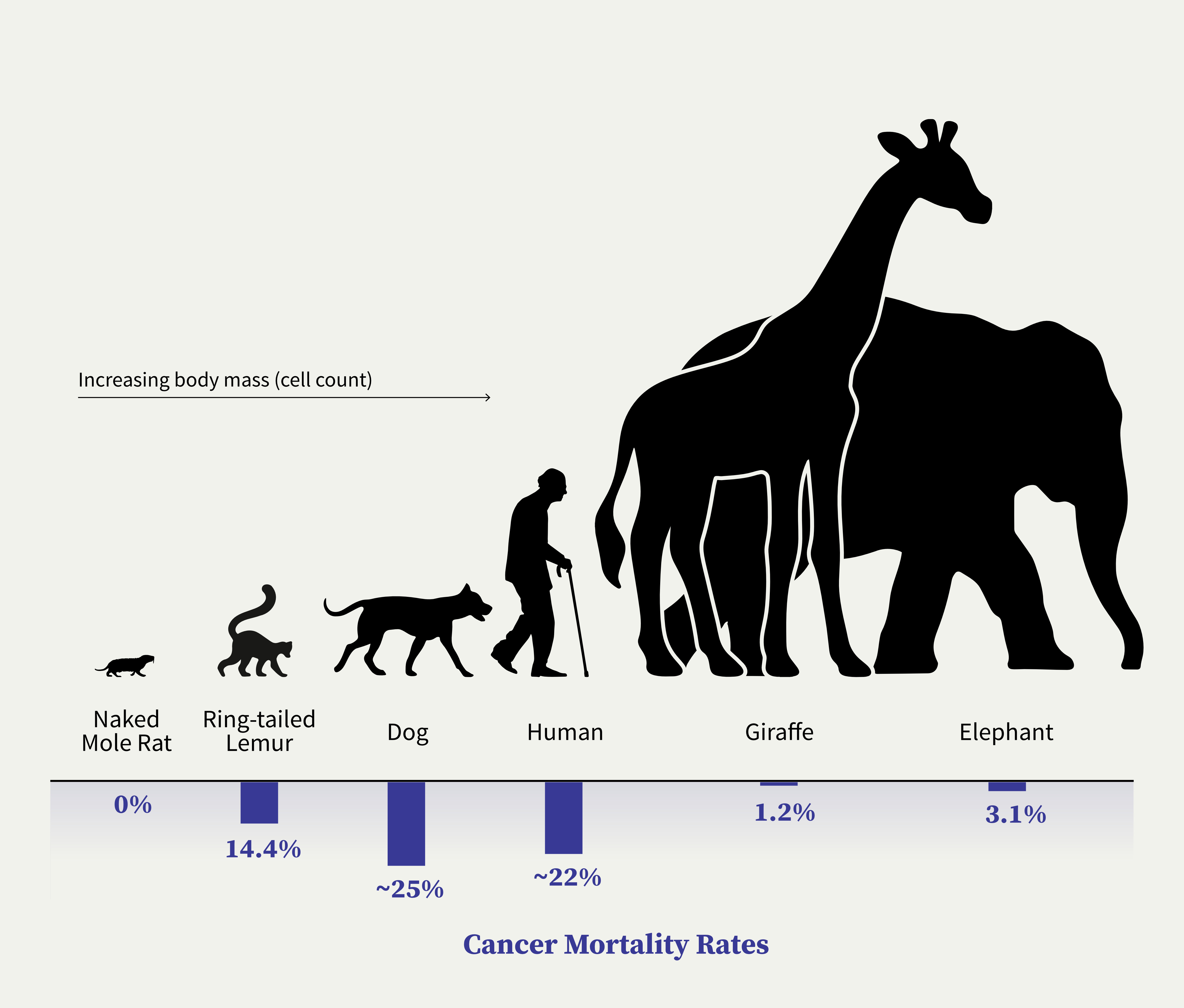

In the 1970s, an epidemiologist named Richard Peto described a puzzling phenomenon: Large animals, despite having many more cells that could potentially turn into cancerous cells, don't seem to have a higher risk of developing cancer than smaller animals. This is particularly astounding in elephants — they are statistically less likely to develop cancer than humans, despite being many times our size.

Related: Do elephants really 'never forget'?

A few years ago, researchers found that elephants have 20 copies of the gene that encodes the p53 protein. Humans, in comparison, have just one. The protein essentially works like a copy editor, reviewing genetic material as cells multiply and potentially killing off cells with any damages that could lead to cancer. As elephants have multiple copies of the gene that encodes p53, they could have multiple rounds of "copy-editing," which could vastly reduce the risk of a damaged cell surviving.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But why did elephants evolve 20 copies of this gene? Vollrath thinks it has to do with their testicles. Many male animals, including humans, have their testicles partially outside their body to cool them down, which is believed to be important for creating a healthy batch of sperm. The reasons for this are unclear, though it may have something to do with increased DNA damage at higher temperatures.

Through a quirk of evolutionary history, however, elephant testicles are located inside their bodies. As multi-ton, dark gray animals walking around in the sun, their testicles have the potential to get really hot — and therefore the elephants may have trouble making viable sperm. But if they had more copy-editing proteins, the theory goes, that hot sperm could be protected from damage..

Vollrath published this hypothesis as a note in the journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution on June 27.

It is hard to assess why exactly a particular trait might have evolved in a species, Vincent Lynch, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Buffalo, who was not involved in developing this new hypothesis, told Live Science.

It's possible that multiple copies of the p53 gene evolved to protect elephant sperm from hot temperatures. But it's also possible that those multiple copies evolved because elephants are big animals so are potentially more susceptible to cancer, Lynch said. It could also be both things at once.

Other large animals don't have multiple copies of the p53 gene. Whales, for example, are large animals with internal testicles, but they seem to have just one copy. But whales also have an internal system to cool their testicles down, Vollrath noted – plus, it doesn’t get as hot in the water.

Similarly, animals closely related to elephants, such as hyraxes, also have internal testicles. But these animals are much smaller than elephants, and small animals are way more efficient at dissipating heat than large animals, Lynch said.

No matter how it evolved, elephants seem to have a way of naturally circumventing cancer — and studying how it works may help us understand more about the disease, Vollrath said.

Ethan Freedman is a science and nature journalist based in New York City, reporting on climate, ecology, the future and the built environment. He went to Tufts University, where he majored in biology and environmental studies, and has a master's degree in science journalism from New York University.