Nearly 6 million-year-old 'elephant graveyard' unearthed in Florida

Paleontologists have uncovered a graveyard of ancient elephant relatives.

An ancient "elephant graveyard" chock-full of massive bones has been unearthed along what was once a prehistoric river in northern Florida.

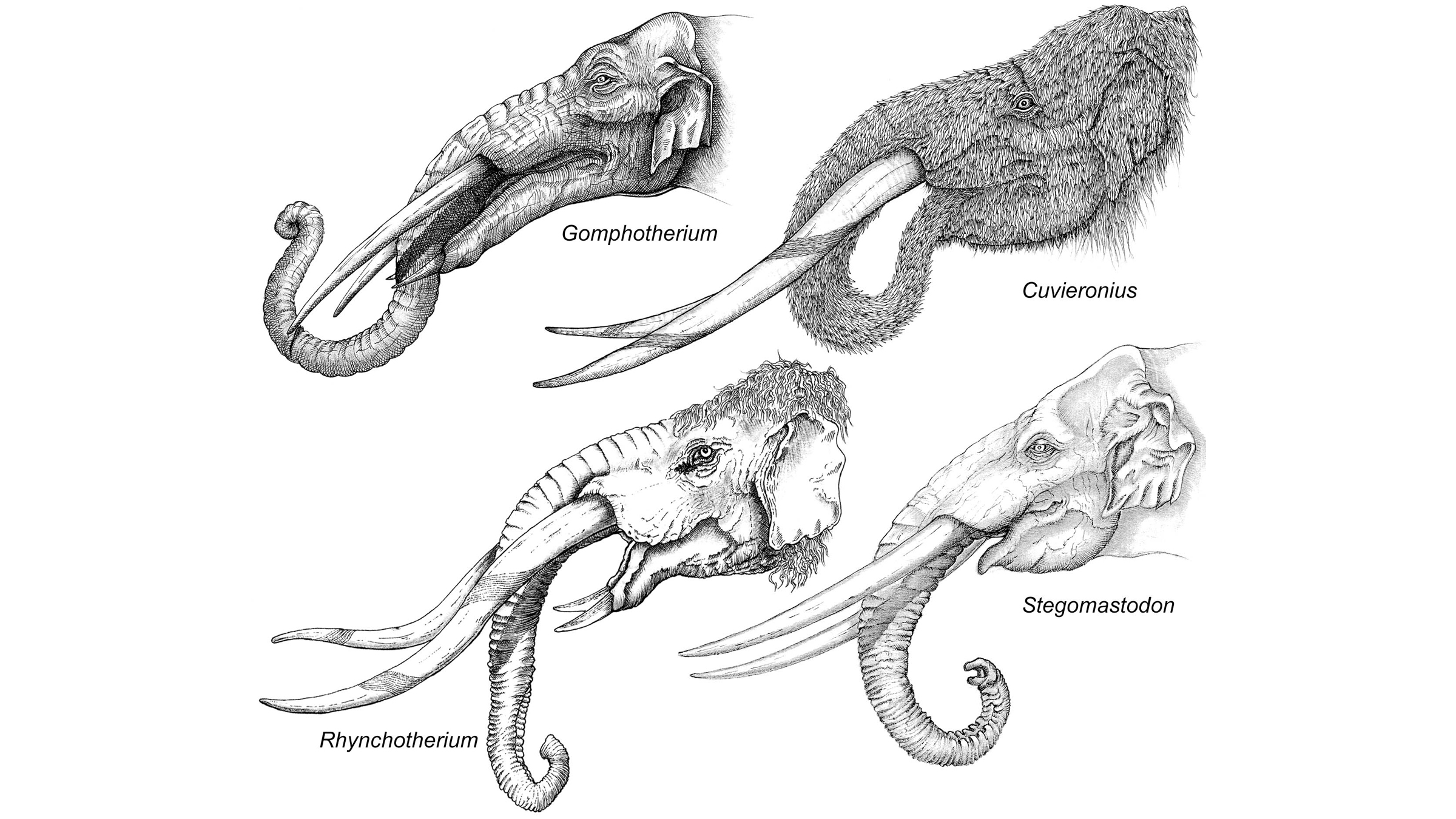

The fossils of these long-extinct beasts belong to gomphotheres — a relative of modern elephants — and date to about 5.5 million years ago, during the Miocene epoch.

"It was very exciting because this gave us an opportunity to not only see what an adult [gomphothere] would have looked like, but also to very carefully document each and every bone in its skeleton," said Jonathan Bloch, a curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Florida Museum of Natural History who co-led the excavation. "That's exciting from a scientific perspective if you're trying to understand the anatomy of these animals and something about their biology and evolution," Bloch told Live Science.

Researchers discovered the trove of gomphothere bones at the site, a large-scale excavation area near Gainesville known as the Montbrook Site, in 2022. Although excavators had unearthed some gomphothere bones there before, the team was surprised when a volunteer found the remains of an especially large individual.

"I started coming upon one after another of toe and ankle bones," Dean Warner, a retired chemistry teacher and Montbrook volunteer, said in a statement. "As I continued to dig, what turned out to be the ulna and radius [long arm bones] started to be uncovered."

