500 million-year-old 'abnormal shrimp' used facial spikes to 'pincushion' soft prey

Scientists have solved the mystery of what Anomalocaris canadensis, an extinct apex predator, may have eaten.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Around 500 million years ago, an apex predator no larger than a house cat terrorized the seas in search of prey to puncture with its spiky facial appendages.

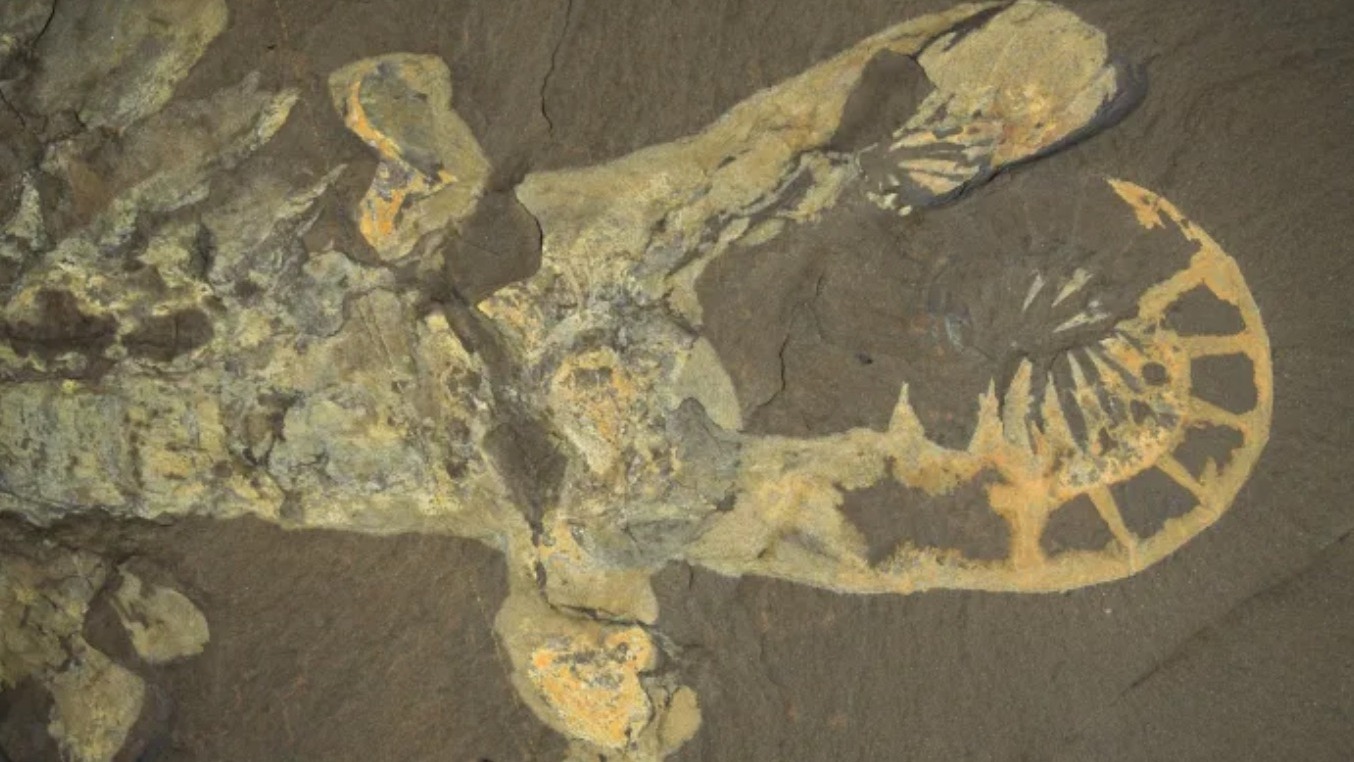

For years, paleontologists thought that the arthropod Anomalocaris canadensis, whose name roughly means "the abnormal shrimp from Canada," used its spears to pierce trilobites and other hard-shelled prey. However, a new study finds that this Cambrian critter likely hunted soft-bodied animals instead, according to a study published July 5 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

"There had been a long-standing question about what was causing the injuries we were seeing on Cambrian trilobites [in the fossil record of Canada's well-preserved Burgess Shale]," lead author Russell Bicknell, a postdoctoral researcher at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, told Live Science. "It had been hypothesized that A. canadensis was possibly one of the animals that was causing the damage by using its spiky appendages to grab and pierce its prey."

Related: Ancient armored 'worm' is the Cambrian ancestor to three major animal groups

The shrimp-like A. canadensis reached lengths of about 3 feet (1 meter), which included its two fearsome facial appendages. Previously, another team of researchers suggested that tough trilobites weren't part of this apex predator's diet, according to bite force models. But the new team took a different approach.

The scientists created 3D computer models of A. canadensis based on existing fossil evidence and also looked at animals that could stand in as modern-day analogues of the Cambrian beast, such as whip spiders (part of the arachnid order Amblypygi) and whip scorpions (Uropygi). They studied how these modern arthropods used their appendages to grab and hold prey.

The team concluded that, while A. canadensis might have been adept at grabbing animals, the animal's two facial appendages would've been too delicate to actually pierce through trilobites' tough exoskeletons, which Bicknell said would have "possibly been made up of a similar chemical composition as the cuticle of a horseshoe crab's exoskeleton."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We showed that the spikes on the appendages probably would've been damaged if it were to try to deal with harder prey," Bicknell said.

Instead, the researchers determined that this ancient hunter targeted soft-bodied animals swimming and floating within the water column.

"This animal probably swam like cuttlefish, with its appendages outstretched in front of it and its flaps undulating to help it accelerate through the water," Bicknell said. "It would then grab its prey and puncture it as if it were a pincushion."

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus