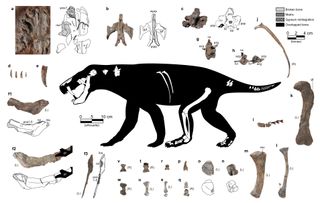

270 million-year-old saber-toothed predator from 'ghost' lineage looked like a bald dog

Fossils of the oldest saber-toothed predator are helping researchers understand the evolution of early mammal relatives called gorgonopsians and our shared origins in the therapsid group.

Scientists have uncovered what they believe to be the oldest saber-toothed animal on record — a furless, husky-sized predator from a "ghost" lineage of ancient mammal relatives.

This strange creature is thought to have lived around 280 million to 270 million years ago and may help scientists unlock the secrets of our ancient family tree.

Researchers unveiled the fossilized remains of the animal on Tuesday (Dec. 17) in the journal Nature Communications. And while they couldn't determine its species, the animal belonged to a branch of ancient mammal relatives called the gorgonopsians.

Gorgonopsians weren't a direct ancestor of living mammals, nor did they give rise to the saber-toothed cats that existed until around 10,000 years ago. However, they were part of the wider therapsid group, which had some mammal-like features and eventually gave rise to mammals.

Related: 35,000-year-old saber-toothed kitten with preserved whiskers pulled from permafrost in Siberia

Study co-author Kenneth D. Angielczyk, a curator of paleomammalogy at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, told Live Science in an email that the oldest therapsid fossils are about 270 million years old, but researchers think they probably evolved around 300 million years ago.

That means there's a gap in the fossil record, which the study authors describe as a "ghost lineage." At about 280 million to 270 million years old, the newly discovered gorgonopsian is a member of that missing lineage.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Our new gorgonopsian helps to fill in a major time gap in the fossil record of ancient mammal relatives," Angielczyk said.

Researchers discovered the new gorgonopsian fossils on the Spanish island of Mallorca. In the age of the gorgonopsians, this Mediterranean island would have been part of the ancient supercontinent Pangaea, according to a statement released by the Field Museum.

The fossilized remains included fragments of a skull, serrated blade-like teeth, jaw bones, ribs, and a hind leg. From these bones, the researchers deduced that the predator would have been around the size of a dog.

Angielczyk and his colleagues think that the fossils belong to a previously unknown species. However, because they are so fragmented, the team couldn't find enough unique features to be sure.

"Although the specimen has a number of features that let us confidently identify it as a gorgonopsian, it is too fragmentary for us to determine if it is definitely a new species or a member of a previously described species," Angielczyk said. "If we eventually found a more complete specimen, it would be great to eventually give it a formal species name."

Therapsid evolution

Even though there's uncertainty surrounding where the creature sits on the gorgonopsian family tree, its discovery helps scientists piece together the origins of gorgonopsians, and by extension, the larger therapsid group. The fossils are older than the oldest known gorgonopsian and potentially the oldest known therapsid — Raranimus dashankouensis, according to the study.

This gorgonopsian, with its nasty gnashers, would have been a top predator in its day and demonstrates that therapsids were diversifying into different forms earlier than previous fossils have shown.

"[Diversification of therapsids] was well underway by about 280 million years ago, which is farther in the past than previously thought, and may have happened in the aftermath of an extinction event that removed previous competitors," Angielczyk said.

Patrick Pester is the trending news writer at Live Science. His work has appeared on other science websites, such as BBC Science Focus and Scientific American. Patrick retrained as a journalist after spending his early career working in zoos and wildlife conservation. He was awarded the Master's Excellence Scholarship to study at Cardiff University where he completed a master's degree in international journalism. He also has a second master's degree in biodiversity, evolution and conservation in action from Middlesex University London. When he isn't writing news, Patrick investigates the sale of human remains.