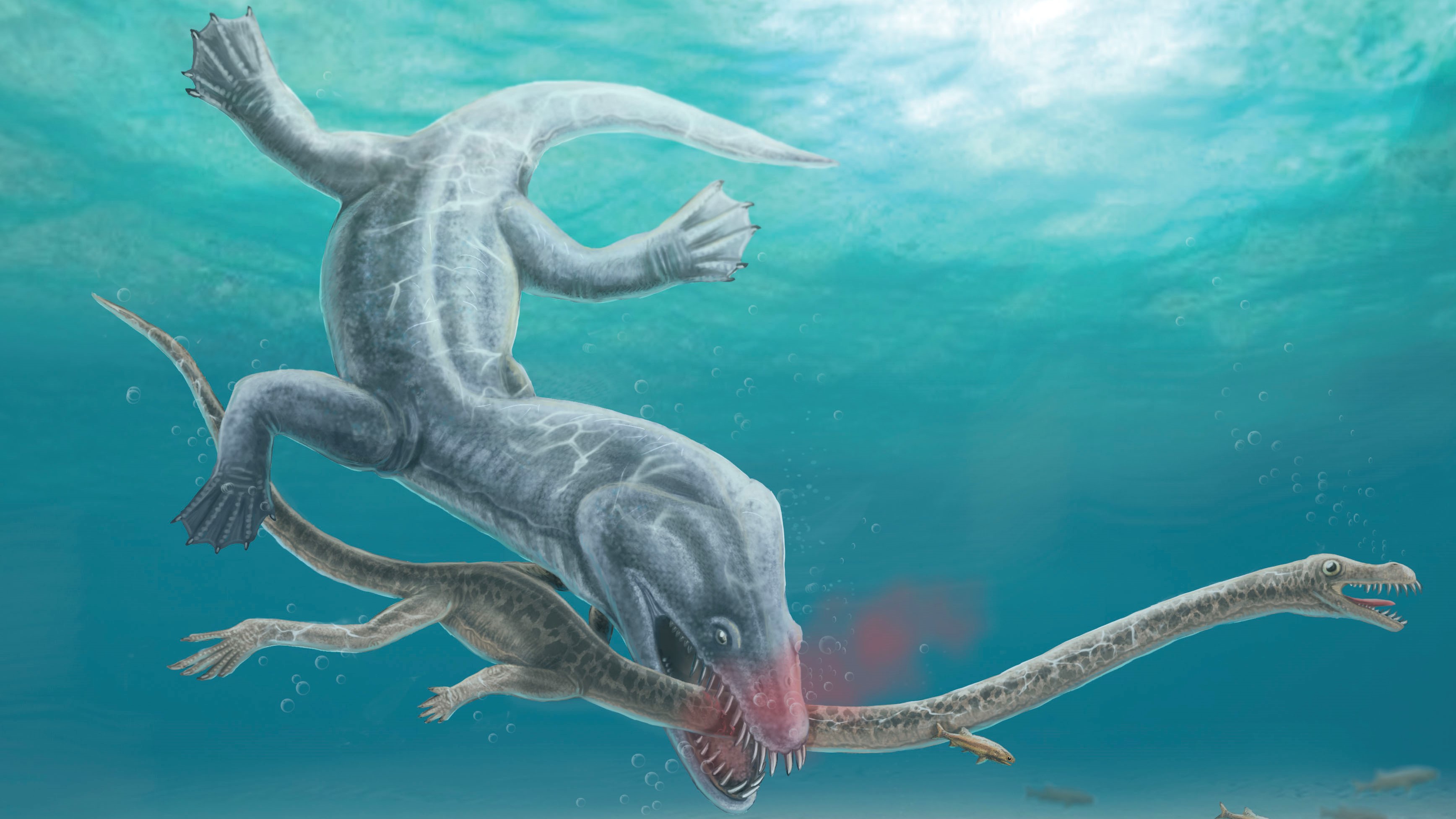

Enormous 240 million-year-old sea monster had its head torn off in one clean bite

Analysis of bite marks on Tanystropheus hydroides, which lived during the Middle Triassic, showed another predator had attacked from above and torn its neck in two.