Related: The most surprising elephant relatives on Earth

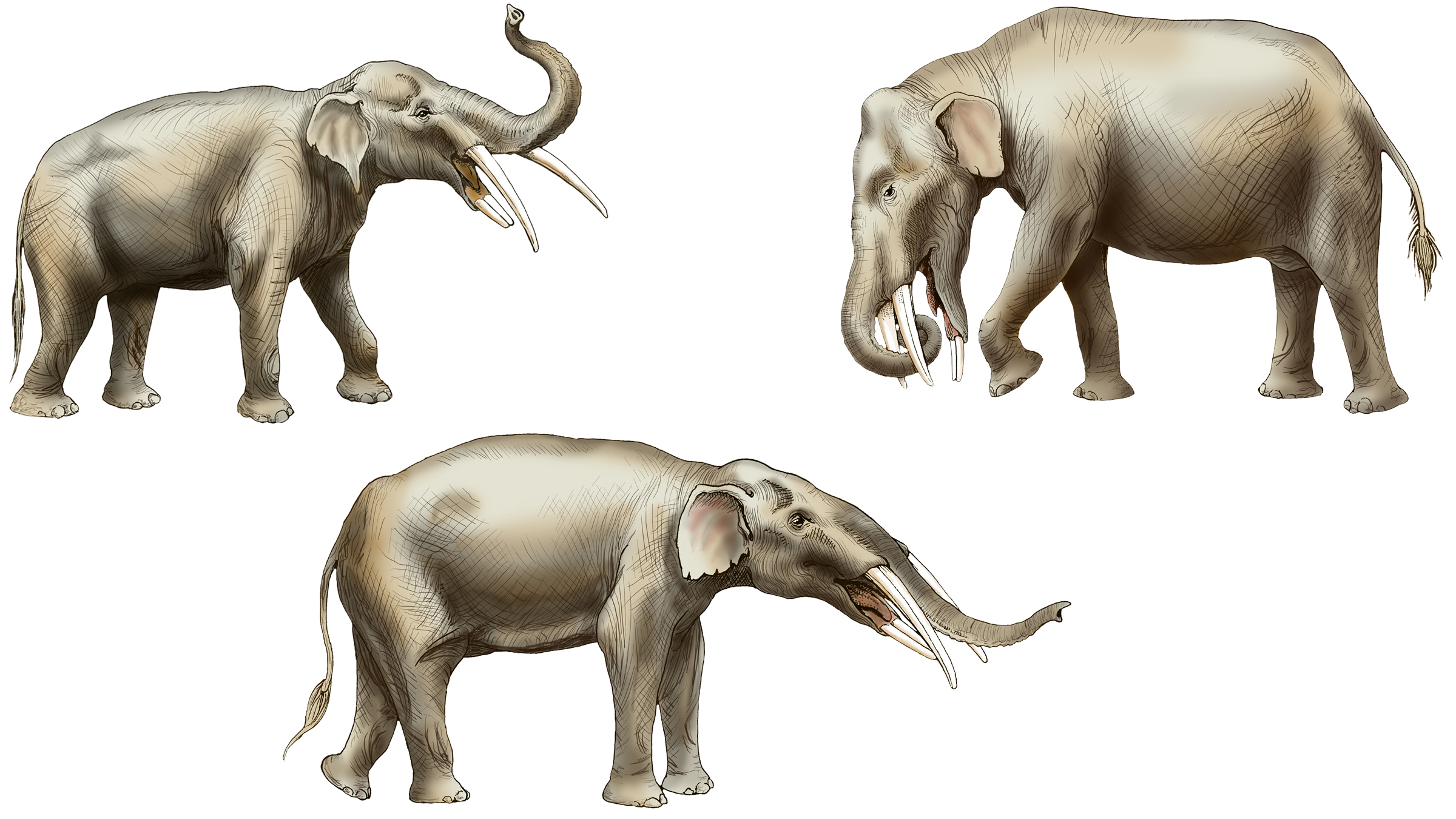

Eventually, the team excavated entire skeletons from one adult and at least seven juvenile gomphotheres. The adult measures 8 feet (2.4 meters) tall to the shoulders, the scientists estimated, while its skull and tusks are more than 9 feet (2.7 m) long, which is roughly the same size as a modern African elephant (Loxodonta africana) — a remarkable size that sets a local record for largest gomphothere.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Not only were the bones much larger than any of the other individuals that we've seen, but they were actually in place as if the animal had just laid down and died," Bloch said.

The animals likely died hundreds of years apart rather than all at once. The researchers believe the adult drowned at this location, while the other animals were likely swept up by the water after dying and accumulated at a bend in the river. Bloch called the pile-up a "bonejam," similar to when too many loose logs clog up a river to create a logjam.

Species in the gomphotheres' family are typically differentiated by their tusk shape and body size. The tusks of the ancient Montbrook beasts have a unique enamel banding, which means these species are part of the genus Rhynchotherium, the researchers said. Millions of years ago, these elephant relatives once thrived in open savannas throughout Africa, Eurasia and the Americas. However, grasslands gradually started to replace savannas in these areas due to cooling temperatures beginning around 14 million years ago — and competition over limited resources following the arrival of mammoths and elephants eventually drove gomphotheres to extinction about 1.6 million years ago, a 2020 study in the journal Paleobiology found.

The new discovery will help researchers better understand the lives of these ancient proboscideans and the environments they lived in, according to the researchers. Eventually, the public will be able to see the largest specimen on display; Bloch and his team are planning to assemble the fossils from the adult gomphothere and place it alongside the massive mammoth and mastodon skeletons currently at the Florida Museum of Natural History.

"There's so much we can learn from these things and we're excited to do it in future," Bloch said.

Kiley Price is a former Live Science staff writer based in New York City. Her work has appeared in National Geographic, Slate, Mongabay and more. She holds a bachelor's degree from Wake Forest University, where she studied biology and journalism, and has a master's degree from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.