11 jaw-dropping fossil discoveries that weren't dinosaurs in 2023

Move over, dinosaurs: It's time for some of our favorite non-dino fossil stories of 2023 to shine.

Dinosaurs often steal the limelight when it comes to fossils, but other prehistoric critters are just as deserving of our attention. As 2023 comes to a close, it's time to look back on some of the most jaw-dropping fossil discoveries that weren't all about T. rex. From a fish with eyes too big for its stomach to the largest ever fossilized flower and mysterious marine fossils that glow gold, here's our pick of non-dino fossils that blew our socks off in 2023.

Largest penguin to walk Earth

In February, scientists described fossils belonging to the largest known species of penguins — Kumimanu fordycei, which weighed a whopping 340 pounds (154 kilograms). These colossal penguins glided through the ocean around what is now New Zealand more than 50 million years ago, bones discovered inside beach boulders in North Otago on the country's South Island revealed.

Researchers estimated the weight of K. fordycei based on the size and density of these bones compared with those of living penguins. The fossilized remains of eight other penguin specimens were also uncovered inside the boulders, including those of the newfound species Petradyptes stonehousei and a known species of giant penguin, K. biceae.

Giant penguins likely disappeared around 27 million years ago, when they were outcompeted by marine mammals similar in size, experts told Live Science.

Tiny penguin skulls

In June, researchers identified two tiny skull fossils from New Zealand's North Island as belonging to a never-before-seen extinct species, which they named Wilson's little penguin (Eudyptula wilsonae). The skulls, one from an adult and the other from a juvenile, were remarkably similar to those of the smallest living species of penguin today — the little penguin (Eudyptula minor).

Researchers don't know exactly how small the extinct birds were, but little penguins grow to a maximum size of 13.5 inches (35 centimeters) and weigh around 2 pounds (0.9 kg), which may be in the ballpark.

Related: Ancient skeletons of largest-ever marsupial unearthed in Australia

Fossilized flower mystery solved

In January, scientists finally got to the bottom of a 150-year-old mystery. They discovered that a flower entombed in a hunk of amber and discovered in the Baltic forests of Northern Europe in 1872 is a newfound species named Symplocos kowalewskii that dates to the late Eocene epoch (roughly 38 million to 33.9 million years ago).

The specimen, which measures about 1 inch (2.8 cm) wide, is the largest fossilized flower ever recorded and is three times the size of the next-biggest amber-encased bloom.

Trilobites' hidden third eye

Scientists examining a fossilized trilobite specimen — an extinct marine arthropod that lived during the Paleozoic Era (541 million to 252 million years ago) — discovered that these prehistoric creatures didn't have just a pair of compound eyes, as previously thought, but also sported a third eye in the middle of their forehead.

The trilobite specimen was missing a part of its head, which gave researchers a glimpse under a layer of shell that becomes opaque during the fossilization process and obscures the structures beneath. Hidden median eyes are common among arthropods living today.

Baby turtles mistaken for plants

A re-examination of two ancient "plant" fossils discovered in Colombia 50 years ago revealed they are actually the remains of hatchling turtles from the dinosaur age. The 2-inch-long (5 cm), leaf-shaped fossils fooled their finder, who originally placed them within a group of plants that thrived during the Late Devonian (419.2 million to 358.9 million years ago) and the Permian (298.9 million to 251.9 million years ago).

In December, it turned out the fossils were extremely rare imprints of the upper shells of baby turtles dating back to the Aptian age (125 million to 113 million years ago) of the Cretaceous (145 million to 66 million years ago).

It's possible the hatchlings were members of the oldest sea turtles on record — Desmatochelys padillai — but researchers would need a complete skeleton to confirm this.

Related: Flesh-eating 'killer' lampreys that lived 160 million years ago unearthed in China

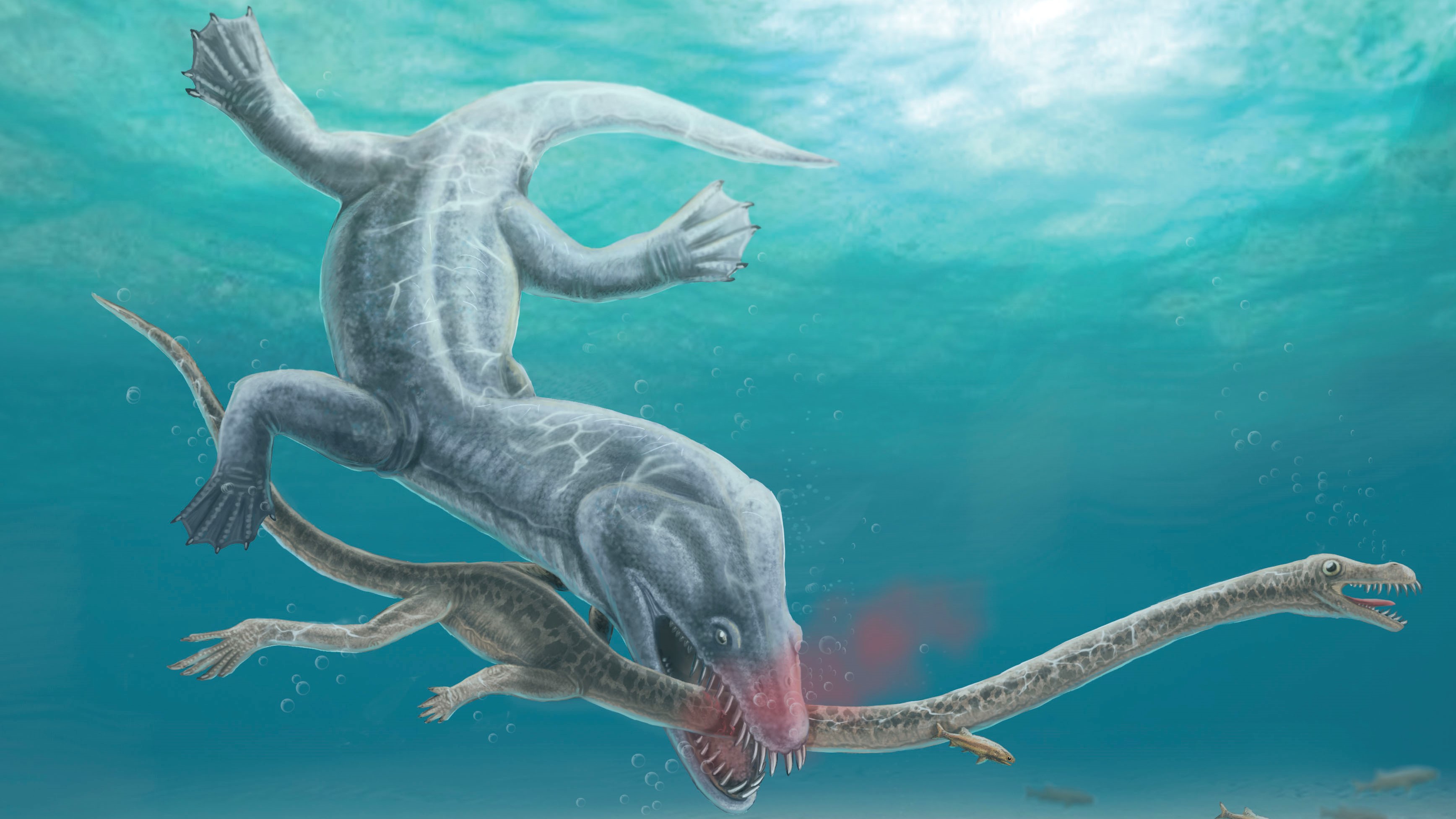

Beheaded in action

A fossil from the Middle Triassic (247 million to 237 million years ago), which was discovered on the border between Italy and Switzerland, showed bone breaks and tooth marks consistent with a brutal beheading. The victim, a giant marine reptile called Tanystropheus hydroides with a neck three times as long as its torso, had its head torn off in one clean bite by an even deadlier creature that likely swooped down from above, experts said.

It's unclear which predator could have killed the 20-foot-long (6 meters) reptile, but researchers narrowed down a list of suspects by measuring the distance between the tooth marks. Potential candidates include the 18-foot-long (5.5 m) ichthyosaur Cymbospondylus buchseri; an enormous reptile measuring up to 23 feet (7 m) long called Nothosaurus giganteus; and Helveticosaurus zollingeri — an enigmatic, 12-foot-long (3.6 m) predator.

Slasher dolphin with jutting teeth

In June, researchers identified a stunningly preserved dolphin skull as a newfound species that lived 25 million years ago during the Oligocene period (34 million to 23 million years ago). The fossil, which was first discovered buried in a cliff face in 1998 and was being held in a museum collection in New Zealand, was recently named Nihohae matakoi, from Maori words meaning "slashing teeth, face sharp."

The skull was around 2 feet (60 cm) long and sported long teeth that stuck out almost horizontally from what would have been the snout. These spade-like teeth were probably unsuited to catching fish, the researchers said, but the creature may have thrashed at its prey to stun it before slurping it up. It's also possible the dolphin's jutting teeth served a sexual or social purpose.

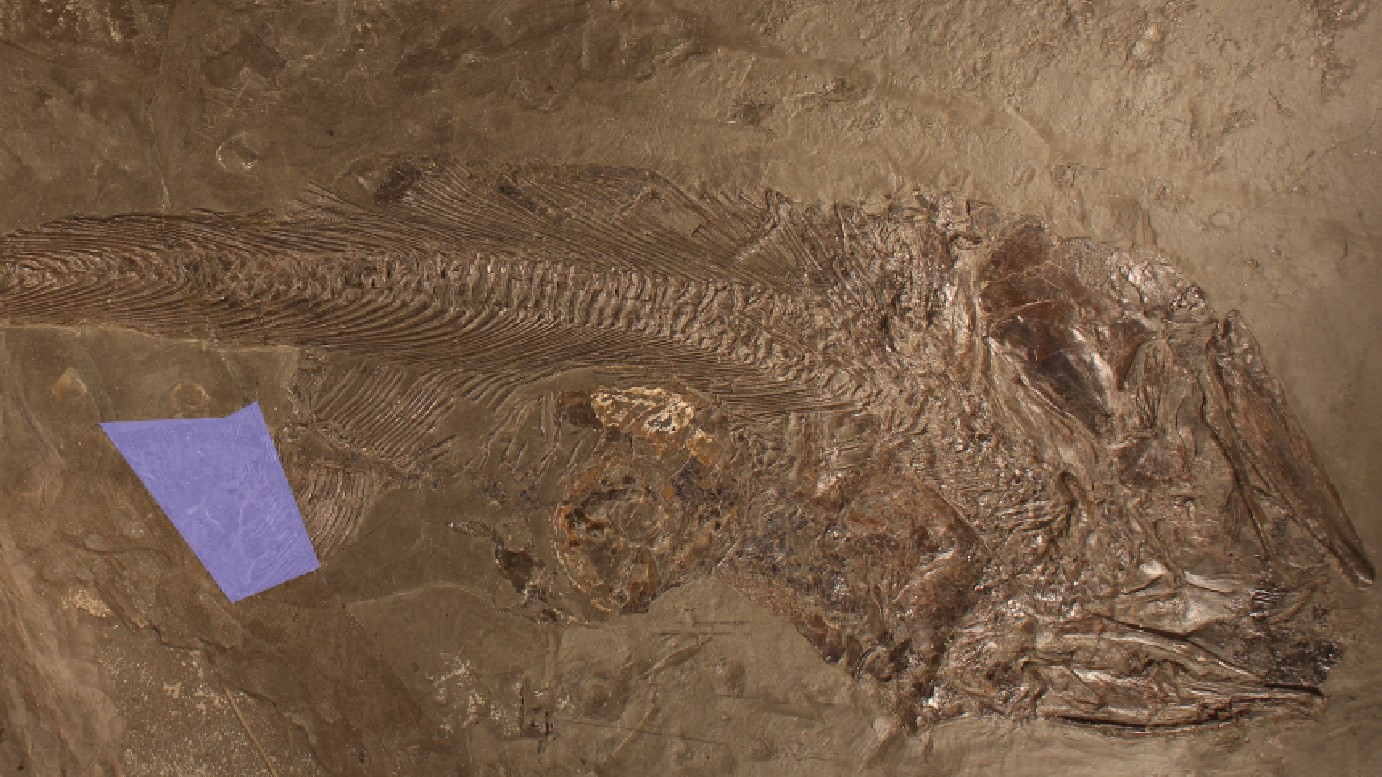

Prehistoric fish's last supper

An intriguing fossil found in a museum drawer captured the moment a prehistoric fish swallowed an ammonite — an extinct marine mollusk — and choked to death on it. The ammonite remained intact inside the fish's body and became imprinted in rocks, lodged up against the predator's spine. The pair likely died together about 180 million years ago, during the Jurassic period (201 million to 145 million years ago).

The fossil was discovered in 1977 near Stuttgart, in southwest Germany, but researchers initially stored it away, as they thought the pairing of the fossilized fish and ammonite was a coincidence. Another look recently revealed the ammonite was inside the fish and likely caused its death due to the mollusk's size — equivalent to a human swallowing a dinner plate.

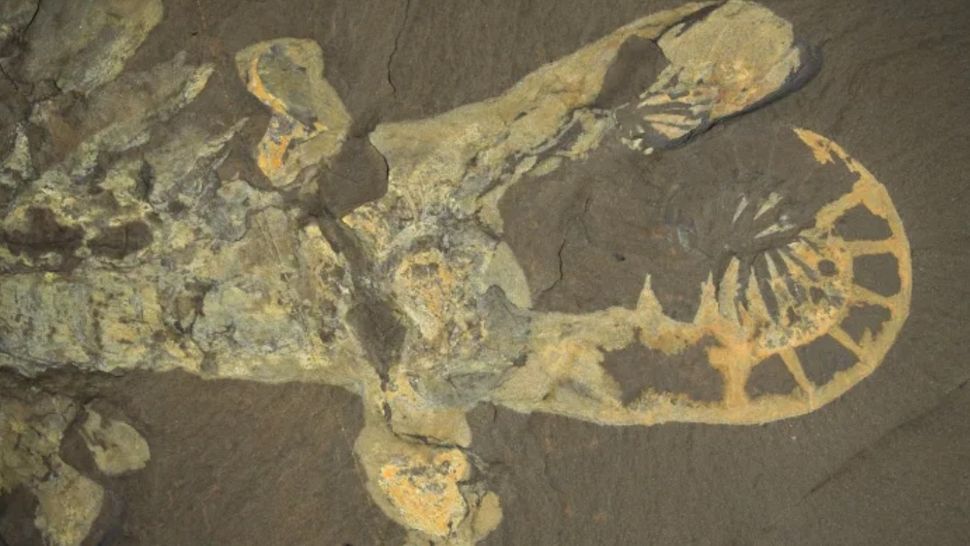

Mysterious golden fossils

Shimmering fossils of marine animals from Germany's Posidonia Shale were long thought to glow gold thanks to a mineral called pyrite, but they turned out to contain very little of it. Instead, researchers traced the fossils' golden glimmer to phosphate minerals with yellow calcite. Unlike pyrite, phosphate minerals need oxygen to form, which revealed new information about the fossilization process in the region.

Fossils from the Posidonia Shale — which include ammonites, bivalves and crustaceans from the Jurassic period — are found in what researchers once thought was a completely oxygen-depleted environment. The discovery of phosphate minerals in the grooves means a burst of oxygen must have reached them at some point, turning the fossils into what looks like gold.

Mystery of prehistoric shrimp's supper solved

A shrimp-like Cambrian critter's choice of food has surprised scientists: It was thought to feed by piercing hard-shelled prey, but it turns out it likely hunted soft-bodied animals instead. In July, computer models of fossils dating to 500 million years ago suggested Anomalocaris canadensis, which was about the size of a house cat and boasted two spiky facial appendages, probably swam like a cuttlefish with its appendages outstretched to pincushion prey.

Contrary to what was previously thought, A. canadensis' appendages probably weren't robust enough to skewer trilobites — extinct marine arthropods with a tough exoskeleton. So the strange creature more likely feasted on squishy animals floating in the water column.

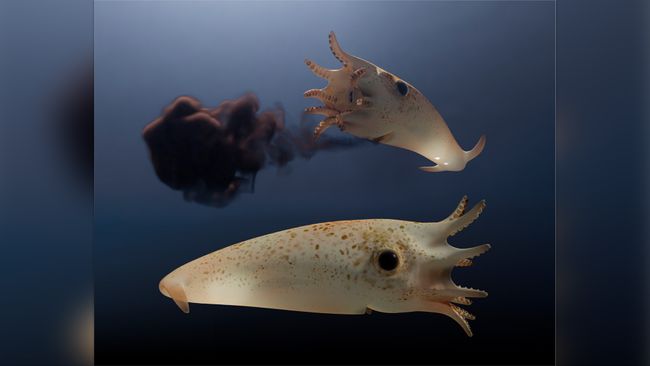

Fleeing vampire with luminous organs

A new analysis of fossils belonging to a group of mostly extinct, octopus-like creatures called vampyromorpha revealed a previously undescribed species with eight arms, sucker attachments like a vampire squid and glow-in-the-dark organs.

The 3.2-inch-long (8 cm), bullet-shaped creature stalked Earth's oceans 165 million years ago and likely snatched prey using its arms. Researchers in France named it Vampyrofugiens atramentum — a combination of the Serbian word for vampire, "vampir," and the Latin word for fleeing, "fugiens" — meaning the fleeing vampire.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.