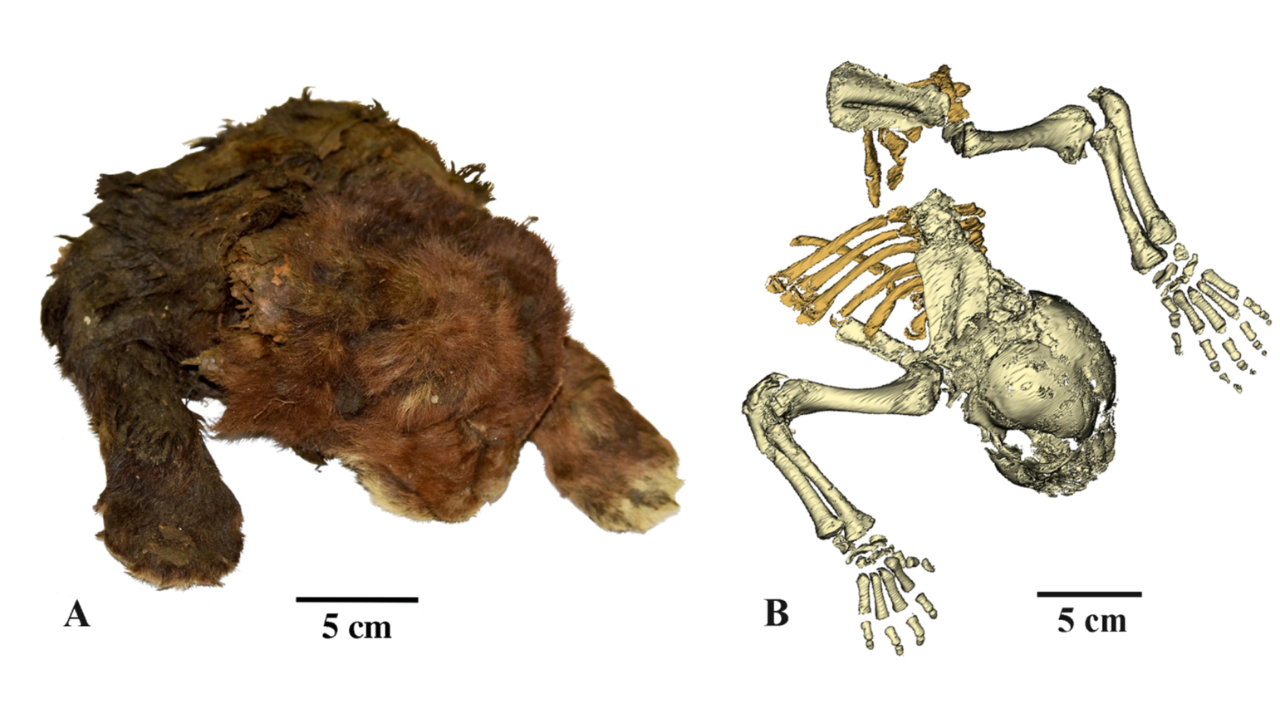

35,000-year-old saber-toothed kitten with preserved whiskers pulled from permafrost in Siberia

Researchers have analyzed mummified remains pulled from Siberia's permafrost in 2020 and determined they belong to a 3-week-old saber-toothed kitten that died at least 35,000 years ago.

Researchers have pulled the mummy of a newborn saber-toothed cat that died at least 35,000 years ago from Siberia's permafrost — and the kitten still has its whiskers and claws attached.

A new analysis of the kitten's stunningly-preserved head and upper body shows it was just 3 weeks old when it died in what is now Russia's northeastern Sakha Republic, also known as Yakutia. Scientists found pelvic bones, a femur and shin bones encased in a block of ice together with the mummy. The circumstances of the animal's death are unknown.

It is extremely rare to find well-preserved remains of saber-toothed cats, and this one belongs to the species Homotherium latidens, according to a study published Thursday (Nov. 14) in the journal Scientific Reports. Saber-toothed cats of the extinct genus Homotherium lived across the globe during the Pliocene (5.3 million to 2.6 million years ago) and early Pleistocene (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago) epochs, but evidence suggests this group became less widespread toward the end of the Pleistocene (also known as the last ice age).

"For a long time, the latest presence of Homotherium in Eurasia was recorded in the Middle Pleistocene [770,000 to 126,000 years ago]," researchers wrote in the study. "The discovery of H. latidens mummy in Yakutia radically expands the understanding of distribution of the genus and confirms its presence in the Late Pleistocene [126,000 to 11,700 years ago] of Asia."

Related: 32,000-year-old mummified woolly rhino half-eaten by predators unearthed in Siberia

The small, deep-frozen mummy shows H. latidens was well-adapted to ice age conditions, according to the study. The researchers compared the carcass to that of a modern 3-week-old lion (Panthera leo) cub and found the saber-toothed kitten had wider paws and no carpal pads — pads on the wrist joint that act as shock absorbers in today's felines. These adaptations enabled saber-toothed cats to walk with ease in snow, while thick, soft fur observed on the mummy shielded the predators against polar temperatures.

The comparison with the lion revealed that saber-toothed cats had a larger mouth, smaller ears, longer forelimbs, darker hair and a much thicker neck. Researchers already knew from studying the skeletons of adult Holotherium that these saber-toothed cats had short bodies and elongated limbs, but the new research shows these features were already present at the age of 3 weeks.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Radiocarbon dating of the mummy's fur suggested the kitten has been buried in permafrost for at least 35,000 years, and possibly 37,000 years. The carcass was pulled from the banks of Yakutia's Badyarikha River in 2020, and its discovery has enabled researchers to describe, for the first time, physical characteristics of H. latidens, including the texture of these cats' fur, the shape of their muzzle and the distribution of their muscle mass.

Remarkably, the mummy still had sharp claws and whiskers (or vibrissae) attached to it. However, "the mummy eyelashes were not preserved," the researchers noted in the study.

The new analysis identified the species the mummy belongs to and its most striking features, but its authors are already working on a new paper. "The anatomical features of the find will be discussed in more detail in a subsequent paper," they wrote.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus