25 million-year-old 'slasher' dolphin with weird teeth discovered in museum collection

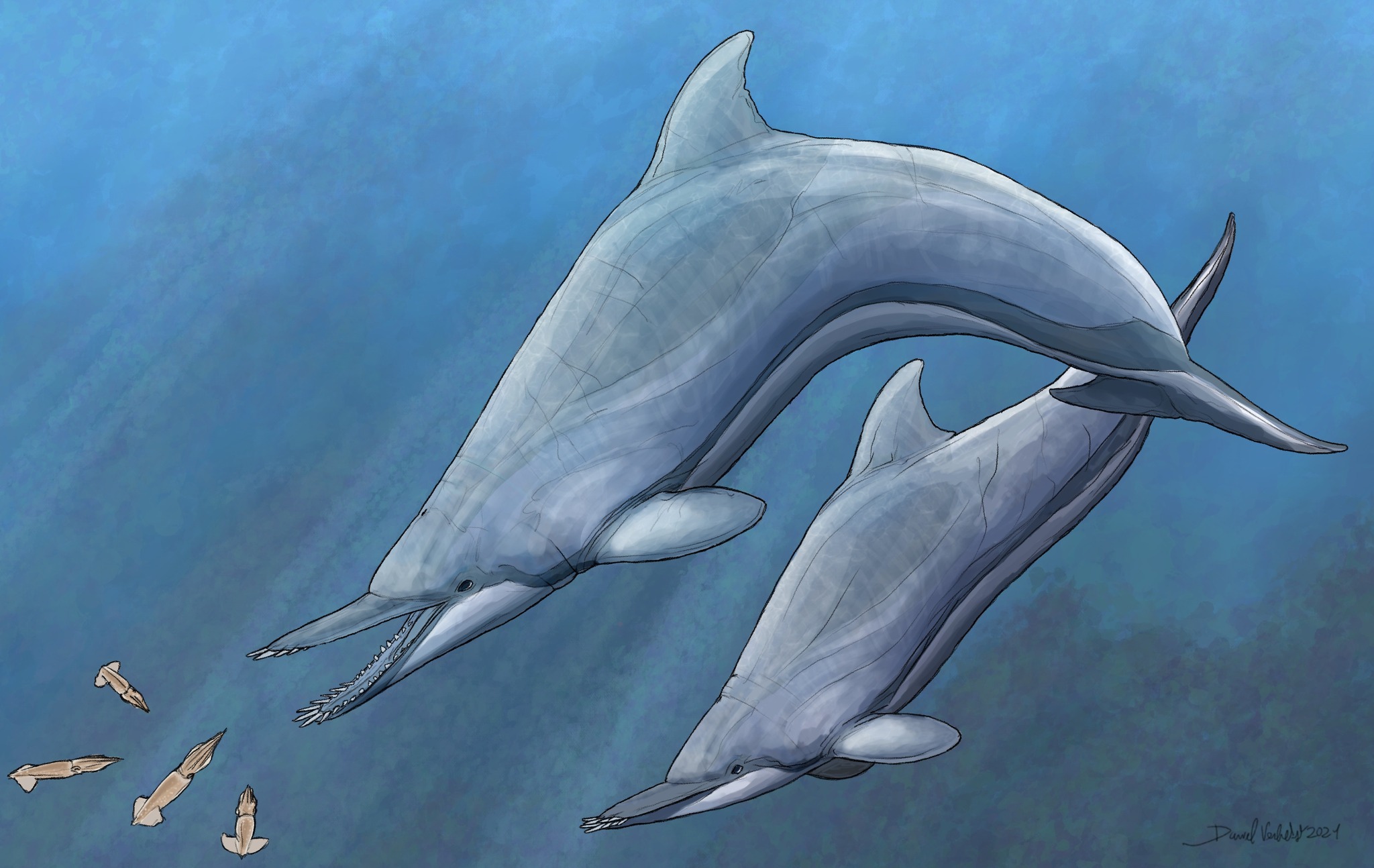

Researchers believe the creature, named Nihohae matakoi, used its horizontal teeth to thrash at prey before gulping it down.

A bizarre predatory dolphin that lived 25 million years ago and had long, sharp teeth jutting straight out from its snout has been discovered in a museum collection in New Zealand.

The toothy animal lived during the late Oligocene epoch (34 million to 23 million years ago). Scientists described the extinct dolphin from a near-complete skull found in a cliff face in New Zealand's South Island in 1998. They named the species Nihohae matakoi, from Maori words meaning "slashing teeth, face sharp."

Ambre Coste, a researcher at the University of Otago in New Zealand and lead author of a study on the dolphin, had noticed the strange skull in the collection and realized how well preserved and complete it was. "That's what made this skull so interesting," she told Live Science.

The skull, which is around 2 feet (60 centimeters) long, has regular, vertical teeth in the part of the jaw closer to the face, and flat, long teeth closer to the snout. These longer teeth, measuring between 3.1 and 4.3 inches (8 to 11 cm) seemed to jut out almost horizontally.

Related: Megalodon was a warm-blooded killer, but that may have doomed it to extinction

The flat teeth also don’t interlock, so the mouth is “nothing that would catch a fish,” said Coste.

Close examination of the teeth showed very little wear and tear, suggesting it is unlikely the animal was rooting around in the sand for food.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

So what were these spade-like teeth for? To find out, the researchers considered the behavior of modern animals that have teeth jutting out from their faces: sawfish.

Sawfish (Pristidae) are rays with snouts that look like long, flat chainsaws. According to a 2012 study in the journal Current Biology, juvenile sawfish "thrash" at food by hitting them with their teeth. "They just whack their heads back and forth," Coste said. "And that will injure or stun and kill that sort of prey, so then it’s easier to go and slurp it up."

The researchers believe N. matakoi may have done the same. This idea is supported by N. matakoi's cervical vertebrae, or neck bones, which were also part of the museum collection. Unlike many modern dolphins, these neck bones weren’t fused, meaning the animal had a bigger range of motion in its neck than many modern dolphins. This greater range of movement would likely have helped the dolphins to thrash their prey to death.

Because there wasn’t much wear on N. matakoi’s teeth, the scientists suspect the dolphins didn’t eat fish with hard bones or scales. Instead, the animals would likely have eaten soft-bodied animals like squids and octopuses.

It’s also possible the teeth had some sexual or social function, although this would be difficult to test, the study said.

The team said the use of these strange jutting teeth should be investigated further to understand why they evolved — and why teeth like this keep appearing in different groups of animals.

The study was published June 14 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Kristin Hugo is a science journalist with a focus on biology, nature, animals, and bones. After earning a BA in Journalism from CSU Northridge and an MS in Science Journalism from Boston University, Kristin worked as a science writer for National Geographic, PBS Newshour, Newsweek, Bay Nature Magazine, and more. Kristin also has experience in fact-checking, social media, video production, photography, and illustration.

Kristin's current main project is writing a book for MIT Press about dead animals, called "Carcass: On the Afterlives of Animal Bodies."