A giant predator that lived 240 million years ago was decapitated with a single, brutal bite from a deadlier creature, scientists have said.

The beheaded animal, which had its neck ripped in half during the attack, belonged to the species Tanystropheus hydroides — a marine reptile that could grow to 19.5 feet (6 meters) long. It was an ambush predator, feasting on fish and squid in what was a tropical lagoon during the Middle Triassic (247 to 237 million years ago).

Tanystropheus had extremely long necks; in some cases their necks were three times as long as their torsos. The decapitated animal came from the Monte San Giorgio fossil site, which sits on the border of Switzerland and Italy and boasts a huge record of marine life from the Middle Triassic.

Stephan Spiekman, a vertebrate paleontologist at the State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart, in Germany, was studying two Tanystropheus specimens as part of his doctoral work at Switzerland's Paleontological Museum of the University of Zurich. The first belonged to T. hydroides, while the second was T. longobardicus — a smaller species that was around 5 feet (1.5 m) long.

A closer look at the fossils showed the necks had been severed, with clear bite marks on some of the vertebrates.

Spiekman and Eudald Mujal, a paleontologist at the State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart, analyzed the bite marks and bone breaks to work out what had happened to these ancient creatures. The findings suggest they were attacked by another predator that appears to have targeted their long necks as a weak point on the body.

Related: Weird 'broomstick' necked Triassic reptile named after mythical Greek sea monster

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We found two tooth punctures exactly where the neck is broken, and the neck is broken in a single, diagonal plain," Spiekman told Live Science in an email. "This suggests that the neck was bitten off in a single bite." He added there may have been a few preliminary bites that did not hit the bone, but "it is very plausible that a large predator bit [off] the neck in one go, especially considering the large predators that were around in that environment."

In a new study published Monday (June 19) in Current Biology, the researchers found evidence to suggest the attack happened from above, with the predator swooping down and biting the neck to decapitate the Tanystropheus. There was no trace of the bodies, but the heads and what remained of the necks were very well preserved. This indicates the predator targeted the long necks to quickly kill the Tanystropheus so it could feast on their meaty bodies.

List of potential killers

What creature could have killed a 20-foot-long ambush predator? Spiekman said the huge diversity at Monte San Giorgio means the list of potential killers is substantial. By measuring the distance between the tooth punctures, the scientists could compare the bite size to the large predators that lived in the area at the time.

"This left us with a final list of suspects," Spiekman said. These include Cymbospondylus buchseri — a large, early ichthyosaur that could grow up to around 18 feet (5.5 m) — and Nothosaurus giganteus — an enormous reptile that grew up to 23 feet (7 m). The third possibility is Helveticosaurus zollingeri, a "very enigmatic" 12-foot-long (3.6 m) predator with powerful forelimbs, a flexible tail and a strong, toothy snout.

The researchers said that although Tanystropheus' long necks were a weak point, reptiles persisted with stiff, long necks for around 175 million years, suggesting it played an important role during the Triassic period.

"The fact that we have two species of Tanystropheus at Monte San Giorgio with different sizes and diets … shows that their long, stiff necks were quite multifunctional," Spiekman said.

"We think the relatively small heads and long necks would have helped Tanystropheus ambush its prey, since in water with low visibility this head would be very difficult to spot for any prey. Also, by sticking to the shallow water, Tanystropheus possibly was able to avoid large predators… most of the time."

Hannah Osborne is the planet Earth and animals editor at Live Science. Prior to Live Science, she worked for several years at Newsweek as the science editor. Before this she was science editor at International Business Times U.K. Hannah holds a master's in journalism from Goldsmith's, University of London.